Iran elections: Everything you need to know about June presidential vote

On Friday 18 June, Iranians will be heading to the polls to elect a successor to outgoing President Hassan Rouhani, a moderate reformist who has been in office since 2013.

This election comes with high stakes. Negotiations are ongoing with the international community on Tehran’s nuclear programme and sanctions that have crippled its economy.

The next few years will also be crucial to the future of the highest political and religious office in the country, with current Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei now 82 years-old. Whether hardliner or reformist, the president - who remains subordinate to the supreme leader - could shape the direction in which the Islamic republic is headed.

With this explainer, Middle East Eye seeks to clarify the process through which presidential candidates are chosen prior to the popular vote, introduce those running in 2021, and look back at the often ill-fated former heads of government in the 42 years of the Islamic Republic.

The Guardian Council: Gatekeeper of elections

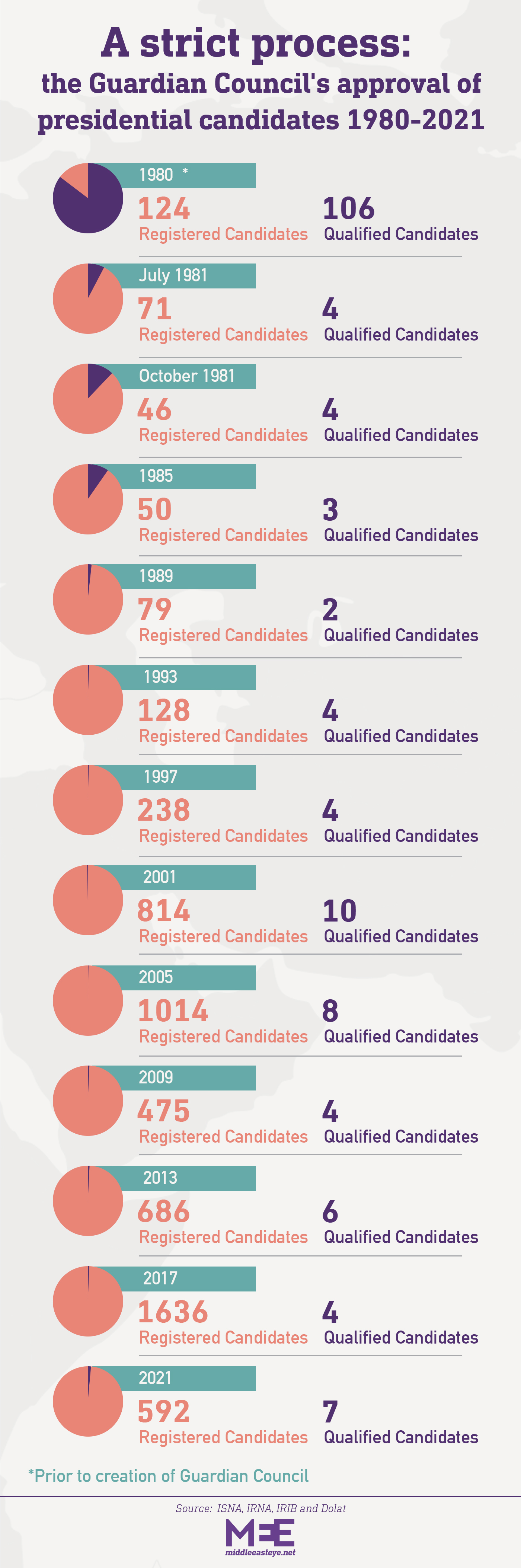

Since the Islamic revolution in 1979, Iran has held 12 presidential elections. Aside from the first election, which took place in January 1980, all other votes have taken place with the Guardian Council vetting candidates before they can officially run for office in two rounds of popular voting.

