The military complex: Egyptians and the Stockholm Syndrome

At the end of The Godfather, Michael Corleone, having reached the zenith of an American Mafia family is asked by his grief-stricken sister why he killed her husband.

After his screaming sister leaves the room without an answer, his wife, Kay, asks again. He shirks her off, saying it is none of her business. But then he reconsiders.

“This one time, I’ll let you ask me about my affairs,” he says.“Is it true?” she asks.

Decisive and cold-blooded, he says, “No.”

They hug and she suggests they both need a drink. As she mixes pours the drink in the next room, his henchmen enters, having just murdered several of his opponents, kisses his hand and calls him “Don Corleone”.

Like Michael Corleone, the Egyptian army, as the supreme political entity in Egypt since 1952, has been lying to Egyptians. They lied in 1967, during the most devastating defeat in Egyptian history, and do the same now via an Abdel Fattah al-Sisi presidency.

Just like Corleone’s wife, Egyptians know they are being lied to but continue in an abusive relationship. To understand Egypt’s present situation, we must understand why.

From victory to Naksa in two days

On 5 June 1967, Egyptians thought they had touched the clouds only to crash into the desert of lies. “Egyptian planes fly deep into Tel Aviv skies,” Egyptians papers reported.

Ahmed Said, a very popular radio host at the time, went on air, at the war’s outset, proclaiming an astonishing Egyptian victory with 80, then a 100, and then a thousand Israeli planes destroyed!

Gamal Abdel Nasser, a champion of the poor to many millions and a military dictator to many others, was responsible for the biggest military blow in Egyptian history.

The specific Egyptian brand of the Stockholm Syndrome is an unending love affair with military heroes, military ethos and the military institution

Yet here we are, weeks away from the 50th anniversary of the Naksa (or "The Setback" as the Six Day War came to be known in Egyptian lore) and the military complex wields incomparable power in the Egyptian realm.

And it is here, to understand why most Egyptians remain committed to an insidious mixture of dictatorship and military rule, we must look to the Stockholm Syndrome.

Stockholm Syndrome

To be kidnapped and develop a highly atypical sympathetic and positive relationship with the kidnapper is the epitome of Stockholm Syndrome.

The most famous of these cases occurred in 1974, when Patty Hearst, an American socialite, was kidnapped by revolutionary militants. Hearst not only sympathised with her kidnappers, but joined them in an armed robbery which led to her arrest.

“Egyptians aren’t ready for democracy”, “Egyptians only know the stick” or “Democracy can never work here” are not ideas monopolised by the oppressors who have ruled Egyptians but, painfully, are used by the populous itself.

Question a hundred Egyptians and there won’t be one among them who hasn’t heard a phrase synonymous with those sentiments spoken by a friend, a colleague or a family member.

It is not as irrational as it sounds when viewed through the Stockholm Syndrome’s prism. And Nasser, the Egyptian president, who led the Free Officers in a 1952 rebellion against Britain, is a prime example of that (not so) irrational national gaze.

Kidnapping a nation

Take "a man of the people" armed with oratory panache, mix in a ready-made villain like the British who ruled Egypt from 1882-1952, sprinkle healthy doses of ignorance, inject nationalism and a kidnapping of a nation is reality.

The thing about heroism is this: historically, it has often given birth to strongmen.

A moment of democratic potential was snuffed out by a power-hungry, military ruling elite

In 1954, less than two years after the switch in power, autocracy’s screenplay was in full effect: the parliament was gone and political parties were history. Having just gained its freedom, Egypt lost it again.

Not everyone was blinded. There was Mohamed Naguib, Egypt’s first president after the 1952 revolution, who led the Free Officers and provided the young neophytes with political cover and, more importantly, understood the danger.

But when he called for the army’s return to the barracks, it was a face-off with a more politically cynical Nasser, and Naguib lost. A moment of democratic potential was snuffed out by a power-hungry, military ruling elite.

Despite his iron-fisted presidency, Nasser managed some important victories. There was the nationalisation of the Suez Canal and agrarian reforms that saw land owned by the Egyptian autocracy handed over to farmers who became a strong power base for the populist. Making education free certainly did not hurt the man’s appeal either.

But also under his rule, thousands were tortured in prison, state censors were encamped in every newspaper, radio station and TV station, and walls "had ears". And so, using the same tactics Sisi would employ decades later, the opposition was demolished.

