Troy's plunder: Where the East and West first clashed

The British Museum opened Britain’s first major exhibition on Troy in 140 years this week, a stunning show of 300 objects and artworks, and a fresh 21st century take on Homer’s story of the Trojan wars.

Troy: Myth and Reality, open until March, brings alive an epic tale three millennia old, with its violent heroes, and brutally mistreated women, of a mythical clash of East and West that has enthralled every generation and general since.

The stories of mythical Troy are laid layer on layer, just like the excavated ruins of Hisarlik, in Turkey

The show is anchored by the treasures that Heinrich Schliemann, a self-promoting German businessman adventurer turned archaeologist, spirited out of Turkey in the late 19th century, to the fury of Ottoman rulers of the time, and finally deposited in Berlin’s museums.

It includes the first showing in London since 1870 of Schliemann’s finds, though it’s the artistic renderings of Homer’s eternal tale, from 500 BCE to 2019, that first draw the visitor in.

The women of the Trojan war

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

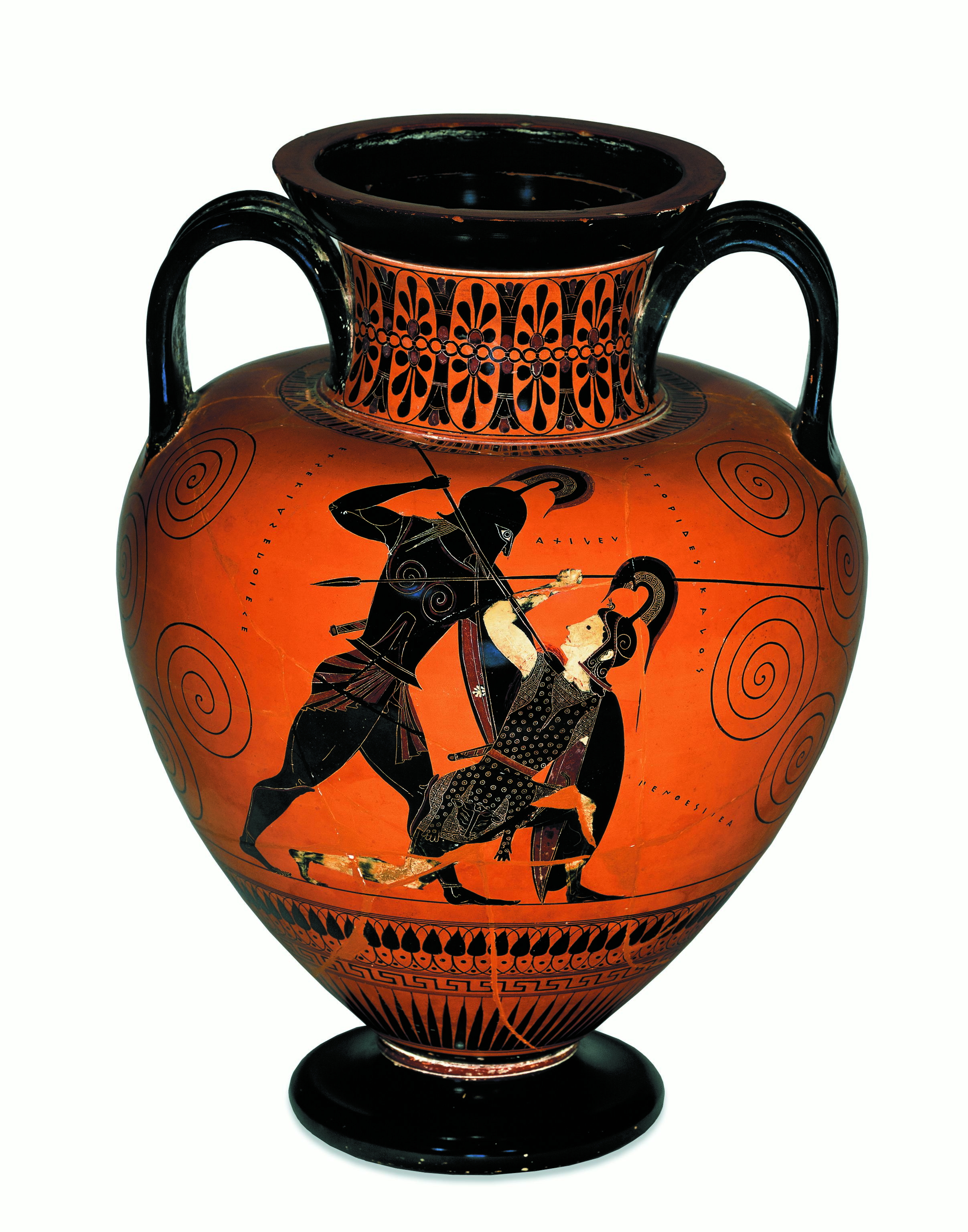

Exhibits range from magnificent 5th century BCE Greek vases showing the raging Greek hero Achilles slaughtering Amazon woman warriors and virtually everything else in his path, to extraordinarily accomplished Roman paintings, via coins and carvings, and critically Trojan pottery, to Brad Pitt’s ill-fated turn in the 2004 film Troy, trashed on its release as a “cartoonish joke”.

There is moving footage of Syrian women refugees performing a version of Euripides’ classical tragedy The Trojan Women, in a production that was a sell-out success in Britain in 2016 and when it was performed again this year (though the Syrian artist Reem Alsayyah, who made the show Queens of Syria, has condemned the exhibition’s backing by the BP oil company).

Three out of four curators who worked on the exhibition and its remarkably insightful catalogue are women. After lavishly exploring how vengeful, mostly naked male warriors, particularly Achilles with his vulnerable heel, hacked and hewed each other across the Trojan plain, before destroying the city in a grisly bloodbath, the exhibition’s closing section is devoted to the women of the Trojan war.

Helen, a pawn in a divine quarrel; Cassandra, and her discarded warnings, proved entirely true. Queen Clytemnestra, who “acts fearlessly” in murdering her returning husband the Mycenaean King Agamemnon in his bath, after he sacrifices their daughter Iphigenia to improve the shipping forecast.

The truth about Troy

Archaeologists and ancient historians still question whether Troy, a great Anatolian city, was destroyed by the Greeks, or even if Homer was a single person. But Turkey’s Professor Rüstem Aslan, the archaeologist who has studied the site for 30 years and headed Turkey’s Troy excavation since 2013, has no doubt.