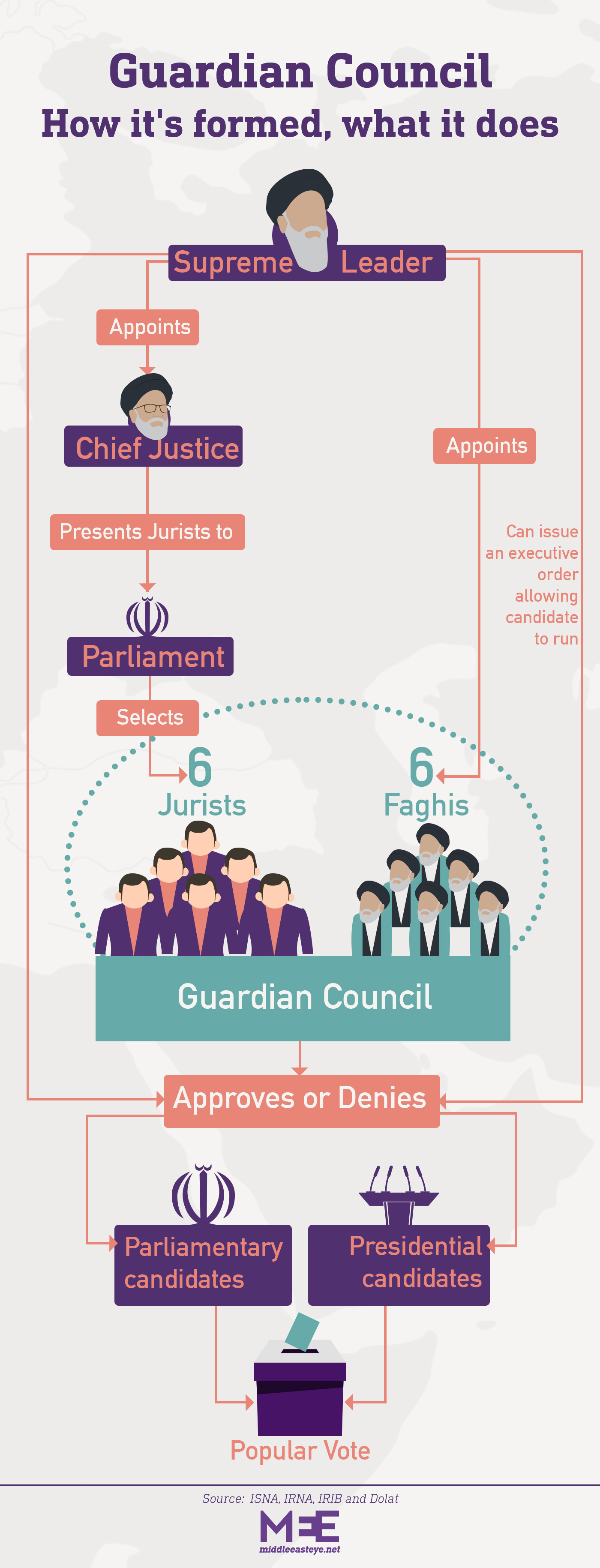

To fully understand the role played by the Guardian Council, one must first see how it is formed. The government body is composed of 12 members, all serving six-year terms: six Islamic clerics - also known as faghis - and six jurists. The faghis are directly appointed by the supreme leader, while Iran’s chief justice presents a pool of jurists to Parliament, which goes on to select six of them for the council.

But who appoints the chief justice? The supreme leader. And who vets candidates running for Parliament? The Guardian Council.

Even the approval of candidates is not the exclusive purview of the Guardian Council - with the supreme leader playing a big role behind the scenes.

Many well-known political figures ask the supreme leader for permission before throwing their hat in the ring. This year, Khameini notably advised Hassan Khomeini, a grandson of Iran's first supreme leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, not to enter the race.

Meanwhile, the supreme leader can also intervene with an executive order - known as hokme hokumati - to allow a candidate disqualified by the Guardian Council to run.

However, like the composition of the Guardian Council itself, the process of approving or barring candidates is opaque. From one election to the next, the very same person might find themselves disqualified - like former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, elected in 2005 and 2009, and blacklisted this year.

The first presidential election in 1980, before the creation of the Guardian Council, saw 106 out of 124 candidates allowed to run by the interior ministry - an 85 percent approval rate.

Since the council was instituted, however, the rate of candidates allowed to run for presidential office has drastically dwindled. On average, just over 1 percent of people who registered as would-be candidates since 1981 have been approved to be on the ballots.

Most of those whose names would never appear on Iranian ballots were ordinary citizens. However, many prominent political figures who served in the Islamic Republic’s establishment for decades have been among those disqualified by the Guardian Council, often depending on the ebbs and flows of their relationship with the supreme leader.

Among them was Ebrahim Yazdi, once Khomeini’s closest advisor who helped devise the political plan that led to the establishment of the Islamic Republic. After falling out with the first supreme leader, Yazdi was disqualified from running for president in 1985, 1997 and 2005, before dying in 2017.

Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, the son of a wealthy pistachio merchant from central Iran, served as Iran’s fourth president from 1989 to 1997. Known as one of the founding fathers of the Islamic Republic, the hardliner helped pave the way for Khamenei to become the country’s second supreme leader in 1989 - only to be barred from running for president again in 2013, after he fell out of favour with Khamenei.

