Youth movement takes on Brotherhood and taboos in Jordan vote

Jordan’s parliamentary election has seen the country’s streets plastered with posters for 230 lists competing for seats in Tuesday’s vote.

One list in particular has raised eyebrows. The Maan List, whose name means "Together" in Arabic, is vying for votes in Amman’s third electoral district, where its secular programme is seen by some as breaking taboos, but has prompted death threats from others.

Maan envisions itself as a crucial actor in restricting the spread of the Muslim Brotherhood whose Jordanian political wing, the Islamic Action Front (IAF), is also fielding candidates for the first time since 2003.

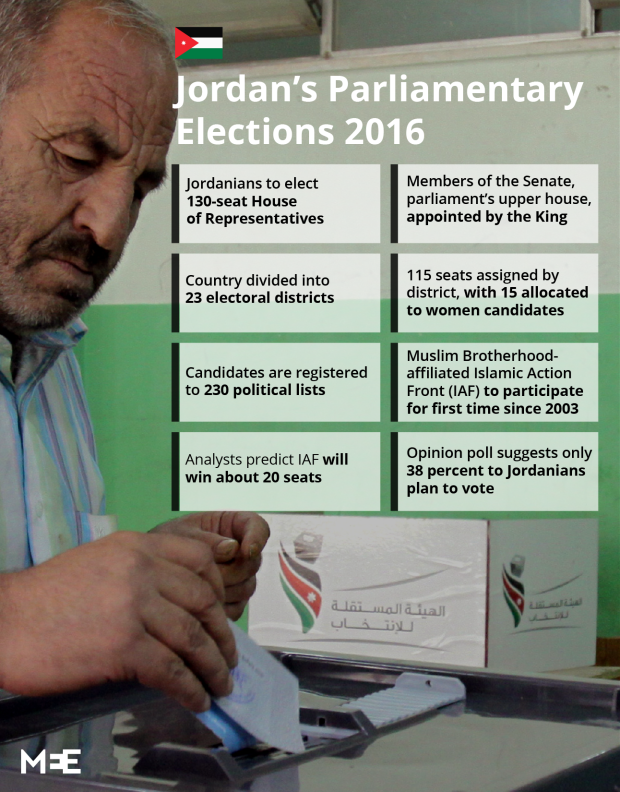

The IAF had boycotted the past two elections for the 130-seat parliament in protest over the previous electoral law, reformed this year, under which individual candidates rather than party lists were prevalent.

Under the new law, Jordanians vote for one list, specifying their chosen candidate within that list.

For many, this year’s elections signify a historic moment in the development of parliamentary democracy in Jordan, with some hopeful that the switch to lists will encourage the consolidation of parties with more focused political objectives.

“We are entering a new era,” said Mohammad Hussainy, political analyst and head of Jordan Reform Watch and Integrity Coalition for Election Observation.

In an interview with Middle East Eye, Kais Zayadin, who is considered Maan’s star candidate, outlined why the party had been turning heads.

Zayadin, who helped to found Maan in August, went viral on the internet recently for his protection of the arts in a debate against an IAF candidate who likened ballet dancers to prostitutes.

In response, Zayadin replied that the Muslim Brotherhood affiliate was “against civilisation”.

Maan has proved attractive to many young voters. The list’s well-designed posters display their programme in provocative slogans, proclaiming “no to the abuse of religion” and “against terrorism and extremism”.

Ismael Ghananim, a foreign language instructor, said he would have voted for Maan on Tuesday, if only he lived in the right electoral district.

“They are quite daring,” he said, by calling for a ‘civil state’ and equality between genders.

Death threats

Perhaps the list’s biggest gamble and most attractive proposition, the call for the separation of religion and politics, has garnered death threats, including threats of beheading, for Maan candidates.

“The concept of a civil state is still vague,” said Hussainy. “Some people understand it in a different way… as something against traditions and against religion.”

But Nada Atieh, who works in film production, said that Maan was breaking new ground in the Jordanian political landscape.

“For once we have a progressive, secular programme,” she explained. Both Atieh and Zayadin said Maan’s programme had “broken a taboo” in Jordan.

Several supporters of the list, who talked to MEE, said that it would be their first time voting, despite having been able to in previous elections.

Ghananim bemoaned traditional candidates who “perpetuate patronage and clientelism”. A common complaint, repeated by Zayadin, is that many enter politics just to further their business ties.

“I chose not to vote before,” said Atieh. “But this is what we want for Jordan.”

New youth party

Maan is not the only political movement amplifying the voices of Jordan’s young people. Shaghaf is a coalition of 5,000 young activists formed in June with the aim of oiling the squeaky gears of the country’s democratic processes.

MEE talked with Odai Harahsheh and Odai Bisharat, two of Shaghaf’s founders, about how the group seeks to transform politics from the grassroots up.

What makes Shaghaf particularly unique is that they have sought to decentralise the political landscape. Whereas Jordanian politics and business is typically centred in Amman, Shaghaf emerged “out of nowhere”, or more accurately, “outside of Amman”, said Harahsheh.

