Fire and the Phoenix asks us to rethink the roles of religion, clan and power

Reading Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddimah (Prolegomena) can induce contrasting feelings about what it means to be an Arab. On the one hand, this monumental work can leave us with a feeling of pride in belonging to a refined Arab culture; on the other hand, it leaves us in no doubt that Arab civilisation has reached what Ibn Khaldun would call "a standstill in the history of nations".

The study of the past triggered - and still triggers - enormous intellectual efforts to find a way out of this overwhelming standstill, one which hampers the progress of Arab societies. While historians try to provide us with accurate facts and historical records relating to what happened, and thinkers and philosophers revisit the past to discover the root causes of decline and to prescribe a renewal of civilisation, fiction writers retell what has happened in an attempt to chart the emotional fabric that illuminates the nature of the blockage in the history of Arab culture and civilisation.

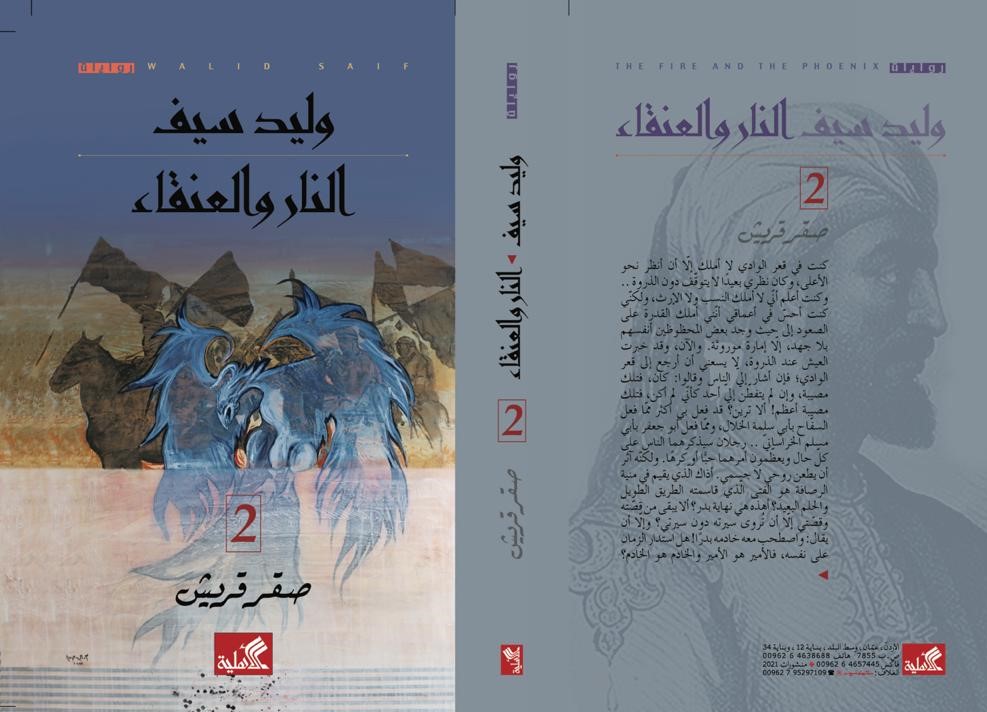

Through his literary masterpiece Fire and the Phoenix (A-Nar wa L-Anqaa), Waleed Saif uses his outstanding talent to convert a historical narrative into a repository of human emotions, thus allowing us to probe deeper into the origins of the Arab cultural impasse. The exploration of the inner lives of the main characters, through the use of an impressively incisive and scrutinising language, sheds light on how human agency shapes and is shaped by power.

Through his literary masterpiece Fire and the Phoenix, Waleed Saif uses his outstanding talent to convert a historical narrative into a repository of human emotions

Through the character of a woman voicing her concerns about her transformed husband, Saif writes: "My husband, really my husband? I mean… sometimes I feel as if I were with a distant stranger, and I am inclined to think if only I had married the meek, poor saddler he used to be! Is it the sultanate that does all this to men, father? Or is it only men with oppressive power, men capable of violent tyranny who can attain to the sultanate?"

