Dutch elections: Rotterdam, a diverse and divided cradle of populism

Tucked away in a quiet square in central Rotterdam is the grey bust of a bald man, one arm outstretched, atop a tall plinth with a Latin inscription: “Guard freedom of speech.”

The statue is of Pim Fortuyn, the firebrand Dutch sociologist and politician who achieved meteoric success in this modern, multicultural port city – and throughout the Netherlands – before being assassinated by an animal rights activist in 2002. He had been known for asking the questions nobody else dared to – including whether Islam could ever be compatible with mainstream Dutch culture.

Over a decade since his assassination, the same anxieties and xenophobia that fuelled his rise are still rife in the ethnically diverse city that fed his success. One man, seen by many as a direct ideological descendant of Fortuyn, is hoping that tense atmosphere will propel him to victory in the Dutch general elections next week – that man is Geert Wilders, and support for him is widespread here.

"There is one person for me, and that is Wilders"

"We have a lot of trouble with immigrants, and I don't like that," says Gerard Fritestra, a 62-year-old who installs gambling machines in pubs and coffee shops. "When immigrants work it’s good, but most of them don't have work and just live on the streets.

"There is one person for me, and that is Wilders," he adds, with a note of pride.

Freya Reyda, a 22-year-old who volunteers at food banks in immigrant-heavy south Rotterdam, says she often hears such remarks from clients, particularly white locals.

"The old Rotterdammers really hate those people," she says during a cigarette break outside one food bank, in a dreary square surrounded by closed shops and council flats in the predominantly white, working-class neighbourhood of Ijsselmonde. "I hear, 'Oh the f***ing foreigners, go back' ... It's really negative stuff."

Wilders has also won support from other, perhaps less likely, quarters. Aylin Rangi is a 20-year-old student in Rotterdam. Her Iranian parents, once immigrants themselves, support his right-wing populist Freedom Party (PVV), and Rangi, who was born in the Netherlands, now intends to cast her first vote in the same way.

Rangi puts her choice down to the strict border controls Wilders promises to put in place.

“And the fact that he is against criminality among foreigners, or as they say in Dutch 'tuig' [scum] – that’s something I agree with,” she adds.

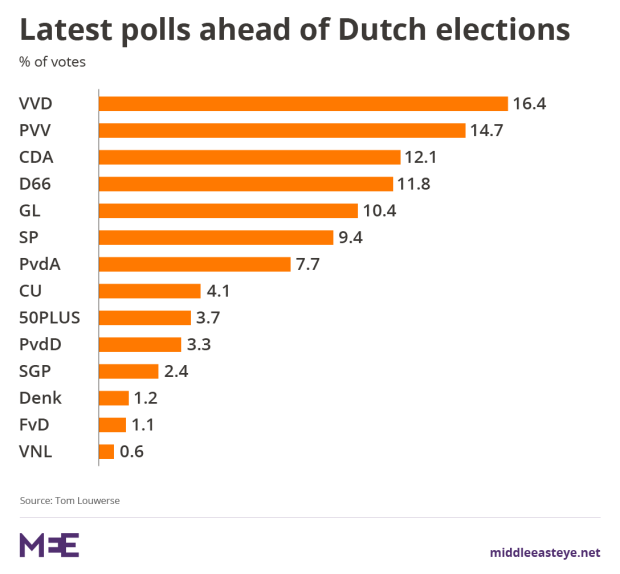

But despite the potency of his anti-immigrant message for some, the latest polls show his Freedom Party losing support, with the incumbent VVD party starting to overtake.

Some researchers speculate that the two parties will win 20 and 24 seats respectively in the 150-seat parliament. A slew of other groups are expected to get upwards of a dozen seats each, making this one of the most fractured Dutch elections in years – an outlook that is reflected on the streets and waterways of Rotterdam.