With voter turnout typically higher in governates beyond the capital, the coalition hopes to tap into a level of engagement that traditionally yielded little in the way of political returns.

Shaghaf launched itself with a meeting of 62 activists in central Amman, but by the end of that day, they’d had about 4,800 requests to join.

Ninety-five percent of their activists are aged between 20 and 30, and 40 percent are women, a staggering statistic given that all but one other political list have included only the mandated minimum of one female candidate.

Maan is the only other exception, with two female candidates.

Grassroots movement

Also striking is Shaghaf’s determination to remain an independent grassroots movement, with the coalition refusing offers of funding from external organisations.

Harahsheh and Bisharat stressed they did not want the movement to be swayed by the influence of any individual funder. Because of that, everyone in Shaghaf is a volunteer, and the group has spent just 100 dinars ($141) in their three months of organising.

“We’re trying to build trust between Shaghaf and the people,” said Harahsheh, the same kind of trust “people have lost [in] candidates and in decision making,” explained Bisharat.

By monitoring the proposed goals of candidates and how those are later realised (or not) in parliament, they hope to streamline the democratic process.

The thousands of activists, spread across the country working with Shaghaf, are split into working groups whose aim is to specify the local needs of citizens in each region.

The long-term aim is for Jordanian politics to become more decentralised and address the problem of a lack of investment and development in areas outside of the capital.

Another goal for the activists is to address the country’s chronic unemployment crisis, with joblessness currently almost at 30 percent, an issue that hits young people, who make up more than 70 percent of the Jordanian population, especially hard.

While reform movements in politics may bring to mind the Arab Spring, neither Shaghaf nor Maan see themselves in opposition to Jordan’s politically dominant monarchy.

“King Abdullah has a very good vision of a peaceful relationship with the people,” said Harahsheh.

Zayadin envisions Jordanian politics as a triangle: with the monarchy and government on top and the Muslim Brotherhood dominant in the left-hand corner.

He sees it as Maan’s purpose to act as a counterweight in the right-hand corner by speaking on behalf of the “silent majority”.

Moral agreements

By delivering the needs of local people to candidates in what they call a “moral agreement”, Shaghaf hopes that corruption will drop and “every single dinar will [be spent] in a good place.”

Most important, according to Harahsheh and Bisharat, is the need for direct investment in the regions, where they see opportunities for the tourism and agriculture sectors to thrive.

These agreements, designed by local Shaghaf activists, have been successful in their initial stages with 55 percent of candidates having signed.

However, Harahsheh stressed that the short span between the founding of the group in Ramadan and the elections was only a beginning. Next, local working groups will write policy papers to send to the government and monitor the successful candidates’ performance in parliament.

While both Maan and Shaghaf have high hopes for democratic development in Jordan, it’s unclear how successful either group can be.

Mohammad Hussainy said Jordan was not yet politically developed enough for Shaghaf to realise its aims.

“Lists are not ideal but are a good step forward,” he said, explaining that the electoral law needed to be further reformed to encourage the formation of political parties and blocs within parliament.

The proliferation of lists, loosely strung together and based on tribal origin or business ties, meant that many lists still lack a clear political programme, he added.

While Maan has gained praise for having a united programme, despite the different backgrounds of its candidates, most lists lack lack such a clear vision, and thus, said Hussainy, cannot be held accountable especially by groups such as Shaghaf which, he says, are ambitious but lack experience.

However, political analyst Sean Yom disagreed. While Shaghaf was inexperienced, he said, it had a “built-in platform for long-term operation” across the country, whereas Maan “exists purely for this electoral cycle”.

The primary danger for Shaghaf was co-optation by the state, in a similar fashion to youth movements which emerged in the wake of the Arab Spring during 2011-12. However, Yom said that was unlikely as Shaghaf was not seen a “direct threat".

Turnout crucial

For Maan, meanwhile, the greatest challenge may simply be persuading its potential supporters to turn up and vote.

A poll conducted by the University of Jordan’s Centre for Strategic Studies (CSS) predicted that 39 percent of Jordanians would not vote in Tuesday’s elections. Among those aged 18-34, the group that Maan most frequently appeals to, 46 percent said they would not vote.

Moreover, the most popular motivation for voting, at 24 percent, was a candidate offering a service to a voter.

The network of implicitly "buying" votes which Zayadin seeks to challenge may not be so easily broken, especially as influential businessmen, he said, were “using the poverty of people in order to gain their votes”.

In Amman’s third district, where Maan is running, voter turnout has never surpassed 20 percent and Zayadin acknowledged that increased voter turnout was crucial to success for the list - “if not, the Brotherhood will win”, for while Maan is a fresh face, it is estimated that the Muslim Brotherhood is supported by up to 30 percent of the population.

Yom believes that Maan, while bold, may struggle to assert itself even if it is successful in this election. “Maan might not even last long enough beyond the elections to merit attention,” he said.

“If the Brotherhood manages only 10-12 deputy victories, which is the general threshold that the government is willing to tolerate, then the entire point of having a secular civil state counterweight diminishes.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.