The Kingdom of Silence: Literature from Tadmor prison

“When death is a daily occurrence, lurking in torture, random beatings, eye-gouging, broken limbs and crushed fingers… [When] death stares you in the face and is only avoided by sheer chance…wouldn’t you welcome the merciful release of a bullet?”

This was taken from a report smuggled out in 1999 to Amnesty International by a group of former Syrian prisoners who had spent years in the infamous Tadmor (Arabic for Palmyra) prison, where unimaginable acts of torture took place against both dissidents and criminals alike.

Tadmor prison fell to the Islamic State group as it captured the city of Palmyra from government forces earlier this week, but the significance of its seizure has been overshadowed by widespread fears that IS could raze the UNESCO World Heritage site just south of the modern town. In fact the capture of the prison could be a much more important development, according to analysts and former inmates of the jail.

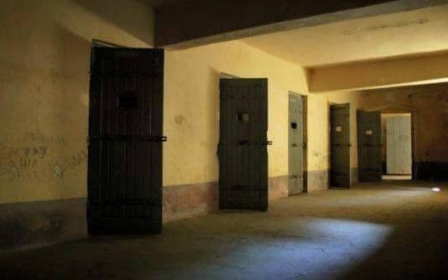

The prison, which used to be a French military barracks, is located in the desert in eastern province of Homs and is around 200 kilometres away from the capital Damascus. As previously reported by Middle East Eye, the massacre of hundreds of prisoners in 1980 after a foiled assassination attempt on then president Hafez al-Assad exacerbated the prison’s symbolic status of repression.

Human rights reports were not the only medium to document what took place in what has been described as one of the worst prisons in the world.

Symphony of fear

The vicious reality of Tadmor, where the blood of those massacred in 1980 was not cleaned up resulting in the mass spread of gangrene amongst the rest of the inmates, created literary works written by survivors and former inmates that narrated their daily lives in stark detail. Whips were given human names, friendships were struck between prisoners and rats and cockroaches, and torture sessions were opportunities to experiment with excruciating devices.

“Tadmor is a symbol of oppression, torture and the dark days of the 1980s,” said Nadim Houry, the head of Human Rights Watch in Beirut to Middle East Eye. “It spawned a genre of literature- a number of former detainees, mostly former leftists and communists, wrote books about their experiences.”

Houry, who interviewed former prisoners and has studied detention centres in Syria, said that Tadmor “was described as the Kingdom of Silence”.

For Bara Sarraj, he called it the “symphony of fear”. Sarraj, who was arrested in 1984, spent nine years in Tadmor prison before being released in 1993.

In a recent interview with the BBC, Sarraj who later studied immunology in the United States, said that torture in Tadmor was “non-stop”.

“You are hanging between death and life,” he recounted. “This is the place that had non-stop executions for 12 years in the yard of the prison.”

Years after his release, Sarraj is writing a yet to be published book titled “From Tadmor to Harvard”, where he narrated the constant, violent beatings and humiliation, as well as the regular hangings that took place.

“Language cannot describe it,” he wrote. “Fear is the internal sensation when you physically feel your heart between your feet and not in your chest; fear is the look on people’s faces, and their darting eyes when the time for the torture sessions comes near.”

Hell of a particular kind

Faraj Bayrakdar, an award-winning poet and journalist, was 36 years old when he was arrested in 1987 and spent 13 years in the Palestine, Saydnaya and Tadmor prisons. He was accused of being a member of the Party for Communist Action, and was released in 2000 after a successful international campaign.

Bayrakdar, who suffered from injuries caused by torture, cannot walk unaided. He now lives in Sweden and in 2010, went back to Tadmor with two other former prisoners, reflecting on their experiences there.

Prior to his arrest, he had published two volumes of poetry: You Are Not Alone (Beirut, 1979) and Golsorkhi (1981).

“The jails of Assad’s regime were a hell of a particular kind,” Bayrakdar said. “Hundreds of thousands of human beings entered this hell. Dozens of thousands died under torture or after military trials which lacked minimum rights, logic and ethics.”

