A Socialist president for France? The stakes for Palestine

Foreign policy hasn't made headlines in the French presidential campaign. The French, naturally enough, are primarily concerned with issues directly impacting their everyday life, such as employment and health.

When it comes to international questions, therefore, it is likely that the French, who have been hit by several deadly terrorist attacks in recent years, are first and foremost interested the candidates’ policies on the “fight against terrorism”, both at home and abroad.

There is, however, one foreign policy issue that is of particular importance to many left-wing voters: the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. This issue has long aroused passions in a country with the largest Muslim and Jewish populations in Europe, often with direct repercussions in France. The idea of a “French intifada” has even been discussed.

While Socialist Party sympathisers - especially Muslim voters, the majority of whom vote on the left - tend to favour a solution respecting the rights of the Palestinian people, would the Socialist candidate Benoit Hamon live up to their expectations if elected as France's next president? Quite unexpectedly, the lessons of the past do not bode well. Here’s why.

Socialist France's role in the creation of Israel

French Socialist leaders from the outset have adopted policies favourable to Israel with regards to the question of Palestine. Even before the Balfour Declaration, it was a Socialist government that supported the establishment in Palestine of a Jewish state.

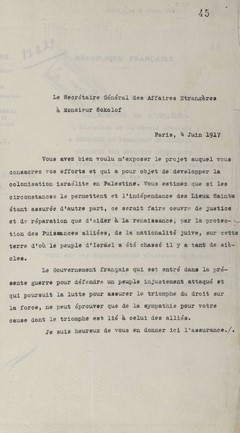

On 4 June 1917, in his letter to the president of the World Zionist Congress, Nahum Sokolov, the secretary general of French foreign affairs, Jules Cambon, wrote “it would be a deed of justice and reparation to assist... in the renaissance of the Jewish nationality in that land from which the people of Israel were exiled so many centuries ago".

At the time, French authorities did not merely intend to express their sympathy for Zionism. Their primary goal was to preserve France’s historical foothold in the region, in the name of protecting the holy sites of the Christian communities of Palestine.

For instance, Léon Blum, the Socialist prime minister of France’s transitional postwar government, was a staunch supporter of Zionism and the French endorsement of the United Nations 1947 Partition Plan for Palestine.

With the outbreak of the Zionist insurgency against the British officials in Mandatory Palestine, the Socialist government, then headed by Guy Mollet, seized the opportunity of weakening Great Britain, France’s historic rival, by supporting the Yishuv (the Jewish community of Palestine prior to the creation of the state of Israel) demographically and militarily by organising illegal immigration networks, providing arms and training Zionist fighters.

At the pinnacle of this relationship with the 1956 Suez Crisis, Mollet’s government formed a tactical alliance with Israel and Great Britain, now allied, to combat a common enemy – Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, reviled in France for supporting Algerian independence.

Mitterrand's illusion of balance

Though president Charles de Gaulle, who acceded to the French presidency in 1959, influenced a notable rapprochement between France and Palestine starting in 1967 in the aftermath of the Six-Day War – as would his successors Georges Pompidou and Valéry Giscard d’Estaing – the Socialists’ return to power in 1981 prompted a pro-Israeli turnabout in French diplomacy.

The election of François Mitterrand was warmly welcomed in Israel for that matter, where then-prime minister Menachem Begin hailed the arrival of a “friend, the great friend [of Israel], François Mitterrand".

The fact is Mitterrand’s sympathy toward Israel was clear from the start of his political career. A founder of the parliamentary council for the Alliance France-Israel, one of the most powerful pro-Israel lobbies in France, he was particularly critical of de Gaulle’s opposition to Israel during the Six-Day War.

His reaction to the vote of the UN General Assembly in November 1975, assimilating Zionism to racism, was symptomatic of his position: for him, the UN resolution was worthy only of “contempt".

Once in office, the Socialist president reversed the former government’s policies on the Palestinian question, advocating, for example, separate negotiations between Israel and Egypt whereas the Gaullists had insisted on the need for a global solution, and blocking the PLO legitimisation process that had begun under Giscard d’Estaing.