This year, the dismissal of Ali Larijani’s candidacy by the Guardian Council came as a big surprise. A military officer for the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) for ten years, parliament speaker for 12 years, and currently serving as an adviser to Khamenei, the moderate conservative has always shown loyalty to the supreme leader. His absence in the 2021 election has been interpreted by some analysts as a deliberate move to shape the race in favour of conservatives.

The 2021 pool of candidates

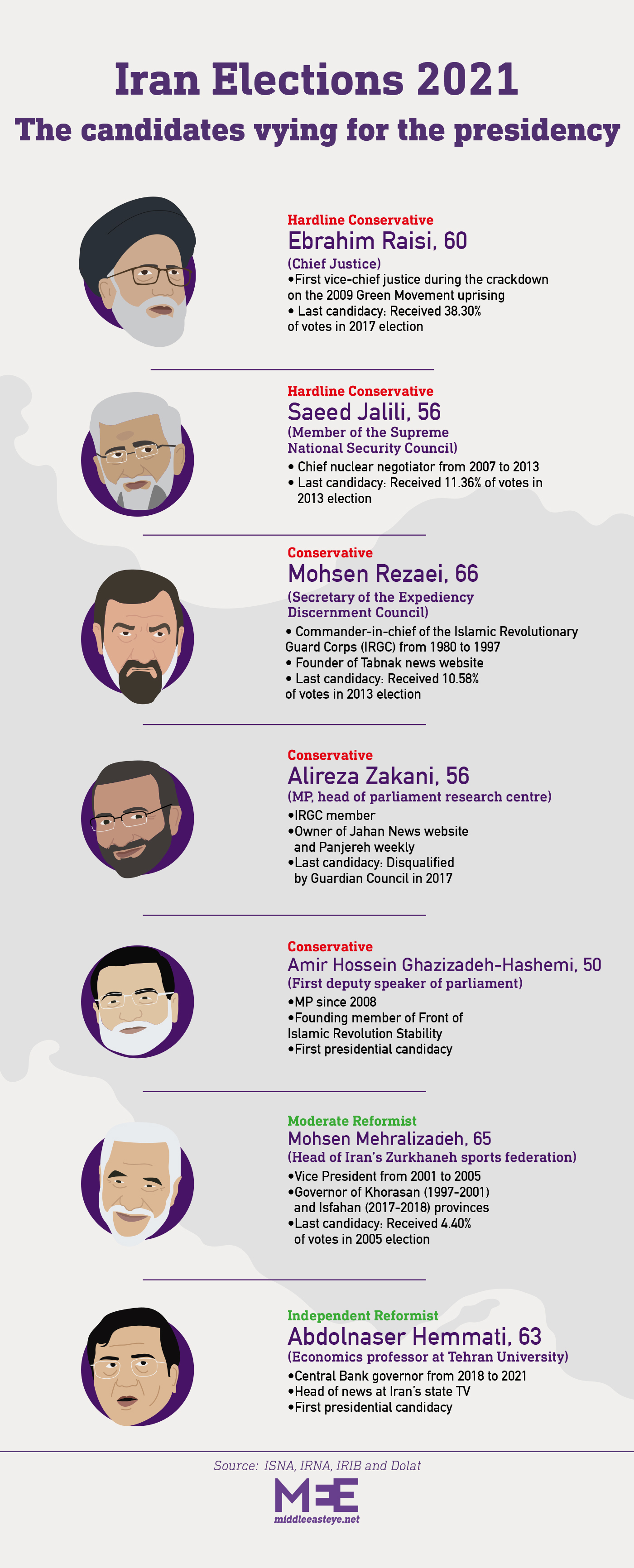

This year, seven out of 592 candidates have made the cut and are officially competing for the presidency - five conservatives and two reformists.

When the Guardian Council disqualified many reformist and moderate candidates in the February 2020 parliamentary election, leading to an overwhelming victory for conservatives at the time, analysts had forecast that the council would follow a similar path ahead of the presidential election.

However, no one had expected that prominent conservative figures like Larijani would be barred from running - leading many to speculate that the lack of heavyweight candidates was specifically designed to pave the way for the candidate preferred by the IRGC and Khamenei, Chief Justice Ebrahim Raisi.

When the final candidates were announced, Raisi said that he had opened negotiations to let other candidates enter the race “to make the election more competitive”. Complaints about the Guardian Council’s list of approved candidates were short-lived, however, as Khamenei has not challenged the council’s move to only qualify seven candidates as of a week before the vote.

