'Living hell': New EU-Libya migration plan may be illegal, says UN

The EU’s plans to help Libya stem migrant departures will mean more children being sent back to the country’s squalid detention centres, the UN and rights groups said on Friday.

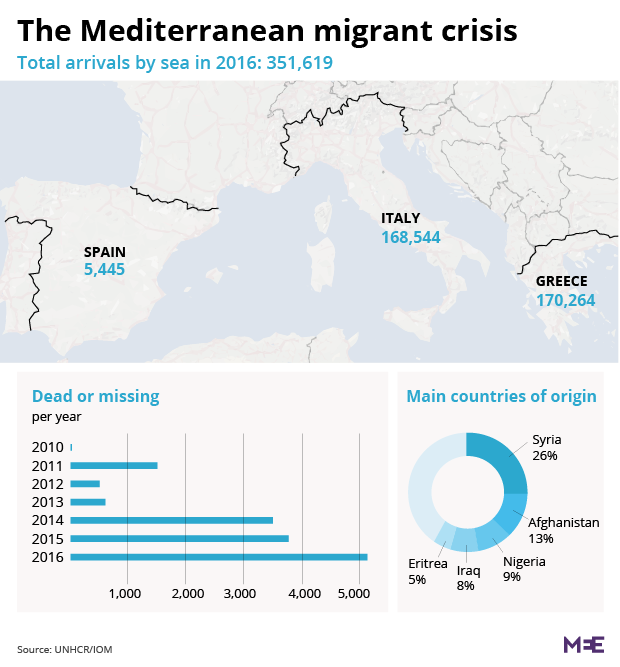

At a summit in Malta, European Union leaders on Friday approved a new strategy to "break the business model" of traffickers, who have helped more than half a million mainly migrants – mostly from Africa - enter the European Union via Libya in the last three years.

The plan, called the Malta Declaration, stresses that the EU will "reinforce return capacities" while respecting international law - the UN, however, has warned that the EU may break international law by returning people to face torture and inhuman treatment in Libya.

NGOs said the plans will mean women and children being returned to inhumane conditions in detention centres where they would be vulnerable to rape, beatings, forced labour and forcible repatriation to uncertain fates in their home countries.

READ: Abused, pregnant and behind bars: Former IS slaves in Libyan prisons

"Sending children back to a country many have described as a living hell is not a solution," said Ester Asin of British charity Save the Children.

The cornerstone of the plan is to fund and train the Libyan coastguard, making it better able to intercept migrant boats before they reach international waters, according to a draft statement seen by AFP.

Libya is still in a chaotic, conflict-scarred state, and a fledgling UN-backed national unity government controls only sections of the country's vast coastline.

In this context, the prospect of turning boats around is causing concern in some quarters.

Human Rights Watch said the EU would be flouting its international obligations by "outsourcing responsibility" for the migrants to a government that is just one party to the conflict in a fundamentally unstable state.

READ: Driven mad: Inside a Libyan detention centre for female migrants

"What the EU wants to call a 'line of protection' could in reality be an ever-deeper line of cruelty in the sand and at sea," said Judith Sunderland, deputy head of HRW’s Europe and Central Asia team.

The UN's refugee agency, UNHCR, and the International Organisation for Migration put out a joint statement on Thursday decrying the "deplorable conditions for migrants and refugees in Libya," saying Libya could not be considered a safe country for refugees and asylum seekers.

"We believe that, given the current context, it is not appropriate to consider Libya a safe third country nor to establish extraterritorial processing of asylum-seekers in North Africa."

The UN's human rights agency, OHCHR, also put out a statement on Friday saying it is concerned that the EU's deal with Libya would push people back to places where their human rights are violated, which would break a fundamental principle of international law.

"Any engagement with third countries needs to be in line with international human rights standards. The EU member states cannot balk from their responsibility and are accountable for any human rights violation under such an agreement," said the UN body.

'Shot like dogs'

The EU's attempts to get Libya to effectively blockade its own coastline follows a record year for arrivals in Italy (181,000 in 2016) and the deadliest winter yet in the Mediterranean, with migrants perishing at sea at a rate of 15 per day over the last three months, according to UNHCR figures.

Rescuers say the death toll has risen because traffickers are sending more and more overcrowded, unseaworthy vessels to sea in tough winter conditions in order to maximise profits while they can.

Critics of EU efforts to resolve the crisis say the Italian-led search-and-rescue operation in the international waters off Libya encourage traffickers because they know they only have to get their human cargo a few miles offshore and they will be picked up and taken to Italy.

Nearly 2,000 rescued

More than 1,750 migrants were rescued in such circumstances on the eve of the summit, when Italy announced its own deal to provide more money, coastguard training and equipment to Libya’s UN-backed Government of National Accord.

The EU's new plans have drawn comparisons with Australia's controversial hardline approach of turning migrant boats away.

READ: Trump and EU are two sides of same coin when it comes to refugees

Migrants on board the Aquarius, a rescue boat chartered by France's SOS Mediterranee, described the prospect of being returned to Libya as horrifying.

"The Libyans shoot us like dogs," Boubacar, a 17-year-old Guinean was quoted as saying by a spokesperson for the charity.

The UN's children agency UNICEF said an unprecedented 1,354 migrants, including 190 children, had died in the Mediterranean in the past three months.

The vast majority of them perished on the Libya-Italy route and the death toll was 13 times higher than in the same period in 2015-2016, the body said.

"The decisions taken at Friday’s summit could literally mean the difference between life and death for thousands of children transiting or stranded in Libya," said UNICEF deputy executive director Justin Forsyth.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].