Explained: The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam

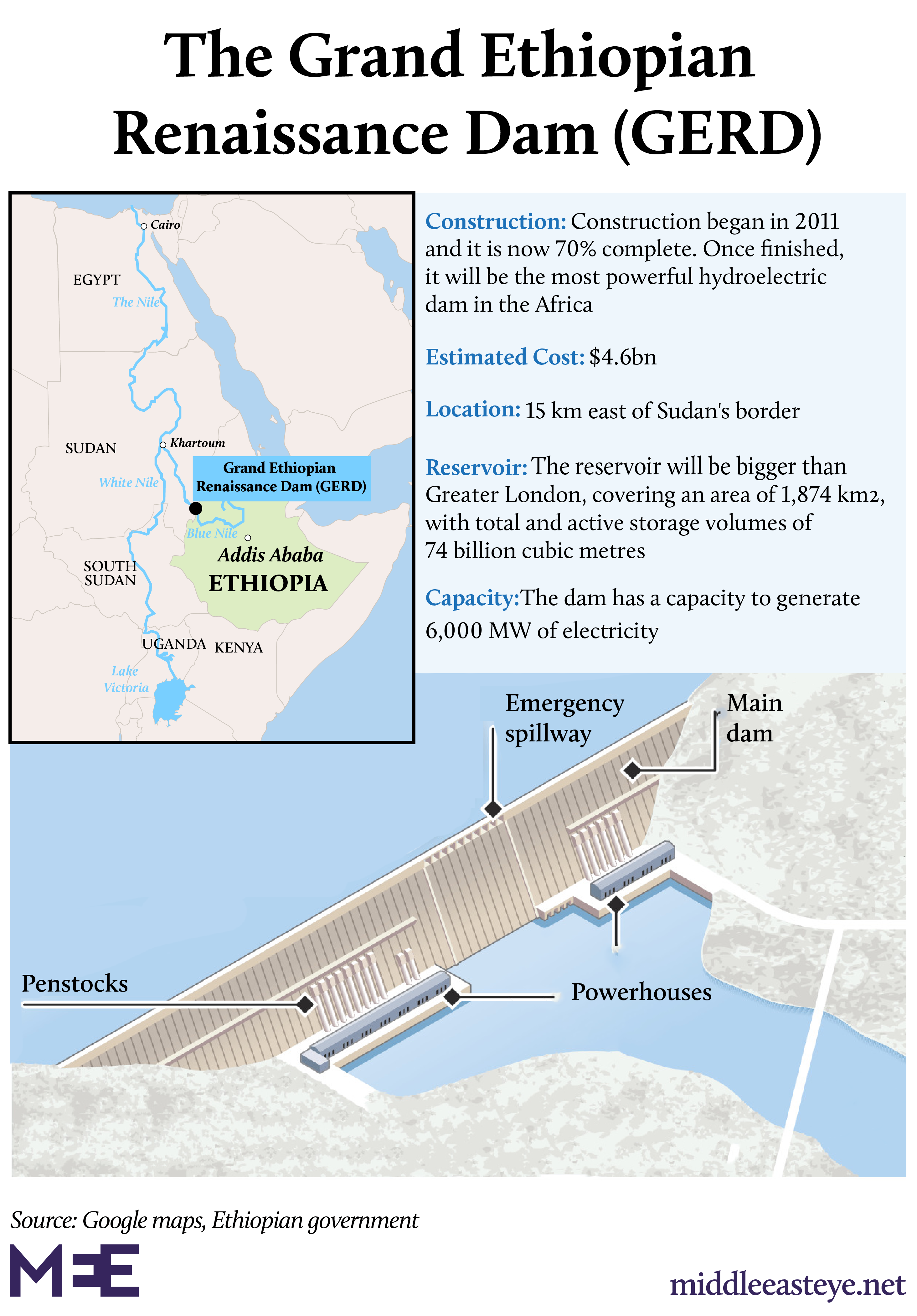

Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia have been negotiating for nearly a decade to reach an agreement on key outstanding issues related to the impact of the $4.6bn Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on their water security.

The three Nile Basin countries are continuing to engage in diplomatic talks, with Ethiopia repeatedly saying that it will start filling the dam reservoirs in mid-July, the start of its rainy season, whether or not an agreement has been reached.

Egypt and Sudan insist that binding agreements are needed to secure their future interests and water security, and must be agreed prior to the filling process.

Egypt relies on the Nile water for the vast majority of its water consumption and is concerned that the filling of the GERD will exacerbate a water shortage crisis in the event of a prolonged drought.

