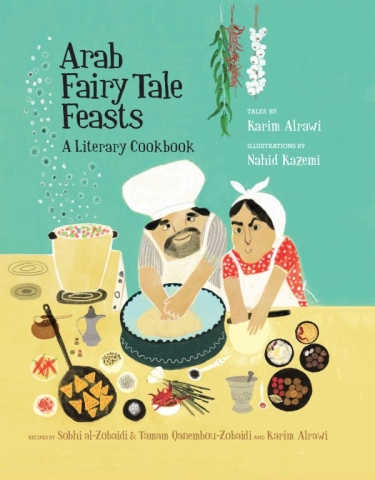

Arab Fairy Tale Feasts: Stories and recipes for the hungry young reader

“Nothing heals the body like a good meal, and nothing soothes the soul like a good story.” With this aphorism, Karim Alrawi opens Arab Fairy Tale Feasts: A Literary Cookbook, released this month by Interlink Books. This reading-and-feasting anthology, a combination of stories and recipes, makes a unique addition to the literary landscape for both children and their adults.

The first story-recipe combo in this collection sets the book’s tone. In Juicy Apricots, a sassy Moroccan girl named Malek climbs too high in an apricot tree while pilfering a neighbour’s fruit. When the gardener comes by and helps her down, she invents increasingly delightful excuses for why she was up in his tree.

This book is well-pitched at young readers, with short, tightly plotted stories and related fun facts; the sort of book a child can read and re-read.

In the recipe for mehallabeyat qamaruddin, or “apricot pudding”, that follows, Alrawi provides both a short explanation of the dried fruit-paste sheets (qamaruddin) used to make the dessert, and which are particularly popular around Ramadan, as well as a recipe simple enough for pre-teen children.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

If a publishing house can have a sweet tooth, then this fairy tale literary cookbook may just be Interlink Books’. The US-based publishing house, founded 25 years ago by Palestinian writer and editor Michel Moushabeck, has made its mark with translated literary fiction, collected folktales, and lushly-illustrated cookbooks, including recent recipe collections from the Baltic states, Syria, Afghanistan, and Portugal.

All these interests converge in a unique new genre: collections of culturally specific and easy-to-make fairy tale feasts.

Arab Fairy Tale Feasts is the third book in their “fairy tale feasts” series. Like the others, it’s aimed at readers and eaters aged 8-12.

The fairy tales and facts are by Egyptian author Karim Alrawi, who writes in his introduction that he is following in the tradition of great Arabic cookbooks “by offering a combination of recipes, illustrations, and stories to give the flavour of Arab culture".

Instead of food photos, there are delightfully whimsical illustrations by Iranian artist Nahid Kazemi. and the kid-friendly recipes were a collaboration between the author and Palestinian-Canadian restaurateurs Sobhi and Tamam al-Zobaidi.

The series also includes Jewish Fairy Tale Feasts (2020), by Jane Yolen and her daughter, Heidi Stemple, with illustrations by Sima Elizabeth Shefrin, and Chinese Fairy Tale Feasts (2014), by Paul Yee, with illustrations by Shaoli Wang.

The recipes are a mix: there is North African couscous and harissa, Levantine hummus and manakish, Gazan fish soup, and Egyptian koshary

In Arab Fairy Tale Feasts, Alrawi doesn’t collect traditional tales. Instead, his own original, modernised folktales play off familiar themes. Readers will find the wise fool Goha - inspired by the seventh-century Abu al-Ghusn Dajin al-Fazari in Kufa, and thirteenth-century Seljuk satirist Nassreddin Hodja - as well as a transgressive Abu Nuwas, and the djinn and ghouls from A Thousand and One Nights.

The stories are set all across the Middle East, with the first opening in Marrakesh and the last ending in an unnamed Gulf country, on the coast of the Arabian Sea.

The recipes are also a mix: there is North African couscous and harissa, Levantine hummus and manakish, Gazan fish soup, and Egyptian koshary. And, of course, there couldn’t be a cookbook for children without desserts. Recipes for maamoul, kunafa, and qatayef are all adapted for younger and less-patient chefs.

Each story is followed by an aphorism, such as the one that follows The Juicy Apricot: “The wit of the mischievous should be a warning to the wise.”

There are then one or two accompanying recipes, and recipe facts for the curious, giving miniature histories of the humble-seeming chickpea, the lentil, and the grain of couscous.

For children who have eaten these dishes but never had a hand in making them, the recipes are an excellent chance to break them down into bite-sized steps. For children who may not be familiar with staples such as zaatar or harissa, it’s a chance to try out new flavours and textures.

