Dreaming up a perfect solution for the Iraqi crisis

Over the past couple of months, Iraq has lurched from one crisis to another. The most recent problems began in early June, when the Islamic State (IS) militant group wrested control of swathes of the country from the Iraqi government.

Earlier this month, those same extremists - from the group formerly known as the Islamic State, or IS - moved into northern Iraq and confronted Iraq’s Kurdish community, a group that has so far, stayed out of what had been seen mostly as an intra-Arab conflict that pits Sunni Muslims against Shiite Muslims.

It was an alarming sign that the extremists planned to move on to threaten the rest of Iraq; it also resulted in a major humanitarian crisis as locals in IS’ path fled without food, water or shelter into the wilderness and deadly 40 Celcius-plus Iraqi summer heat. As a result, lat week, the US returned to Iraq with both military and humanitarian aid.

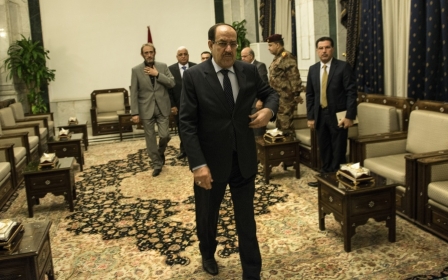

Over the past few days, the focus has shifted back to Baghdad, as Iraqi politicians try to confirm their next prime minister. The current, and most likely soon-to-be-former prime minister, Nuri al-Maliki, doesn’t want to leave his job without a fight. There has been worrying talk of a potential coup, with rumours of military intervention and threats against opposing politicians.

As one wit put it: What’s next for Iraq? A plague of locusts?

It’s hard to know whether and when the locusts will arrive. But one thing is clear: most ordinary Iraqis don’t want to go back to the bad old days between 2006 and 2008, when the country saw a state of civil war, as Iraq’s two major sects fought one another after decades of oppression and manipulation by Saddam Hussein.

A potential solution

So what is the solution? What if ordinary Iraqis could wake up tomorrow and live out their dream scenario – one that would allow them and their loved ones a peaceful, prosperous life in their own country? What would it entail?

It might go a little like this: first, Prime Minister Maliki will get on a plane headed for the Bahamas together with members of his family. He will do this to avoid being arrested for corruption, or any other crime, after having stepped aside in a dignified manner, allowing the country’s newly nominated leader to take his place.

The new prime minister – looking very likely to be Shiite politician, Haider al-Abadi - will then do his utmost not to repeat Maliki’s mistakes. He will overcome doubts about his potential to be a puppet of Maliki and his party. He will do his best to form a truly inclusive cabinet, giving the most important positions in the Iraqi government to those who best suit them, regardless of which sect of Islam they belong to, into which ethnicity they were born, or how much money and how many favours they offer him for the job.

Once that’s sorted, Abadi and his new government will also do their best to resolve conflicts between the different sectors of Iraqi society, they will pay the money they owe to Iraqi Kurdistan and other provinces and they will work hard on debating, then passing outstanding legislation that has the potential to resolve some of Iraq’s long standing political grievances.

Over the past eight years he has been in power, Maliki, also a Shiite Muslim, has managed to avoid doing much of any of that. Instead, he has centralised power in Baghdad, and more specifically, among his own supporters and family. He has avoided passing important laws, ensured that the parliament is powerless, broken all kinds of rules and bent the constitution and the courts to his own ends; although it has taken time, he has basically managed to establish what has accurately been described as an informal dictatorship.

Before Mosul, After Mosul

Iraqis now refer to current events as “before Mosul” and “after Mosul,” Mosul being the first city of which IS took control around 10 June. Before Mosul, there were anti-government protests in this area and other areas for almost a full year. The protestors were mostly Sunni Muslims in Sunni Muslim-majority areas, who said that they were being treated unfairly by the Maliki government as a result of all of the above.

By unfairly, they meant everything from being denied jobs because of their religion. In an oil dependent country where the government provides most of the jobs, this is a big problem. They also complained of being arrested, beaten and harassed by Iraqi security forces, which, during Maliki’s rule, had evolved to employ almost only Shiite Muslims.

All of the above created an atmosphere that extremists have been able to exploit. For example, in April 2013, the mostly-peaceful demonstrations in the northern town of Hawija were dispersed violently by government forces; killing around 20 people.