Construction of the dam began in 2011 and is more than 70 percent complete.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

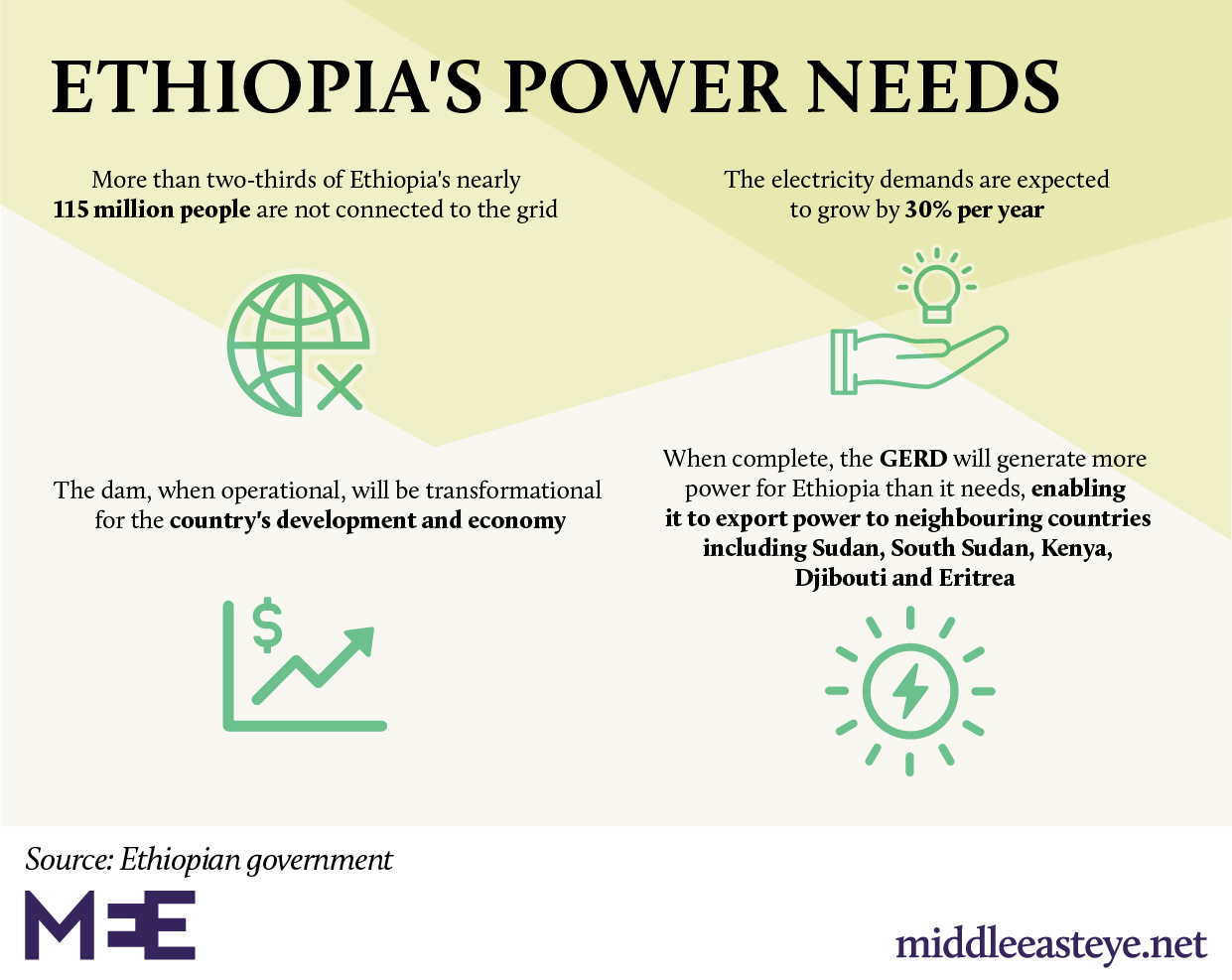

Ethiopia, the source of 85 percent of the Nile's water and the manager of the GERD, is primarily concerned about its own pressing energy needs and the potential of the dam to lift millions of its people out of poverty.

Once operational it will provide much-needed electricity for the country's nearly 115 million population, the majority of whom are not currently connected to the grid.

Sudan, Ethiopia's northern neighbour, has concerns regarding the potential impact of the construction of the dam on its own dams, and for the safety of its population and farmland from flooding that could result from faults in the construction or operation of the GERD.

The speed of the filling of the dam will potentially have an immediate effect on Egypt. If it takes five years to fill the dam, it will reduce Egypt's water supply by 36 percent and destroy half of Egypt’s farmland.

Although both Egypt and Sudan will suffer from water shortages caused by the construction of the dam, Egypt is projected to lose three times as much water as Sudan, according to one study.