Though some would argue that this speech, and Mitterrand’s stance on the Israeli-Palestinian question in general, was a model of diplomatic balance – referring, in particular, to France’s rescue of the fedayeen and their leader in Beirut, in August 1982, and then in Tripoli, in December 1983, and to the fact that he would be the first French president, in 1989, to officially receive PLO leader Yasser Arafat – others maintained that the president’s actions were dictated not by a willingness to help the Palestinian cause, but by the political and economic interests of France in the Arab world.

As for his meeting in Paris with Arafat, Mitterrand had only agreed to it reluctantly (after turning down earlier applications from the Palestinian leader) and would seize the opportunity to pressure Arafat to amend the PLO national charter. In the end, the PLO leader was persuaded, memorably declaring on French television that same night that the charter was “obsolete”.

Hollande and Israel: 'La vie en rose'

Under the current Socialist president, the fracture between the party’s voter base and its ruling elite has never been so great. The Boniface affair is particularly revealing.

In 2001, Pascal Boniface, a university researcher who was then also the Socialist Party adviser for strategic affairs, sent a memo to François Hollande, then president of the Socialist Party. Hollande, Boniface wrote, needed to modify his position on the conflict in the Middle East so as to align it with the aspirations of the majority of their party sympathisers. "In a situation like this, a humanist, and especially a liberal, would see fit to condemn the occupying power,” he wrote. Pro-Israel circles launched an intense smear campaign against Boniface that eventually led Hollande and his collaborators to remove the researcher from office and to prevent him from representing the Socialist Party in any official capacity.

Ten years later, however, Hollande appeared to have taken his former adviser’s advice, making an official Socialist Party declaration – in the months preceding the presidential elections – urging Nicolas Sarkozy in the name of France to recognise the Palestinian state at the UN. The voters’ hopes would be quickly disappointed, however: Hollande did a turnaround once in office.

In August 2012, in his first foreign policy speech at the Annual Ambassadors' Conference, Hollande adopted a stance that many observers saw as being even more aligned with Israel than that of his predecessor. Not only did he fail to mention the establishment of a Palestinian state, but he also called for a resumption of negotiations “once the Palestinians had abandoned a good part of their preconditions” - as required by Israel.

Though Hollande did decide at the last minute, in late November 2012, to vote in favour of upgrading Palestine’s UN status to “non-member observer state”, he did so only reluctantly, forced by the deterioration of the situation on the ground, with the rise of tensions in Gaza, not following up the vote with a bilateral recognition of the state of Palestine, as more than 130 other countries had done in the wake of the vote.

Indeed, François Hollande, who in November 2010 signed an appeal published in Le Monde entitled “The Israel boycott is an unworthy weapon”, carried on with the policies of judicial repression against pro-Palestinian militants, initiated under Nicolas Sarkozy. These policies included the enactment of the Alliot-Marie circular - named after the minister of justice Michele Alliot-Marie - making France one of the few countries in the world to bring criminal charges against citizens who call for the boycott of goods from a country whose policies they criticise, considering it an “incitement to racial hate".

In fact, Hollande has avoided exerting any significant pressure on Israel whatsoever. For example, contrary to the UK or the Netherlands, France refuses to publish directives requiring retailers to use differentiated labelling for products from the settlements and, what is more, is suspected of having undermined the EU’s timid efforts to ban EU cooperation with Israeli institutions and companies operating in the occupied territories.

In short, despite the unsuccessful attempt to revive the peace process, or rather to “maintain the illusion of a peace process”, with the organisation of a peace conference in Paris last January, Hollande’s policies, including strengthened military cooperation between France and Israel and the adoption of the same hawkish position as Netanyahu on the question of Iran, have prompted some commentators to suggest that the ties between the two countries are as close today as they were at the time of the Suez Crisis.

As the French president told Netanyahu at an official dinner given at the Israeli prime minister’s residence in November 2013 - and the night before Hollande was to speak at the Knesset - he was ready to declare his “love for Israel and its leaders". The two countries, he said, could only see "la vie en rose".

Does Hamon dare?