So who are the seven men currently vying for the presidency?

First off is Raisi, the hardliner expected to win. The chief justice has a history of involvement in the suppression of dissent in Iran. He was one of four clerics in the so-called “death commission”, which ordered the mass execution of more than 4,500 leftist political prisoners in 1988. Over two decades later, Raisi would be the first vice-chief justice during the crackdown on the Green Movement - the mass protest movement contesting the results of the 2009 presidential race that saw Ahmadinejad re-elected.

The other conservatives include Saeed Jalili, another hardliner and member of the Supreme National Security Council, a position to which he was appointed by the supreme leader. A member of the IRGC and the Expediency Discernment Council, an advisory body to the supreme leader, Jalili was also the chief nuclear negotiator from 2007 to 2013.

Mohsen Rezaei, a more moderate conservative, is currently the secretary of the Expediency Discernment Council - also by the supreme leader’s appointment. He served as commander-in-chief of the IRGC from 1980 to 1997, and founded conservative news website Tabnak in 2007.

MP Alireza Zakani, another conservative candidate, is also a former member of the IRGC, and owns two news publications - Jahan News and Panjereh. He was also the head of the student branch of Iran’s notorious Basij paramilitary group during the 1999 student uprising, during which members of the militia torched university dormitories and beat students.

The final conservative in the running, Amir Hossein Ghazizadeh-Hashemi, currently serving as first deputy speaker of parliament, was also one of the founding members of the Front of Islamic Revolution Stability (Jebhe Paydari), the main political faction that supported Ahmadinejad during his time in office.

The first of two reformist candidates, Mohsen Mehralizadeh, is currently a board member of the Kish Free Zone Organisation - one of the first free trade zones established by Rafsanjani - and the head of Iran’s Zurkhaneh sports federation. Serving as vice president under Mohammad Khatami from 2001 to 2005, his presidential candidacy was initially rejected by the Guardian Council in 2005, but he was allowed to enter the race after Khamenei weighed in, scoring 4.40 percent of votes.

The final candidate, Abdolnaser Hemmati, has been touted by some as the dark horse who could be the reformists’ best shot at the presidency this year. An economics professor at Tehran University, he also served as governor of the central bank from 2018 until May, when his presidential candidacy was approved. Like other competitors in this race, he too has a history of involvement with the media, serving as head of news for Iran’s state television IRIB from 1981 to 1991.