Below is an outline of the main issues being discussed in the current talks and the history behind the dispute.

Issues dominating negotiations:

I: Drought mitigation

Egypt is mainly concerned about the management of drought during the years of filling and operating the dam, as well as in the years that follow a natural drought.

If flood levels are high during the first filling, Egypt will not encounter any major shortage of water, according to Mohamed Abdel Ati, Egypt's minister of water resources.

The problem will occur if there is a natural drought either during the filling or initial operation years of the dam, the minister said in a recent interview.

A drought can either be man-made or natural. A man-made drought in the case of the GERD will occur because any water entering the dam's reservoir will reduce the amount of water going downstream to Egypt and Sudan.

In the event of a natural drought, with a dearth of rainfall upstream, Ethiopia may be called on to release water to Egypt and Sudan from the GERD, thus depleting the dam's reservoir.

It will then need to refill it, causing additional shortages downstream.

Egypt's proposals in the current talks are as follows:

- The filling: In case of drought during the filling, Ethiopia will generate a maximum of 85 percent of its electricity needs, slow down the filling process and allow water to reach Egypt to make up for the natural drought.

- The operation: The Aswan Dam reservoirs will be diminished after the GERD filling. Therefore, if drought occurs at that time, the GERD reservoir should be used to provide Egypt with water to make up for the reduction in the Aswan Dam.

Ethiopia initially agreed on the above proposals in Washington in February, then retracted its decision.

Addis Ababa insists that committing a specified volume of water during periods of drought would ultimately drain the reservoir, thereby impeding its ability to generate the electricity it badly needs, according to Daniel C Stoll, associate dean for global affairs at St Norbert College in the US.

It also believes that Egypt is trying to perpetuate what it regards as Egypt's unfair claim to substantial amounts of the Nile's waters, Stoll told Middle East Eye.

Ethiopia argues that any drought should also be mitigated by water stored in Sudan's and Egypt's dams, not just by the GERD.

II: Binding agreement

Egypt and Sudan have demanded a written, binding agreement between the parties regarding Ethiopia's commitments to prevent harm to the downstream countries.

Ethiopia has so far only made verbal pledges and refused to sign a binding agreement.

Addis Ababa believes that the 2015 Declaration of Principles (DOP) is sufficient to demonstrate its respect for the no-harm principle. But Egypt and Sudan argue that they cannot rely on its goodwill.

III: Dispute resolution

Whereas Ethiopia would like to settle future disputes through negotiations, Egypt and Sudan have been in favour of binding international arbitration.

Ethiopia opposes arbitration due to the absence of a Nile Basin agreement that could be used by international arbitrators to settle water allocation disputes.

Moreover, according to Stoll, Ethiopia believes that it enjoys a privileged position, given that it is the source of the Blue Nile and it has the ability to control the dam and what the flow will look like downstream.

It fears that arbitration will be a limit on its power and influence, therefore it prefers direct negotiations, Stoll told Middle East Eye.

IV: Dam safety

Sudan and Egypt have concerns about the safety measures implemented during the construction of the dam and the potential consequences of any faults in the dam for their countries.

For example, Sudan, which lies only 20km from the dam, is concerned that releases of water from the GERD have the potential to flood its Roseires Dam, if not coordinated properly.

It is demanding that Ethiopia provide more assurances on the management of the GERD's reservoirs and its safety standards.

In the event of the collapse of the dam due to faults in its construction, all of Sudan would be at risk.

II: The History

1902: The Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty

Designed to determine the borders between Ethiopia and Sudan, the treaty was signed between the Emperor Menelik and the British agent in Ethiopia, John Lane Harrington.

Article III of the treaty "achieved a long-standing British aim to safeguard the unimpeded flow of the waters from the Blue Nile and Lake Tana".

Text from the article reads: "His majesty the emperor MENELEK II, King of Kings of Ethiopia, engages himself toward the government of his Britannic Majesty not to construct or allow to be constructed any work across the Blue Nile, Lake Tsana or the Sobat, which would arrest the flow of their waters into the Nile, except in agreement with his Britannic Majesty's Government and the Government of the Soudan."

1929: Anglo-Egyptian Nile Waters Agreement

The agreement was signed between Egypt and Great Britain, which at the time represented Uganda, Kenya, Tanganyika (now Tanzania) and Sudan.

It granted Egypt the right to veto projects higher up the Nile that would affect its water share.

1959: Nile river bilateral agreement between Egypt and Sudan

The agreement gave Egypt the right to 55.5 billion cubic metres of Nile water a year and Sudan 18.5 billion cubic metres per year. The agreement allocated all Nile waters to the two countries.

