'The last days of agriculture': Squeezed Tunisian farmers eye EU imports with concern

Sitting in the restaurant of his farm in the lush Beja agricultural region, Zied Ben Yousef praises Tunisia’s farming potential, which he says goes all the way back to the days of the Roman Empire.

Ben Yousef’s farm specialises in the production of cheese, which he sells in a local shop and delivers to the capital. He also teaches students about cheese production methods and agriculture.

His goal is for people to come to the region, located two hours from Tunis, and enjoy his homemade products.

But the competition from Europe and other domestic producers is fierce.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

It’s impossible, he says, to export to the European Union because of health standards and the Tunisian market is increasingly dominated by big multinationals, leaving small farmers under pressure.

“We are in the last days of agriculture in Tunisia,” he says.

Ben Yousef is not alone: many Tunisian farmers are squeezed these days between a sector with little government investment, slowly being taken over by large producers and landowners, and a marketplace that benefits subsidised imports from elsewhere.

Their woes are just one thread of wider concerns over Tunisia’s volatile economic situation.

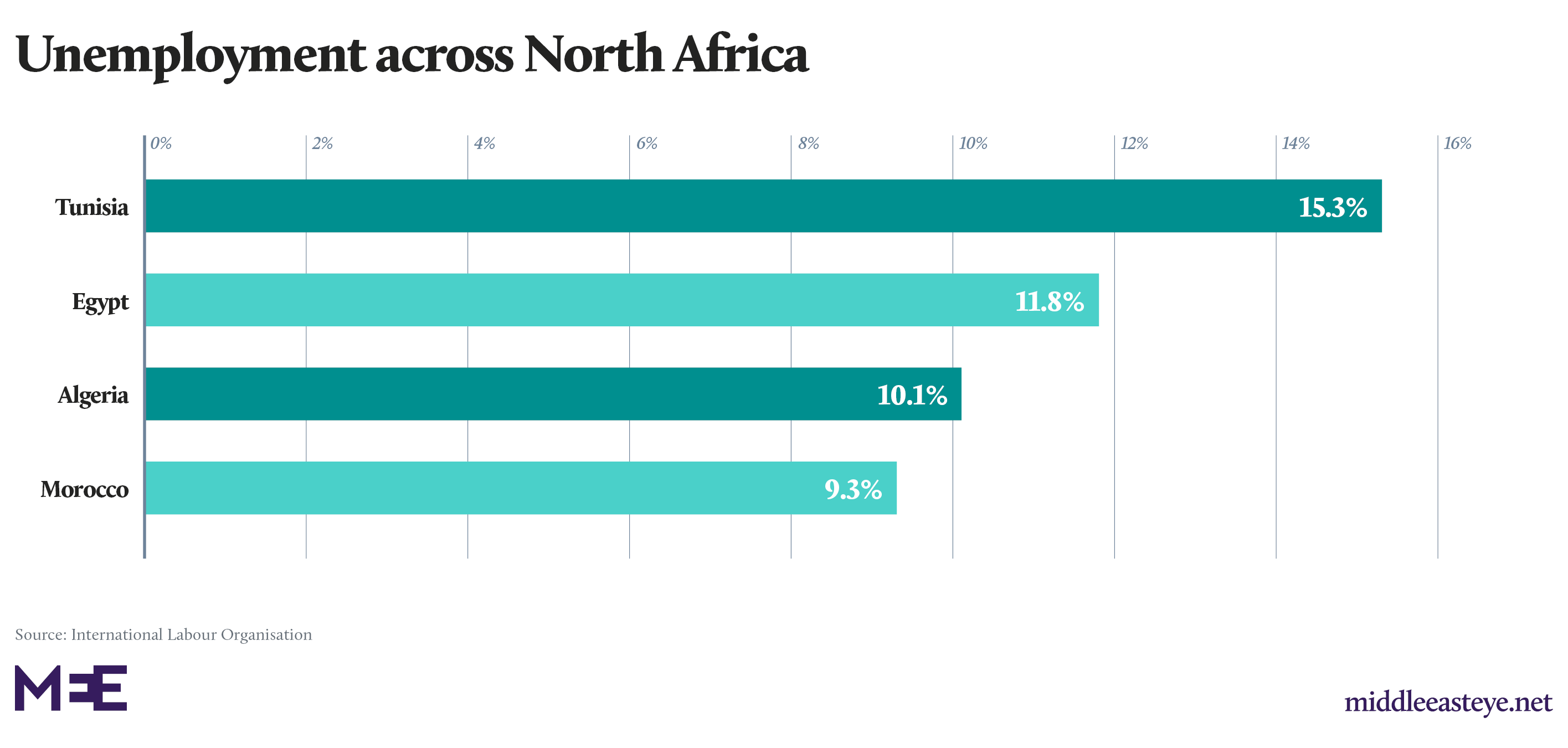

Hailed as the success story of the Arab uprisings, the country has since found it difficult to grow its gross domestic product, while unemployment has remained high, particularly among university graduates.

The government is struggling to drive economic growth, while cutting budget and trade deficits under pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The IMF has pushed the government for years to freeze public sector wages - a large part of government expenditure - sparking mass protests and strikes.

In February, following months of widespread demonstrations, the government agreed to raise public wages after a long dispute with the country’s largest trade union. Yet it is not clear how the government will actually foot the bill.

Amid all this, ongoing negotiations with the EU to establish a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area – mostly known in Tunisia by its French acronym ALECA - have caused a stir and sparked renewed fears over Tunisia’s economic future, particularly among farmers and their advocates.

