Instead of criminalising political speech, pass the NO HATE Act

On 29 December the Jerusalem Post published an interview with the US ambassador to Israel, David Friedman. In that article, Friedman stated that reactions were "largely emotional" to the Trump administration's announcement of support to move the US embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

He went on to state: "We expected the reaction, although we were disappointed with some of the rhetoric, which was ugly, needlessly provocative and anti-Semitic [sic]".

The charge of anti-Semitism has been increasingly used to silence or stifle legitimate criticism of Israel, its government, and its policies

The anti-Semitism charge

Friedman does not elaborate how political disagreements with an international policy change constitute bigotry against Judaism as a religion or Jews as a people. Nonetheless, the charge of anti-Semitism has been increasingly used to silence or stifle legitimate criticism of Israel, its government, and its policies.

Ken Marcus, Trump's nominee to the Department of Education's Office for Civil Rights, explicitly admits this in his own Jerusalem Post article, stating: "Israel-haters now publicly complain that these cases make it harder for them to recruit new adherents... Needless to say, getting caught up in a civil rights complaint is not a good way to build a resume or impress a future employer."

Perhaps the most important example of an overly broad definition of anti-Semitism is the Anti-Semitism Awareness Act of 2016, which passed the Senate but died in the House. The bill sought to enact a State Department definition of anti-Semitism meant for international monitoring agencies in Europe.

This definition, which mentions Israel 15 times, seeks to proscribe "blaming Israel for all inter-religious or political tensions" or using double standards for Israel, such as "focusing on Israel only for peace or human rights investigations".

Indeed, no other political entity is afforded such protection from criticism under US law, and surely such efforts violate the First Amendment's guarantee of free speech.

As Justice Thomas argued in McCutcheon v. FEC: "Political speech is the primary object of First Amendment protection and the lifeblood of a self-governing people [citations omitted]."

Criminalising criticism of Israel

Despite obvious constitutional infirmaries, efforts to enact this overly broad definition remain. The current Congress considered reviving the Anti-Semitism Awareness Act as recently as this past November in a House judiciary hearing.

Worryingly, earlier in December Bal Harbour, Florida passed an anti-free speech ordinance disguised as addressing anti-Semitism with the same broad definition, stating "the law directs officers to the State Department's 2010 definition of anti-Semitism..." in seeking to charge individuals with a hate crime.

These efforts to criminalise criticism of Israel not only limit political discourse on important topics such as foreign policy and US attitudes toward human rights abroad, they also trivialise the rising threat of anti-Semitic sentiment.

The latest FBI hate crimes report shows that anti-Semitic hate crimes increased by three percent in 2016 over the previous year.

If ambassador Friedman and Congress, back in session next week, are concerned with the state of anti-Semitism, they should oppose overly broad definitions of the term which merely seek to curb political expression and instead support comprehensive hate crime efforts such as the NO HATE Act.

Until then, the rhetoric of Friedman and others will only draw focus and resources away from legitimate hate crimes against the American Jewish community and their community centres or places of worship.

- Ryan J. Suto is government relations manager for the Arab American Institute (AAI). Prior to joining the AAI he worked with organisations such as UNDP Bahrain, the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy and FairVote.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

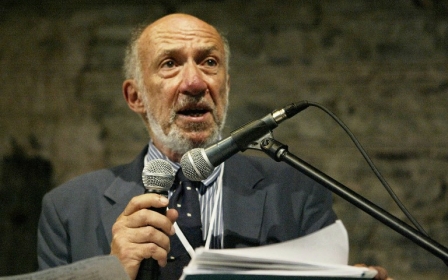

Photo: US ambassador to Israel David Friedman (AFP)

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.