1970: Egypt builds Aswan Dam

In July 1970, Egypt completed the construction of the Aswan High Dam across the Nile in the south of the country.

1993: Framework for General Cooperation between Egypt and Ethiopia

Signed between the then Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak and Meles Zenawi, the president of the transitional government of Ethiopia in July 1993.

The two countries agreed to settle their Nile water disputes under the framework of international law and based on expert discussions.

They also agreed that neither country would engage in any activity deemed harmful to the other's interests.

1999: The Nile Basin Initiative (NBI)

The NBI is an intergovernmental partnership of 10 Nile Basin countries: Burundi, DR Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, The Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda. Eritrea participates as an observer.

On 22 February 1999, the institution was established as a forum for consultation and coordination among the 11 countries for mutually beneficial sustainable management and development of the shared Nile Basin water and related resources.

(1997-2010) The Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA)

Developed over more than a decade, the CFA has yet to be ratified by Egypt and Sudan due to their reservations over article 14b.

The article reads as follows: "not to significantly affect the water security of any other Nile Basin States".

All countries (Burundi, DR Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda) agreed to this text except Egypt and Sudan.

The two countries propose the following wording: "not to adversely affect the water security and current uses and rights of any other Nile Basin State".

The CFA intends to establish a framework to "promote integrated management, sustainable development, and harmonious utilisation of the water resources of the Basin, as well as their conservation and protection for the benefit of present and future generations".

It aims for the establishment of a permanent commission, the Nile River Basin Commission (NRBC), that would serve to promote and facilitate the implementation of the agreement.

After Egypt and Sudan failed to agree on the CFA in 2010, Ethiopia embarked on the dam project.

2011: Ethiopia begins building the GERD

In a surprise move in April 2011, Ethiopia announced the beginning of the GERD’s construction after signing a $4.8bn contract with the Italian firm Salini Costruttori.

Egypt's interim government, which followed the country's 2011 revolution, expressed concern.

2012: International Panel of Experts (IPE) formed

The International Panel of Experts (IPE) was founded on 15 May 2012, comprising experts from Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia as well as international specialists.

The panel issued a report a year later, recommending additional impact studies. The three countries formed a Tripartite National Committee in 2014 to conduct the impact studies, but they have yet to be completed.

2015: Declaration of Principles (DOP)

Signed by Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia in Khartoum in March 2015, the DOP outlined a set of principles that should guide the establishment of the GERD, including mutually beneficial coordination; sustainable energy supply; prevention of significant harm to the three countries; equitable and reasonable utilisation of water resources; agreement on the first filling of the dam in accordance with expert recommendations; and the peaceful settlement of disputes arising from the dam construction.

2018: Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia form joint research group

The three countries formed the National Independent Scientific Research Study Group in May 2018 to assess the project’s impact, filling and operation.

2019: US Treasury and the World Bank observe tripartite talks

The 2018 study group failed to reach an agreement, giving way to further talks by the three countries in November 2019, this time in the presence of the US Treasury and the World Bank.

2020: Negotiations

29 February 2020: Ethiopia refuses drought mitigation agreement.

10 April 2020: Ethiopia proposes agreement on the first two years of filling.

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed proposed an interim agreement to cover the first two years of filling the dam reservoir, but Cairo rejected it, accusing Addis Ababa of trying to delay a comprehensive deal while going ahead with the filling process.

9 June 2020: Parties resume negotiations.

19 June: Egypt asks UN Security Council to intervene.

Egypt formally requested the UN Security Council to intervene and call Ethiopia back into the talks. In response, Ethiopia sent a letter to the council accusing Egypt of trying to exert pressure on it through the international venue.

15 June: Technical teams fail to reach a deal.

The technical teams of Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia convened in mid-June to reach a deal, but they failed to reach agreement on the key issues of drought mitigation protocols and a dispute resolution mechanism.

26 June: Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan leaders agree on African Union-led talks.

27 June: Ethiopia says it will start the filling in mid-July.

Abiy Ahmed says the three countries agreed to reach an agreement within two weeks (by 12 July).

29 June: UN Security Council encourages talks between the three countries.

Under-secretary-general Rosemary DiCarlo briefed the UN Security Council on the latest GERD crisis and hailed a recent agreement between the three countries to join an African Union-led process of talks on outstanding issues.

2 July: Egypt minister says he's hopeful the next round of talks will lead to agreement.

5 July: Egypt's minister of water resources says parties expected to reach an agreement by 11 July.

7 July: A spokesman for Egypt's ministry of water resources says Ethiopia remains unwilling to reach a compromise on the outstanding issues, while Abiy Ahmed reiterated his country's intention to start filling dam's reservoir in the rainy season that begins in July.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.