On a similar note, the main character, Abd al-Rahman, the founder of the Umayyad dynasty in Andalusia, puts his feelings about power into words, saying: "This is the state of the sultan; we fabricate it and it ends up fabricating us, then obliges us to difference heart from sword."

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

The captivating narration of such moments of contemplation about the relationship between the sultan as a man of power and as a lover, or as a violent ruler and an ordinary citizen, thrusts the reader into the heart of a fundamental conundrum. Saif’s dissection of the emotions of the main protagonists reveals that at the core of the emotional fabric of power lurks an ineradicable feeling that, when it comes to reigning, there are only two options: either you reign or you covet the position of the reigning power.

All the underhandedness, the intrigues, the conspiracies, the killings and the murders are perpetrated either to preserve or to gain power.

Blurring the lines

The historical events narrated in Fire and the Phoenix and in other works by Saif are an attempt at untangling the emotions underpinning a medieval culture, where blurring the lines between ruler and ruled is inconceivable; where ruling is for life. The philosophical rumination and intellectual exchange between the protagonists conjure up images of a political culture where it is incongruous to associate "transmission of power" with the idea of the ruler remaining alive. It is the rule of the game of power that the new enthroned sultan sits on the corpse of a deceased one.

Saif uses a highly evocative style to help the historical details form a backdrop against which the dialogue of the protagonists crystalises into political maxims of immutable rules of power and aphorisms that act as leitmotifs.

One of these maxims says, "the sultan from castle to grave", emphasising the dire straits in which the ruler finds himself, having no choice but to cling to power to stay alive. The sultan, according to this maxim, cannot afford the luxury of a peaceful retreat from power - for power kills power, which results in never-ending bloodshed.

"Kingdom is sterile" is another maxim meant to convey the sultan’s emotional conflict between the survival instinct that dictates the elimination of close family members in order to preserve power and the binding affection that ties the sultan to these members. The sultan, Abd al-Rahman, unifier of Andalusia, resuscitator of the Umayyad dynasty, saviour of his clan from the persecution of the Abbasid rulers in the east, orders, without the slightest hesitation, the decapitation of one of his beloved nephews.

Saif describes how the sultan resists a feeling of guilt while his soul is tormented. "Before incurring both the blessings and troubles of the sultan," says Saif, "Abd al-Rahman used to interpret the Arab saying ‘kingdom is sterile’ as an indictment, but now he takes it as a vindication.

Yes, kingdom cannot be but sterile, if the goal is to preserve the state from rivalry between members of the same family inclined to conceive of it as a booty seized during one of the tribe’s raids, or a fruit farm or a fenced land they vie to inherit. The Umayyad state in Andalusia? Yes! A state, in the first place, ruled by one man of the Umayyads, who will bequeath it to his son after him, a son capable of its protection. He who disobeys is the enemy, whether he is a commoner or a member of the clan."

Killing 'the snake in its egg'

Al-Marouani, one of Abd al-Rahman's advisers and a member of his clan, ascribes the falling of the Umayyad dynasty in the east to leniency towards their enemies. Had they nipped in the bud their enemy’s ideology, or "killed the snake in its egg", as Marouani puts it, the Umayyads would have preserved their dynasty.

The reason they were wiped out is that they did not heed the basic rule of power, the rule which says that "the inescapable destiny of the sultan is that he had no third choice; either ‘you or your enemy’. Otherwise, it is better you renounce the throne. In case you cling to your title, be the first to attack your enemy, unless he attacks you. Don’t give your enemy the benefit of the doubt".

The historical events narrated in Fire and the Phoenix are an attempt at untangling the emotions underpinning a medieval culture, where blurring the lines between ruler and ruled is inconceivable

Saif’s Fire and the Phoenix depicts how Abd al-Rahman, the survivor of an atrocious tribal cleansing, came to appreciate servants and commoners with whom he rubbed shoulders during his escape from his persecutors, and then how he ended up insulating himself from them when he became a sultan. In one of the most incomprehensible moves, Abd al-Rahman dismissed his loyal and faithful servant, Badr, who played a decisive role in establishing his reign and organising his army.

The poor Badr, who cherished the illusion that historians would mention his name alongside his master’s, spends the rest of his life in solitude away from the castle in the middle of nowhere, with no benchmark in the universe but his beloved wife’s grave in front of his pondering eyes.