"Our members in the port sector are just regular people like in the rest of the Netherlands," says Niek Stam, national secretary for port workers’ union, FNV Havens. "So if the polls say 20 percent of people will vote for Wilders, then 20 percent of our members will vote for Wilders, and so on."

He says port workers in Rotterdam, the largest port in Europe, are "fed up" as they struggle to deal with tax disadvantages, a rising pension age, cheap labour flooding in from Europe and elsewhere - and the creeping robotisation of their jobs.

"All these things make people worried, unhappy, afraid," he says. "And if the regular political parties don't take action on that for several years, then people will vote for parties of action."

This goes some way to explaining why the parties in government, the Labour Party and the VVD, have been haemorrhaging support in recent years, part of a global trend of discontent with establishment politics that is reflected across Rotterdam.

At a cosy cafe in the north, home to the city's wealthier neighbourhoods, 63-year-old Barbara Witlox explains why she plans to vote for GroenLinks, the fringe green party.

"I think they want to reunite people," she says over a cappuccino. "I hate the tone of Wilders and [Prime Minister Mark] Rutte ... the leaders of the other parties actually listen to each other, they want to bring people together instead of separate them."

Witlox, a speech therapist, volunteers her free time to teach Dutch to refugees. She knows there are social issues that need to be addressed, but remains optimistic.

"I think in Rotterdam a lot of people support the Freedom Party because there are many immigrants ... but most Dutch people want to be together, not apart."

One of the parties campaigning for more "togetherness" is Denk, a diverse, pro-immigrant party founded by two Turkish breakaways from the Labour Party in 2014. They have proven particularly popular among Rotterdam's significant Muslim community, which accounts for nearly 20 percent of the city's residents.

"Denk is not just for Muslims, not just for the left or the right, but for everyone," says supporter Mohammad Bellaziz, a 42-year-old teacher and imam at the Essalam (Peace) Mosque, Rotterdam's largest.

Sipping sickly sweet tea and eating cake in between giving Koran lessons to youngsters, Bellaziz shrugs off Wilders' pledge to “de-Islamicise” the Netherlands.

"If he's going to burn down the mosques I will just pray at home," he says. And if he bans the Quran, another of the Freedom Party leader's controversial promises, "I’ve memorised it, so it's no problem for me."

Bellaziz hasn’t heard of increased discrimination or anxiety related to the election amongst the local Moroccan community, which makes up nearly seven percent of Rotterdam's 630,000 strong population. But at a low-key mosque for Muslim converts in the city's north, it was a different story.

"There's been a lot of Islamophobia," says Samira Sabir, a 25-year-old Dutch-Moroccan lawyer and board member at the Centrum De Middenweg (Middle Way Centre) mosque. "Some women don't want to come in the evening because they are scared of travelling at night in their hijab."

Sabir is worried by Wilders’s rising popularity.

"It's a sign of a sick community, people thinking the way he does,” she says.

One of De Middenweg's attendees is Huda Abu Leil, a 22-year-old social work student who plans to vote for the left-wing Socialist Party. She is dismissive of Wilders as a political player, but admits that the atmosphere in Rotterdam had become difficult for Muslims after a string of attacks across Europe over the past year.

"I'm tired of telling people that it's not my Islam, people asking why I wear the hijab," she says as she picks at a plate of vegetables, part of a women's session on healthy eating. "I’ve never felt that here before."

The growing hostility towards Muslims in the city is even felt by those who aren't religious, but who look as if they might be.

"The mood changes when I step into an elevator or a shop, or just when I walk along the street," says Ben, a 41-year-old who is originally from Sierra Leone and sports a large beard. "In the past couple of years it's (gotten) worse."

Ben is planning to vote for Artikel 1, a spin-off from Denk that campaigns on a ticket of equality. Standing beneath the monument to Fortuyn in central Rotterdam, Ben says the murdered politician, and his successor Wilders, spoke some "hard truths" about Dutch society.

"But how do you deal with it?" he asks. "That's where I think people need to create a bit more understanding."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].