The current Socialist Party candidate for president is said to be a longstanding supporter of the Palestinian cause. In 2010, at the time of the Israeli raid of a humanitarian flotilla bound for Gaza, in which nine activists would lose their lives, Benoit Hamon, then spokesman for the Socialist Party, accused Israel of having committed a “bloodbath”.

The man accused in certain right-wing circles of “Islamic-leftism” or of being the “candidate of the Muslim Brotherhood” has, in fact, attracted attention for his repeated calls for France to recognise Palestinian statehood. In October 2014, as parliament representative for the Yvelines (a department) and a member of the foreign affairs committee, he was among the initiators of a non-binding resolution drafted within the Socialist bloc of parliament calling on the French government to recognise Palestine.

He has reiterated this call as presidential candidate. During the last televised debate opposing Socialist Party contenders in late January, he said, “I don’t think a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is possible if the Israeli colonisation of territories continues. Palestine must be recognised.”

Earlier that month, in another televised interview, he even suggested that Israel could not be granted a special regime allowing the country to bypass international law and declared that he would be willing to recognise the Palestinian state and help make sure its transition to joining other states in the regional is peaceful. Hamon personally reiterated this commitment to the president of the Palestinian Authority, Mahmoud Abbas, when he visited Paris on 7 February, calling France’s official recognition “an indispensable prerequisite to the peace process".

In May 2016, the left-wing candidate sharply criticised his former prime minister and Socialist Primary rival, Manuel Valls, when the latter once more neglected to mention the recognition of the Palestinian state prior to a Paris-initiated peace conference. Hamon accused Valls of “beating a hasty retreat […] of surrendering at the request of the conservative Israeli government and dooming, in advance, the French initiative to being another shadow play pantomiming the peace process impasse".

However, critics accuse Benoit Hamon of being an opportunist motivated by electoral considerations. According to revelations in the November 2014 issue of the Canard Enchainé (a weekly newspaper), he affirmed that the parliamentary resolution on the recognition of the Palestinian state was “very timely as far as electoral support was concerned […] It is the best way to recover our voters in the suburbs and urban neighbourhoods who had misunderstood Hollande’s pro-Israeli stance, and who had given up on us at the time of the 2014 Gaza war".

That the Socialist candidate should take into account the expectations of his voter base is not a bad thing itself, but some would accuse him of doublespeak. According to his detractors, Hamon is privately opposed to the boycott of Israel, calling Israel a democracy – “though difficult to justify” – that is the victim of “stigmatisation”, maintaining, furthermore, that France has not done enough to effectively combat “anti-Semitism, and particularly that form of anti-Zionism that harbours anti-Semitism".

It is certainly somewhat disconcerting that in the 25 February open letter to François Hollande in which 153 MPs and senators urged the outgoing French president to officially recognise the state of Palestine before the end of his five-year term, Hamon was conspicuously absent.

This detail, particularly odd for a man who has repeatedly claimed the need for just such a recognition, and his presence at the dinner of the Representative Council of Jewish Institutions of France (CRIF), the most powerful pro-Israeli lobby group in France, has led some to jump to the conclusion that the Socialist Party candidate may not be all that impervious to pressures of Israel’s brokers in France. Not that his views are pleasing to these brokers anyway as the vice president of the CRIF, Gil Taieb, recently made clear with his call “to stop” Hamon in his race for president.

Therefore, though the mutinous candidate on the left of the Socialist Party has shown interest in the Palestinian cause and has made repeated declarations in favour of the recognition of the Palestinian state, these areas of doubt, together with his party’s noticeably pro-Israeli tradition, leave room for doubt regarding his determination to truly act in the interest of the Palestinians if he was elected. It’s up to him to prove the contrary.

- Elodie Farge has been an editor of the French edition of the Middle East Eye since its creation in January 2015. She has lived in the Middle East for several years, where she has worked for local NGOs defending human rights and where she was a researcher at PASSIA (Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs). She is the author of France & Jerusalem. “Holy” Conquests, Colonial Encounters & Contemporary Diplomacy (PASSIA, 2015).

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Socialist candidate for French presidential election Benoit Hamon talks with Palestinian National Authority President Mahmoud Abbas in Paris on 7 February 2017 (Twitter @benoithamon).

This article was originally published on Middle East Eye’s French page.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.