“Of course,” Rüstem told Middle East Eye, when asked if the Trojan wars actually took place, probably in the late Bronze age around 1250 BCE, on the coast of north-west Turkey. “I cannot say everything which you can read in the [Homer’s] Iliad and Odyssey is a historical event, but I believe there was a war between Trojan allies, and a Trojan army, and the Mycenaeans, not only one Trojan war but several huge conflicts.”

Tantalising references from the Hittite empire in Anatolia to a major conflict, archaeological remains including evidence of destruction at the right period, and Homer’s own writing, all add up, he said. “I believe there was a Trojan war.”

Whatever the truth of what happened at Troy, the show makes wonderfully clear why Homer’s Illiad has fascinated political and military leaders from Alexander the Great in the 4th Century BCE, to Mehmet the Conqueror in the 15th Century, to Turkey’s founder Mustafa Kemal Attaturk in the 1920s.

From the elopement, or abduction, of Paris and Helen, the face that launched a thousand ships, to a wooden horse that still warns of Greeks bearing gifts, the story of Troy and its passionate characters of both Gods and humans has been told and retold in every century.

The British Museum director Hartwig Fischer notes in the exhibition’s catalogue how when Sultan Mehmed II captured Constantinople for the Ottoman Turks in 1453, he was said to have finally exacted revenge for the ancient Greek sack of Troy. “Sympathies clearly lay with the Trojans in that period,” he writes.

The stories of mythical Troy are laid layer on layer, just like the excavated ruins of Hisarlik, in Turkey, show some nine Troys piled one on the other through history. But the evidence is there of an early encounter between East and West, the exhibition curators say, from trading ties to military rivalry, at the very least a struggle for regional power in the Aegean between Mycenae in Greece and Troy in western Anatolia.

“Troy the ill-omened, joint grave of Europe and Asia,” are the words of the Roman poet, Catullus, on the wall of the exhibition’s first room. “Troy, of men and all manliness most bitter ash.”

The treasures of Troy

Schliemann, armed with others’ research, decided that Hisarlik was Troy and staged his excavation there, ploughing through several layers of remains to find, most famously, a silver and gold hoard he called “Priam’s Treasures”, with the fabled “Jewels of Helen” including a gold headdress.

He smuggled them out of Turkey by steamship, dressed his young wife in the jewels, and offered them to the British Museum for an extortionate price, before giving them to Berlin’s museums.