At a previous stage of their dangerous journey to Andalusia, Badr told Abd al-Rahman: "This is real life, master! Not the one you were used to in castles. Yet, is this despicable person in front of us greedier than the noble people who were ingratiating themselves with you, even when they were wealthy enough to feed, from their money and lands, thousands of poor people? Is this greedy person more unjust than some leaders and castle dwellers who shed blood in their fight for power?

"They call it war, and the victors are heroes. Every one of them claims that he is leading a holy war, interpreting God’s words to serve their selfish interest. Everyone shouts: 'We are not the same! Our dead are in heaven and yours are in hell.'" In the denouement of Fire and the Phoenix, we find two human beings exhausted by the complexity of life: Abd al-Rahman, the sultan, and Badr his servant.

The tone of their conversation betrays scepticism and nihilism. Abd al-Rahman asks if it was worth the trouble to persevere on the path of power. Now that he has experienced power stripping him of his human feelings, he bears no grudge against the Abbassids, who destroyed the "Umayyad house" in the east. Basically, they did nothing but quench their thirst for power, he repeats to himself.

Laden with meaning

When Abd al-Rahman was hiding from his persecutors, sheltered in a farm by people who did not then know he was a prince, he heard the son of his host saying: "I don’t regret those who departed, nor do I rejoice over the newcomers. They are all the same. He who was killed is not better than he who killed him; for, had the former had the chance to get to his enemy first, he wouldn’t have hesitated to kill him."

When his father spoke to temper his words, the youth insisted: "This is not what the sultans believe in, even if they were caliphs. They follow their whims and personal goals, then they say it is God’s rule. Each of them interprets God’s rule according to his wishes… the sultan is the sultan… it doesn’t make any difference if he is an Umayyad or Abbasid."

Fire and the Phoenix is less a novel about the past than about the present Arab world. The dubitative tone of the sultan, his silent gaze at his servant, while leaving the place of their last encounter with a feeling of an unbridgeable chasm between them, and the sentimental longing for a bygone symbiosis, aroused by the hearing of Badr’s mellifluous whistling, are laden with meaning. They are meant to remind us of the rift at the origin of the discontent in the present Arab reality.

In light of the inherited political culture and the concomitant structures of power, it is not difficult to understand why the Arab renaissance, conceived as a project that picks up where the ancestors left off, is a thwarted enterprise. The rift between power and people impedes access to modern political culture.

All efforts notwithstanding, and despite all appearances, Arab political life is characterised by constant attempts at harmonising western democracy, predicated on the idea best articulated in Abraham Lincoln’s words as "government of the people, by the people, for the people", and traditional structures of power, which draw their legitimacy from tribe and religion.

Religion, tribe and power

It is undeniable that religion played and plays an immensely positive role in connecting peoples in the Arab world by a power greater than all of them. It grounds this connection in a sort of spiritual space which permits the getting together of tribes, groups and individuals.

However, it is no less true that Arab societies have failed to legislate religious creed into human laws that would outgrow the limits of the past in managing the relationship between the powerful and the powerless, to strike a new balance between the rights of religion and civil authority. It is of the utmost importance to rethink the relation between religion, tribe and power in order to provide political life in Arab societies with a new sense of perspective.

It is of the utmost importance to rethink the relation between religion, tribe and power in order to provide political life in Arab societies with a new sense of perspective

When we read Saif’s Fire and the Phoenix we feel the strong power of words. The novel connects Arab readers with who they are; it grounds their sense of belonging in a past culture that recognises the divine rights of sultans and kings. At the same time, it incites them to overlook the old experiences, in order to avoid the great woes that befell their ancestors. Badr, Abd al-Rahman's faithful servant, initiates a sort of resistance - not to the right of the sultan, be it of a tribal or divine nature - but to the power of the sultan hardening into callous tyranny, which alienates not only its enemies but its servants as well.

Through the character of Abd al-Rahman, Saif highlights a deeply ingrained awareness that unless there is a fundamental shift in the relationship between tribe, religion and power in the course of Arab history, revolution will remain a vain enterprise that bears the seeds of its disruption. While it enables individual men to cast very large shadows of their power, it does not liberate creative energies that are likely to break through the stalemate that grips Arab societies.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.