Hawija is now one of the only parts of Kirkuk province completely controlled by IS. Although we don’t know how the people of Hawija felt about IS when they first arrived, riding in on armoured vehicles and waving their black flags, it may well have been similar to what happened in Mosul.

Locals cheered the arrival of those they described as “Sunni rebels,” who freed imprisoned demonstrators and opened roads that had long been closed by the Shiite-dominated Iraqi army. When you’re forced to travel four blocks out of your way every day, through two intimidating checkpoints, just to buy some bread, this matters. When your cousin was arrested on trumped up charges of terrorism, just because she protested against the government, it matters. So of course you’re grateful to those who cleared the road and freed your cousin.

“At least we are no longer being harassed by the Iraqi army,” Mosul locals all said when asked why they were so happy.

Back in Baghdad, the new prime minister would then call on all 328 Iraqi MPs to work hard toward the implementation of a law that was passed in the middle of 2013. Law 21, or the Provincial Powers Law, gives more power to local authorities and takes it away from the central government. It also gives the provinces more financial independence, especially when it comes to natural resources like oil and gas. But it avoids breaking the country up.

Once this law is properly enacted, ordinary Iraqis will find that if a province in the west of Iraq – Anbar, for example – is mainly populated by Sunni Muslims, a population that voted for a mainly Sunni Muslim provincial administration, then those provincial administrators would be able to make many important decisions independently of Baghdad, and, hopefully, in the best interests of their Sunni Muslim constituents.

The leaders of Sunni Muslim tribes in areas that are currently controlled by IS will like this. And they would eventually decide that making their own decisions is better than being part of the fantasy kingdom created by a cruel and violent group like IS.

IS recently renamed themselves simply the Islamic State, or IS, because they decided they had a “country” and a “king”.

Unlike many other places in the Middle East, IS group doesn’t have a long standing political or historical problem that can be solved with patient negotiations. Their goal appears to be purely ideological - or theological, if you will. Basically they will kill, kidnap, torture, crucify, sell or, if you’re particularly unlucky, bury alive, anyone who doesn’t agree with their version of Islam. And it doesn’t matter if you’re Sunni, Shiite, Christian, Yazidi, Arab, European, black, brown or green - even though as many scholars of Islam have already pointed out, the IS’s version of reality hasn’t got much to do with contemporary Islam and possibly even less to do with the Islamic kingdoms, or caliphates, that existed before and after the 17th century.

Although this is supposed to be a nice dream, what comes next will be nightmarish. Those in Iraq who may originally have welcomed the extremists but who now no longer believe in the IS group’s fairy tale religion, won’t be able to extract themselves without a fight. According to IS fighters, anyone who swears fealty to the IS’ leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, is in his gang for life.

Much has been made of IS’ lightning-fast takeover of territory in Iraq. And if you just read headlines or watched Fox News, you would think that the group was akin to an invincible bunch of storm troopers charging around Iraq, led by Darth Vader.

As one analyst pointed out this week, a lot of people have been talking about the fact that IS fighters have made surprising gains. But actually, part of the reason they made those gains wasn’t that they are some vastly, superior force with God and Darth on their side. Recent events may well have had more to do with lack of experience, tacticians and sophisticated weaponry and ammunition on the part of their opponents.

To further debunk the “invincible IS” story, it is obvious that they could not have done any of this on their own. The group had been operating inside Mosul, in one incarnation or another, for years before they arrived there on 6 June. Mosul was a well-known base for Sunni Muslim extremists, and up until recently, they acted more like a terrorist mafia - extorting money, kidnapping and killing - than a conquering army. What went on in Mosul funded a lot of what went on elsewhere, like in Syria.

Also worth bearing in mind: Mosul is a city with over two million inhabitants. The Iraqi army and police had an estimated 35,000 troops in Mosul before the city was attacked. In early June, IS was thought to have no more than 6,000 members in Iraq and Syria; now they possibly have 10,000. Reports also suggest that no more than a thousand fighters actually “conquered” the city.

The point to those numbers being, that IS could not have “conquered” Mosul by itself. They had plenty of friends and allies inside the city before they even got there. It remains difficult for them to seize power in areas where they don’t have support. For example, in Iraqi Kurdistan or Baghdad. Even if, by dint of superior military tactics, they managed to enter areas without a Shiite Muslim or Kurdish majority and behead a few people, as they are wont to do, it would be extremely tough for them to maintain control of those areas over time.