In a poem titled Ode to Sadness, which was written while he was in Tadmor in 1992, Bayrakdar captures the desolation of the prisoners, many of who were left in oblivion to rot in cells.

“Which spirit flutters this night in the sails of

Infinite, or over its masts?

The sand grouse has passed into thought

God passes in sadness,

A distant woman passes,

Silence and meaning pass

And a sail already passed announcing

The journey on a rainy day”

Arab prisoners united in misery

Syria’s prisons were not just open for its countrymen. Many Palestinian, Lebanese and Iraqi men had their share of experiences and tales to tell as prisoners of the overcrowded cells in brutal prisons.

It is believed that hundreds of Lebanese nationals were “forcibly disappeared” in the decades of Syrian control on its smaller neighbour, before the former’s withdrawal in 2005.

The Support of Lebanese in Detention and Exile organisation has complained over many years that successive Lebanese governments have neglected to find out the fate of Lebanese detainees in Syria. Other activist groups have compiled a list of 200 names of Lebanese detainees whom they believe to be in Syria’s prisons, but calls for the Lebanese government to act have been ignored.

With the fall of Tadmor to the Islamic State early on Thursday, local Lebanese media reported that 27 Lebanese prisoners, including some imprisoned since the 1980s, had been released. However, the news is yet to be confirmed.

Ali Abu Dehn, a Lebanese man who was accused of belonging to the Lebanese Forces, spent 13 years shuttled between different prisons in Syria, including almost five years in Tadmor.

Abu Dehn was released in 2000 as part of a series of reformist moves that Hafez’s son Bashar undertook during the first year of his reign. The following year the prison was not shut down as commonly reported, but continued to function as a prison for military soldiers who had committed offences. Tadmor was officially reopened in June 2011 as anti-government protests swept the country.

Punishment for dreaming

Abu Dehn told Al Arabiya channel that the popular saying in Tadmor was that the one who enters disappears, and the one who leaves is newly born again.

“Tadmor prison is one of the worst prisons in the world,” Abu Dehn said. “Upon our arrival, a prison guards told us ‘Hafez al-Assad has forbidden God to enter here. You are all here without God. We are God. We are the ones who will give life to you and take your life away.'”

In his book Return from Hell: Memories of Tadmor and Its Sisters, Abu Dehn wrote about the torture and deaths, and how the prisoners conducted themselves amongst each other and the prison guards. He also wrote about the punishment for prisoners who shared their dreams with one another, especially if it had to do with Syria’s leaders.

In one case, Abu Dehn relays how one prisoner told the others in his cell about how they were all walking at Hafez al-Assad’s funeral, but instead of adhering to a sombre mood, they took the occasion to celebrate and laughed and clapped during the funeral procession.

One of the prison guards overheard the conversation, and the prisoner was taken away and whipped three hundred times.

Another prisoner dreamt that a wolf entered the presidential palace and left with one of Assad’s sons between its jaws. Shortly after he told the other prisoners about his dream, the news broke that Hafez’s eldest son Basil, who was groomed to take over his father’s reign, was killed in an road incident. The prisoner who had the dream was punished severely.

Reliving the pain

Bara Sarraj confessed that it was no easy task to write about the years he spent in Tadmor.

“To write the details… I found out it very hard,” Sarraj told Middle East Eye. “When I look back [I realise] it took three years to write one hundred pages.”

“I understand why other prisoners are not willing to do so,” he added. “You have to live it again.”

Sarraj’s book, which he wrote during his commute to and from work, will be published by Amazon within the next few months. He is in touch with former prisoners, around 60 or 70, through a Whatsapp group, and is keen on documenting all of the executions and their dates they took place in the prison, calling it a “collective memory” effort.

Regarding the latest events unfolding in Syria, Sarraj dismisses the Syrian government as “gangsters” who are “not in consideration anymore”.

“We are optimistic but the future is uncertain,” he said. “Islamic State taking over Tadmor is not a good thing. The antiquities are in danger but human life is more important here.”

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.