At the end of World War Two, the Russians seized the most precious items, which first reappeared in the Pushkin Museum in 1993. The British Museum is showing important pottery and other Schliemann finds loaned from Germany but the glittering gold treasures on display are German imitations; the originals have not left Russia.

The furious Ottomans jailed Schliemann’s Anatolia assistant following the discovery. But British Museum’s keeper of Greece and Rome, J Lesley Fitton, says he curried favour in later excavations, paying compensation so that Turkish authorities even gave him another permit to dig at Troy.

“Clearly as far as they were concerned the matter was closed, and he paid his dues and his debt.”

Schliemann got many of his facts wrong, declaring a set of ruins to be Homer’s Troy that were a thousand years off.

He worked in California’s gold fields, but after his treasures were examined in Russia, claims he faked them were disproved, says Fitton.

“There was huge suspicion, but I don’t believe a word of it myself,” she said. “The accusations in his lifetime as well as subsequently have been quite sharp and bitter. People have particularly focused on Priam’s treasure, that he either accumulated it from different spots of the site, or he had goldsmiths in the back streets of Istanbul making it.

“When experts were able to see the treasure with their own eyes [in Russia] it appeared that it was incredibly coherent as a group,” Fitton said. “Incredibly close in every respect to exactly what you’d expect of jewellery and vessels around 1250 BC.

"This is my take on it. He was clearly a difficult man, but not ‘a psychopathic liar’,” she said.

Of Schliemann, Turkey’s Professor Aslan, who did not work on the British Museum’s Troy exhibition, shrewdly observes: “There is not only one Schliemann, everyone has their own Schliemann, like everyone has their own Troy.” While he destroyed and smuggled, he established Hisarlik as Troy.

'Lost heritage'

The London exhibition comes less than a year after Turkey opened a major new Troy museum, a $10m modernist cube near Hisarlik in Anatolia, where Schliemann first excavated in 1871 on a site where some nine layers of differently dated Trojan ruins are layered on top of each other. That museum includes a section on “lost heritage”, objects that Turkey officially wants back.

'The Homeric epic is very important for Turkish culture and Turkish people'

- Professor Rüstem Aslan

The Troy museum’s displays include a long-term loan of “Troy gold” jewellery from the University of Pennsylvania, which bought them in 1966.

“According to me, of course, all the finds should come back to Troy,” Aslan said, though whether it’s possible is a political issue. “I don’t know if I can see it, but it’s the dream that all the finds and treasure should be exhibited one day under the roof of the Troy museum.”

Next year, he will pursue another dream. With about 50 people working on current Troy excavations, he hopes new evidence may reveal the location of Troy’s burial grounds. “Former excavation directors before me, they tried to find the Bronze age cemetery, but all of them couldn’t find it,” he said.

The Trojan Wars came to stand for the first time the Greeks had successfully united to face a common enemy from the East, the British Museum catalogue notes. Alexander the Great supposedly slept with Homer under his pillow, it is claimed, as he led his campaigns into Persia and the East. In turn, the Greek-speaking Mehmet II had three copies of the Illiad in his famous library, Aslan noted.

The exhibition relates how British officers arriving at Gallipoli in World War One, armed with their classical education, wrote poetry evoking Achilles in the trenches.

Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, after defeating the British in the Dardanelles and the Greeks in Anatolia, like Mehmet, is said to have spoken of revenge.

Both Turks and Europeans were fascinated by the idea they descended from the Trojans, after the mythical Trojan survivor Aeneas supposedly founded Rome, following the path of a modern refugee.

Even the last 20 years have proved how “the Homeric epic is very important for Turkish culture and Turkish people,” said Aslan, as well as “the cultural collective memory of humankind”.

Turkey has been investing heavily in this cultural heritage - the site of Troy was declared a national park in 1996, a pioneering master plan was drawn up to protect it, and planning for the museum began in 2010. Publishers in Egypt and elsewhere are planning Arabic translations of his books, Aslan noted.

The last major European show on Troy, in Stuttgart in 2001, saw close to a million visitors and produced a surge in German travellers to Anatolia, according to Aslan. The site drew an estimated 700,000 visitors last year, with the new Troy Museum about 120,000 for 2019, perhaps 20 percent of them Turkish.

With new visitor facilities, multilingual guides and disabled access, numbers will surge, Aslan said - particularly with a likely blockbuster London show. If nothing else, a new touristic invasion may soon set sail for western Anatolia’s shores.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.