'We are in the last days of agriculture in Tunisia'

- Zied Ben Yousef, Tunisian farmer and cheese producer

According to the EU perspective, the deal will “ensure a better integration of Tunisia's economy into the EU single market”.

“The EU is supporting economic development in Tunisia,” says Beatriz Knaster Sanchez, head of the commercial section of the EU mission in Tunis, telling MEE that it was in the EU’s interest to have a stable neighbour in the south.

But farmers and advocates like Habib Ayeb, head of OSAE, a civil society organisation, say the negotiations strike them thus far as “neo-colonial policies,” and that the deal seems to represent a European attempt to build its markets without concern for Tunisians.

“With ALECA we will be forced to have our doors wide open to producers that are more powerful than us. Our products can’t be competitive in this kind of market,” Ayeb told MEE.

New markets for European producers

In 1995, Tunisia and the EU signed an agreement which created a free trade area for certain products between the union and Tunisia. ALECA would extend the agreement to the service and agricultural sectors and, depending on the final terms, selected farm products could freely flow between both countries.

That is if the deal is ever agreed. So far, the two sides have met three times since 2015, without an agreement.

One reason for the delay is widespread criticism of the negotiations among Tunisian civil society groups.

A major fear is that, as a result of EU subsidies and mass production, Europe can produce cheaper products than Tunisian farmers and that it will be these products which enter and dominate the Tunisian market.

What does Tunisia grow - and what does it import?

+ Show - HideFarmers in Tunisia grow a variety of products. The country is a major player in the global olive oil market, being the world’s third-largest exporter.

Tunisia is also a major exporter of dates, which are mostly grown in the south. Other major farm products include tomatoes, citrus fruits and almonds.

Overall however, the country is a net importer of agricultural products such as wheat, soybeans, corn and raw sugar.

In 2017, Tunisia imported agricultural products worth several hundred million euros from the EU.

“One aspect of securing their agriculture is to find new markets for European producers,” said OSAE's Ayeb, explaining that the EU strategy is to become an even bigger agricultural player. “ALECA is part of this game,” said Ayeb.

There are concerns, in particular, about how ALECA could affect small farmers already struggling to compete in the domestic market. Around 80 percent of those working in agriculture are small farmers and breeders, said Karim Daoud, president of the Tunisian farmers’ union (SYNAGRI).

“Particularly for small farmers, many of them women, it will be difficult to catch up with European standards and regulations while at the same time facing competition for land and water by agrobusinesses propped up by foreign investors,” says Thomas Claes, project director at the Friedrich Ebert Foundation in Tunis.

In this regard, says Daoud, it is “extremely important” that financial and human resources are brought to Tunisia as the country currently cannot fulfil European requirements, including those which would help local producers meet EU sanitary standards for exports.

Upgrades to move closer to European health standards are estimated to cost hundreds of millions of dinars and implementing structural changes, he says, would probably take no less than 15 years.

Beyond the issue of market competition, critics say the free trade negotiations threaten Tunisia’s ability to produce food to feed its population domestically. Much of Tunisia’s economy is export-oriented.

'They have all this and don’t produce to feed people'

- Habib Ayeb, OSAE

Over time, says Ayeb, big investors are becoming the main producers, currently managing around 30 percent of agricultural land.

With a lot of their production geared for the international market, consumers at home risk losing access to foods produced in their own country, critics say.

"Big investors have all of the advantages. They own the land, have access to credit and are part of an international trade network," Ayeb says. “They have all this and don’t produce to feed people.”

Unfounded fears?

While some Tunisians fear the worst, Knaster Sanchez, an EU trade official, says other North African countries that struck agricultural trade agreements with the EU “are greatly benefiting from such agreements, and fears that they would be invaded by EU agricultural products did not materialise”.

As part of the negotiations, she said, Tunisian products could be temporarily sheltered from competition through transition periods, while others with more market potential could be included.

And not all Tunisian farmers are opposed to a greater opening of the Tunisian market.

Naher Ben Ismail, who leads a high-end olive oil business in the Beja region, told MEE his company was already exporting olive oil to Japan, France and Canada.

“We don’t have a problem with European trade,” says Ben Ismael, adding that his business was generally interested in outside investment.

He did, however, acknowledge that Tunisia’s economic problems have had a negative impact, as the recent currency devaluation made it more expensive, for example, to import the Italian olive oil bottles that he uses.

For companies already exporting to the EU, Claes of the Friedrich-Ebert Foundation told MEE, “ALECA might improve their position,” adding that most of their products were already covered by the existing agreement.

In contrast, those in already marginalised areas of Tunisia’s interior “will not benefit from export opportunities, foreign direct investment or new jobs in the service sector”.

Need for political agreement

Tunisia’s volatile economic and political situation are closely intertwined as a general strike in January showed. Key sectors in the country were ground to a halt as the country's largest trade union held a one-day strike in protest at the government's failure to raise public sector workers' salaries.

So, as negotiations with the EU continue, says Daoud of the farmers’ union, ALECA must “first and foremost be a political agreement” that takes into account Tunisia’s “political, economic and social situation” and guarantees the success of the country’s democratic transition.

Sanchez of the EU mission saw it as a positive sign from a democracy perspective that civil society had been so actively involved in the ALECA consultations.

But Daoud worries that discussions have so far been too heavily driven by commercial considerations.

The eventual agreement, in his view, could be a tool to improve relations between Africa and Europe. The key will be how the negotiations unfold.

“ALECA can be a real danger if we negotiate in haste without having a global view on this agreement,” he said.

Negotiations could begin again as early as this spring.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.