For the same reasons, it would be a bad idea for Iraqi Kurdistan’s military or the Iraqi army to enter further into the Sunni Muslim areas of Mosul.

IS's local “frenemies”

That also means that if the IS group’s local “frenemies” decide to abandon them, they’ll be in trouble. Recent history tells us that, although some of Iraq’s tribes may be socially and religiously conservative, a group like the Islamic State - who force unmarried women to wear white veils, conscript children to their cause, whip men for smoking cigarettes and, perhaps most importantly for ordinary Iraqis, can’t get the electricity going or provide employment - cannot hold onto power for long.

The so-called Awakening Movement, or Sahwa, funded by the US to fight al-Qaeda when Iraq’s sectarian conflict was at its worst, was proof that if local Sunni Muslims don’t support local Sunni Muslim extremist groups, the latter find it a lot harder to go about their murderous business.

There have already been signs that dissatisfaction is growing and that locals will eventually act against IS, if they go too far. Examples include popular protests against the way that IS levelled a number of landmarks, religious and historic, in Mosul, as well as a handful of assassinations. In Kirkuk, where IS shares power with around eight other groups, including tribal militias and secular groups, there have been attempts by some tribes to enact their own, more moderate policies. For all their allegiance-pledging, in Anbar, IS fighters had to ask local tribes if they could enter certain cities.

In this optimistic dream of ordinary Iraqis, IS will just alienate more and more of the local population – a population accustomed to conflict, where most households own at least one gun – with their evil ways.

Moderate Sunnis will see they have more power over their own destinies – and more electricity and jobs and less Sharia law - if they support the government in Baghdad. And so the situation will change: As a result of the withdrawal of popular support, the extremists’ power will eventually be much diminished. They are forced to pull back – possibly just to Mosul – a city they have total control over - or all the way back to Raqqa in Syria.

This would also mean that militias made up mainly of Shiite Muslims - that have been “defending” Baghdad and other areas with majority Shiite Muslim populations, as well as, reports suggest, terrorising and killing Sunni Muslims - would put their guns down and go home to their families.

What of the US? They left some time ago, having fulfilled their mandate – protecting foreigners inside Iraqi Kurdistan, bringing aid to the displaced and desperate and helping the under-resourced Iraqi Kurdish fighters make gains against IS fighters.

The US decision to intervene was the right one, made at the right time. If they had supported Maliki against IS earlier on, they would only have deepened sectarian divides; it would have looked as though the US was on the side of Iraq’s Shiites, and not the Sunnis.

But having provided air support for Iraqi Kurdish forces in northern Iraq, they have avoided that. Comparatively the most peaceful and prosperous part of Iraq up until last week, the semi-autonomous region was already hosting over 1 million people sheltering from fighting in the rest of Iraq and from Syria, not to mention providing a secure base for most of the foreigners doing business in Iraq today, as well as a number of Western consulates. Iraqi Kurdish politics are far from saintly, there’s plenty of corruption and infighting there too, but at least they (mostly) seemed to be doing their non-denominational best.

Having helped to rescue the thousands of members of the Yazidi ethno-religious group and tipped the fight against the IS group in the right direction, the US is able to pull back their fighter jets, leaving only their usual contingent of advisers, diplomats and accompanying security staff on the ground. All other nations interfering in Iraq, whether for military or humanitarian purposes, also go back their usual positions of “influencing,” basically leaving the Iraqis to get on with it.

And so the dream ends. An inclusive, well-intentioned Iraqi government has been formed. Iraq’s different sectarian and ethnic groups resolve some of their most pressing differences and promise to work on the others. A local uprising of their unwilling supporters forces the extremists to dismantle their fantasy kingdom and pull back. And while they’ve lost a lot in the past decade, the Iraqi people will look forward to a future where they are finally able to live in peace, their incomes bolstered by the wealth of oil their nation possesses.

And now? It’s time to wake up.

- Cathrin Schaer is the Editor-in-Chief of the Iraqi current affairs website, NIQASH.org. The site publishes features and commentary in three languages – Arabic, Kurdish and English - by Iraqi journalists and writers, from right around the country.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo credit: A Peshmerga is seen following Peshmerga forces' seizure of Makhmur by repelling Islamic State (AA)

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.