Nonetheless, tens of millions threw their support to Nasser, blinded by this highly charismatic hero-cum-dictator.

This should have surprised no one. No adult knew what democracy smelled, tasted and felt like - all Egyptians had known was the whip, stretching back for centuries.

Even when the Egyptian air force was decimated before takeoff, when thousands of soldiers were taken hostage in an unprecedented national humiliation, when Nasser was on national TV resigning, millions of Egyptians, in an act of political masochism, rushed to the streets to scream for his return.

Though many analysts believe the political establishment triggered those demonstrations, the Egyptian proverb applied: “The cat loves none but its master.”

Cult of the hero

During the 1967 war, 11,500 died, 10,000 prisoners were taken, yet Gamal Abdel Nasser is still a man loved by millions. His grave site remains popular.

And that is because central to the specific Egyptian brand of the Stockholm Syndrome is an unending love affair with military heroes, military ethos and the military institution that embodies all that precedes it.

Flip the switch to January 2011, 40 years after Nasser’s death in 1970, and a similar scenario unfolds yet again. Egyptians subjected to a strategic animal’s autocracy for 30 years rise only to be counterattacked by a wolf of an army in sheep’s clothing.

No wars, just lies

Days after a historic revolution, the army starts to torture revolutionaries at the Egyptian museum, steps away from revolution’s birthplace in Tahrir. “The torture took four hours,” a revolutionary singer, Ramy Essam, told CNN about how army officers beat him to a pulp.

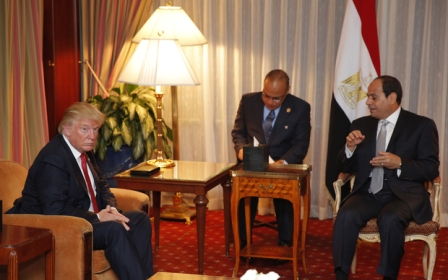

At precisely that moment, mass hypnosis ruled and the national chant was “the army and the people are one hand”. Sisi himself, a senior intelligence figure and a SCAF member, met with leading revolutionaries, a now infamous picture showed.

Trust given to the military establishment spoke volumes about the naivete and historical illiteracy of youthful revolutionaries who played dominoes with chess grandmasters and lost.

These army men - and Sisi is a prime example - believe deception is justified within warfare, only there are no wars, just lies. Sisi’s announcement of his presidential candidacy was itself a lie as he had promised not to run for president.

Lying again, he declared: “It wasn't the army or political forces who ousted the last two regimes; it was you the people.” As was the case with both the revolution and the coup, nothing happens in Egypt without the army’s engineering and faciliation - or at the very least, its stamp of approval.

The leadership insists on bucking history and leading a war against guerillas with a conventional army

Doubt the army contorts facts? Examine the events of the last three years in northern Sinai, read the government press echoing the army spokesperson verbatim, and then compare those accounts with the limited independent or Western press.

These aren’t differences of opinion, but systematic and intentional lies to cover up a failing war against a cohesive enemy who is killing Egyptian boys at much higher rates than the army leadership will admit. It is a leadership that insists on bucking history and leading a war against guerillas with a conventional army.

This mismatch has, invariably and historically, turned into disaster. It would take two articles, not one, to speak of rising civilian casualties. A recent Carnegie Endowment report crystalises the unfolding tragedy: “Egypt’s increasingly heavy-handed tactics in Sinai have led to a dramatic rise in civilian casualties that is turning more residents against the military."

Though the lion’s share of the Egyptian army are brave young men only interested in defending a homeland in desperate need of defence, the same cannot be said for those who formulate its policies. Are Egyptians guilty of collusion by silence? I would scream yes, but qualify that since it is a silence born of Stockholm Syndrome parentage.

Don Sisi likes to have his hands kissed just like Don Corleone. And with those kisses Egyptians will help recreate a replica of 1967, 50 years later. In fact, we’re already in 1967 2.0. But that’s for our next conversation.

- Amr Khalifa is a freelance journalist and analyst recently published in Ahram Online, Mada Masr, The New Arab, Muftah and Daily News Egypt. You can follow him on Twitter@cairo67unedited.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Egyptian mourners waving the national flag and a portrait of then-Egyptian Defense Minister and Military Chief General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, during the funeral of Giza security chief Nabil Farrag in the district of Giza, on the outskirts of Cairo, on 20 September 2013 (AFP)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.