President of Iran, a risky job

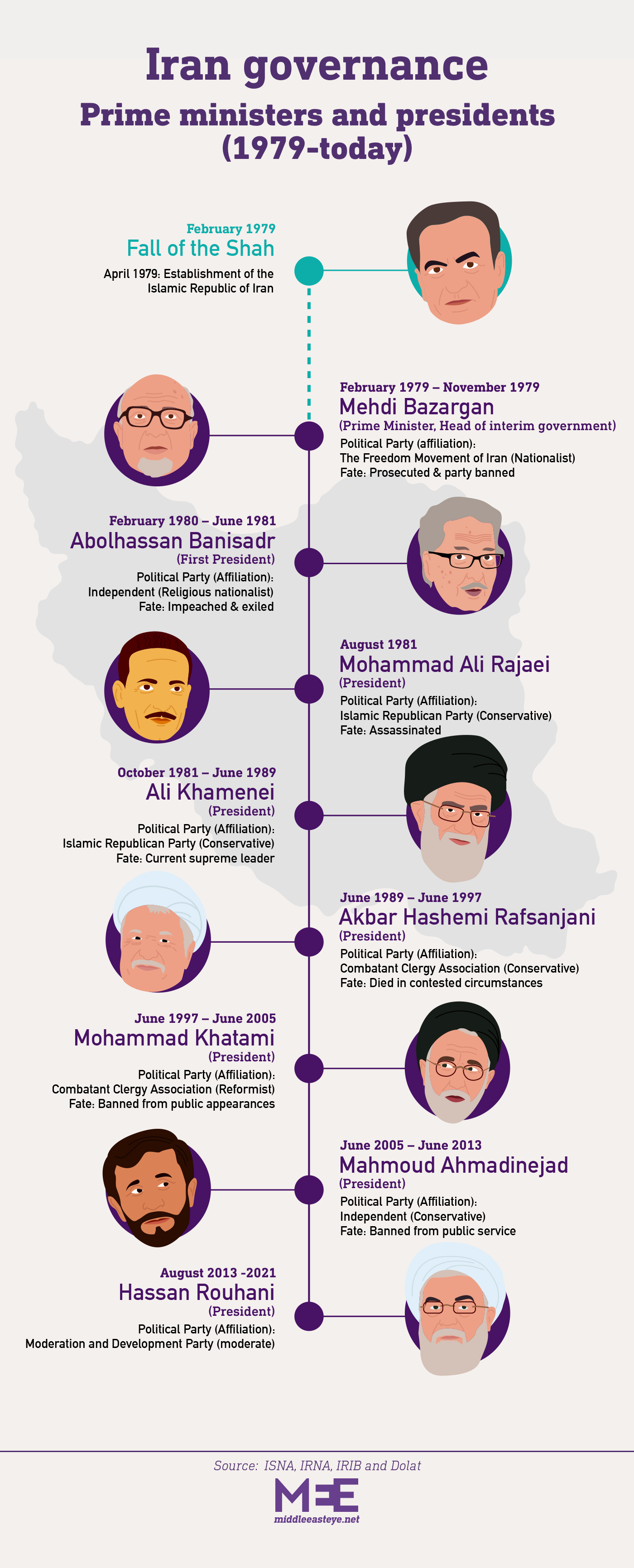

Whoever is elected this month will become the eighth president of the Islamic Republic - and ninth head of government, if one counts the first prime minister before the presidency was established.

But in the decades since the 1979 revolution, none - bar one - have met particularly auspicious fates in the wake of their presidency. Aside from Khamenei, who became supreme leader in 1989 right on the heels of his two terms as president, all the others have ended up either dead, exiled, prosecuted, under house arrest, or ousted from the sphere of power.

One common thread seems to bind all these ill-fated men together: having run afoul, at one point or another, of the supreme leader.

Mehdi Bazargan, Iran's first prime minister, resigned after nine months in office due to his opposition to Khomeini's velayat-e faghih ideology establishing the basis for the political rule of the clergy in Iran. Following his resignation, Bazargan's political influence rapidly declined as he and his party, the Freedom Movement of Iran, came under fire from hardliners. Bazargan was prosecuted, his party would eventually be banned, and the former prime minister died in exile in Switzerland in 1995.

Abolhassan Banisadr, Iran's first president, was also an opponent of velayat-e faghih. After a little over a year in power, parliament - with Khomeini’s full support - impeached Banisadr due to his opposition to the clerics’ grip on power, and he was forced to escape the country. To this day, he lives in exile in the French city of Versailles under police protection.

The third president, Rafsanjani, was the leading lobbyist and a kingmaker who paved the path for Khamenei to become the country’s second supreme leader after Khomeini’s death. However, he later became a victim of Khamenei’s monopolisation of power in the country, as he slowly saw his influence wane and was barred from running in the 2013 presidential elections. In 2017, Iran’s state-run broadcaster announced that Rafsanjani had died of a heart attack in a swimming pool. His daughter, however, has claimed that her father was killed by people close to Khamenei.

Mohammed Khatami was expected to be obedient to the supreme leader when he was elected president in 1997. However, he became the symbol of reform in Iran, pushing for fewer social restrictions in the country and ushering in an era of increased press freedoms. But Khatami's attempts to change the system fell through. By the time he stepped down in 2005, he had been banned from public ceremonies, and Iranian media are to this day prohibited from publishing any images or news regarding his activities.

Ahmadinejad, perhaps one of the most notorious Iranian presidents in recent decades, was an unknown figure when elected president. However, he had the support of the supreme leader and the IRGC, who were keen to replace Khatami. His re-election in 2009 was heavily disputed at the time, leading to the popular Green Movement protests, which were aggressively repressed.

Four years later, Ahmadinejad too fell out of favour with the supreme leader and found himself pushed out of politics, while many of his aides and allies were arrested and imprisoned. He was barred both in 2017 and 2021 from running once again for president.

Meanwhile, Rouhani has never publicly opposed Khamenei during his two terms in office. But with many rivals in the IRGC and among conservatives, the fate of his political career remains uncertain once his term comes to an end.

Now, the very position of president is seemingly at risk, with some hardline MPs pushing for the role to be removed and for the premiership, abolished in 1989, to be restored - a move that would consolidate power in the hands of the largely conservative religious leadership in the Islamic republic at the expense of direct popular elections.

The tightly controlled political process has left many Iranians increasingly disenchanted - with only 37.7 percent of respondents to a recent poll saying they would vote on 18 June. After some four decades under the same political system, the average citizen is by now well aware that the decisions that weigh the most occur long before they head to the polling station.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].