Among the book’s two dozen recipes, there are simple ones that take hardly any effort at all, such as the pomegranate spritz, alongside the more time-consuming multi-step recipes, like the arayes kufta, translated in the book as “lamb puffballs”.

Most of the recipes probably require an adult assistant, at least for younger chefs. But plenty of them are sufficiently quick that young cooks won’t lose interest. For the less adventurous eater, spice is suggested as an option, but not required.

The recipes are not as simple as in some cookbooks for children. But they teach important kitchen skills, and the results are a lot tastier than in basic, and often bland, cookbooks for kids.

As Alrawi hints at in his introduction, Arab Fairy Tale Feasts isn’t just stories and recipes. What really makes it special is how he situates his book in the long history of Arabic food writing. His brief and accessible introduction gives readers a quick overview of the history of Arabic cookbooks, starting in the tenth century with Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq’s Kitab al-Ṭabikh (Book of Dishes).

Alrawi’s introduction also highlights the way in which food - like fairy tales - changes as it travels. He details, for instance, how a sweet-and-sour meat dish moved from Persia into Arab countries as al-sikbaj, and then to Spain, where it was called escabeche, and to Latin America, where it became ceviche.

Throughout the collection, fact boxes appear, in which young readers will find the connections between words and stories, foods and histories.

After A Juicy Apricot, for instance, readers are told that the English word “apricot” comes from the Arabic al-barqouq, and that the Arabs imported apricots from Iran and China, where they were first grown.

We also get a quick discussion of how apricot seeds can be ground and mixed with coriander to make dokka (a mixture of spices and nuts often eaten with olive oil, as a snack), or turned into an oil to soothe dry skin.

Clever widows and princesses

The stories all have a traditional fairy tale flavour, with animal tales, tricksters, and quests. But Alrawi manages to fold in several strong and clever women characters.

While a traditional tale might present a king with three sons, each sent out on a seemingly impossible quest, Alrawi’s The Dream Garden has a king with two older sons and a young daughter, and it is Princess Soraya who uses her wits both to save the royal family and to bring back jewels from the king’s dream garden.

And while some of the stories are set in unnamed, faraway kingdoms, others have more contemporary settings. Fish Soup in Gaza, for instance, is set on the waterfront of the besieged Palestinian enclave of Gaza, between the wharf and al-Shati refugee camp, called “Beach Camp” in the story.

In the tale, a young girl named Fadia outwits the wise Goha character, who claims he has caught a fish as large as an ocean liner. She one-ups him by saying she knows of a ceramics centre in Khan Yunis where they can fire a pot “three times the size of al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem.”

When he says that’s ridiculous, she tells him they must have pots that large. Otherwise, how would he have cooked that fish he caught?

The delightful illustration at the end of the tale, in which a young girl winks at the reader, makes the story even cheekier and more delightful.

Another short fable, The Story and the Chickpea, foregrounds a girl named Salwa in Sanaa, Yemen. A story wants to escape from Salwa, while Salwa struggles to hold it in.

This story wants to be heard so badly that it sneaks out of Salwa and up-ends the soaking chickpeas. In the end, Salwa tells her mother her story and is finally able to rest.

In the recipe that follows, children needn’t sort and soak their chickpeas overnight but are offered the easier option of using tinned ones instead.

The stories are fun and irreverent, with the tricksters, widows, and young children generally winning out over the stiff, the stodgy, and the greedy. In The Last Supper, a group of gossipy middle-aged men schemes about how they might outwit a wealthy widow named Bashira.

They decide to tell her it’s the end of the world and, since the world is ending, she should throw them a fancy party. The crafty Bashira does indeed throw them a party. But while they stuff their faces, she sells off their fancy cloaks and turbans and donates the money to charity. After all, she tells them, if the world is ending, surely they would want to secure their spots in heaven!

There are a few unfortunate holdovers from the stereotypes of fairy tale language, such as the “wise old African openbill stork” that appears in the story of Why the Chicken and Ostrich Cannot Fly.

But, for the most part, the stories are updated to feel both timeless and contemporary. They take their young readers on a quick tour of different cities and landscapes, full of bright children, silly adults, and feasts fit for a hungry young reader.

As well as being an excellent gift and keepsake, the book is also a very handy kitchen resource. In the end, it’s hard to know whether this collection should be kept in the kitchen or on a child’s bedroom bookshelf.

Arab Fairy Tale Feasts is available from Interlink Books

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.