Fading hopes for Egypt's revolutionary cycle

Twenty-five-year-old lawyer Karim Mohamed remembers the walk down the Nile Corniche to Tahrir Square on 30 June last year as crowds marched against Mohamed Morsi. "People were gathered together in one opinion to take down the Muslim Brotherhood," he says. "When I went to the streets on 30 June, I wanted to end the Brotherhood era and to have a better country – as all Egypt wanted."

Once Mohamed reached the square, things were a little less clear. Army helicopters circled overhead and police officers were seen inside Tahrir – an almost alien concept after the 25 January revolution in 2011.

"The first mark of depression I felt was when I saw the people cheering for the army," he said. "I saw some of the protesters holding police officers on their shoulders."

While history was being made, Mohamed said, he also felt suddently that it was being repeated. "To witness this in the place where we got rid of the old regime… I cannot express my feelings. I felt… defeated. This time the people were chanting for the government."

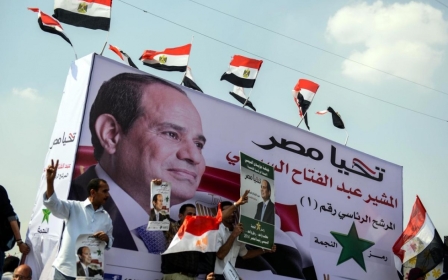

One year after the mass protests spearheaded by the Tamarod ("rebellion") campaign against Mohamed Morsi, and his 3 July overthrow precipitated by Abdel Fattah al-Sisi's military takeover, Egyptians are still divided over exactly what happened and what it means for the country's future.

On the evening of 3 July, Sisi appeared on television to announce that President Morsi was gone. The army's 48-hour ultimatum had passed without any offer of compromise from the Islamist leader, he said.

"As the armed forces cannot just turn a deaf ear and a blind eye to the movement and call of the Egyptian people, they have invoked their patriotic, and not political, role," the army chief was quoted as saying, flanked by religious and political figures.

In Morsi's place, Sisi said, Egypt would have a "transitional roadmap" guaranteeing a new constitution and committee for national reconciliation, as well as paving the way for presidential and parliamentary elections.

While Morsi supporters and Islamists planned their next move, Tahrir erupted.

Anhar Wafa, a middle-aged woman from Saft al-Leban village in Giza, now wishes she had gone down to Tahrir that night.

"I thought Sisi was the savior of the people," she remembers. "I was hoping this would happen. I was waiting for someone strong to save Egypt from a dangerous situation because Morsi was leading us to civil war."

Many Egyptians agreed: according to a much-cited Zogby poll from the month before, the army had scored a 94 percent confidence level. Some 60 percent of non-Islamists polled said they supported a temporary return to military rule.

Wafa believed that the Brotherhood aimed to kill opposition figures and promote extreme, conservative religious ideas in Egyptian society.

"I felt safe when the army announced it was going to protect us against them," she says. Liberal and revolutionary groups criticized the Brotherhood for betraying the revolution and attempting to consolidate its power over the rest of the country.

To the outside world, 3 July carried all the hallmarks of a military coup – tanks on the streets, men in military uniforms giving grand, patriotic statements through the television, the removal of visible opposition. And yet the majority of non-Islamic Egyptians supported it.

Sisi's 26 July popular mandate to "confront violence and terrorism" (words then reasonably interpreted as meaning the Brotherhood), the Rabaa al-Adaweya dispersal and the ensuing crackdown against Islamists, secular activists and, increasingly, any expression of free speech that counteracts the authorities' narrative, have all in their own way altered the legacy of 3 July – Or Egypt's "corrective wave of the 25 January revolution", a commonly heard phrase among officials, in Sisi's speeches and the public in the past year.

'The longest day of my life'

Pro-Morsi engineer, Abd El Rahman Refat, says the army "stepped over the people's desires". There is no doubt in his mind that 3 July represented a military coup.

Refat spent much of his time in Rabaa al-Adaweya in the days and weeks after 3 July. Despite rising tensions and a series of street massacres conducted by the security forces, Refat kept going back.

"My family was trying to stop me from going, but I couldn't stop," he said.

For Morsi's supporters, Rabaa became the bastion of legitimacy.

And yet for over a month allegations surrounded the camp – torture and the harassment of anti-Morsi locals; sectarian rhetoric bellowed out from across the sit-in's stage; the concealment of terrorist elements and weapons. So too did the looming threat of a major security operation to clear it.

"Before they cleared the sit-in, we thought they wouldn't do it. I was with so many people there and then all of a sudden I was seeing them get killed," Refat said.

Estimates suggest around 1,200 people died.

Refat went to Mostafa Mahmoud Square in west Cairo's Mohandiseen district. Brotherhood supporters from a sit-in in Nahda Square had marched to the mosque there, and by midday intense fighting with police, thugs and locals were underway. Journalists reported seeing a handful of men with guns amongst the anti-Morsi crowd. The police responded by killing over 20 people. "We saw the police firing at the people; so many injured people and dead bodies everywhere… It was the longest day of my life."

Nahda Square is next to Cairo Uni on the opposite side of the Nile from Rabaa al-Adaweya - they're probably about at least half an hour away from each other by car.

'Human rights crisis'

A year after 3 July, the once all-encompassing polarisation and coup-revolution divide between Islamist and army supporters has taken a back seat as Egyptians react to new circumstances. Economic renewal and combatting a wave of terrorism that has left hundreds of police and army officers dead in Sinai and beyond are the government's priorities now. Meanwhile, a security crackdown estimated to have imprisoned between 16,000 and 41,000 people continues to spread through society with abandon.

Human rights groups now say they are navigating their way through a period of unprecedented repression and rights abuses, recently described in a joint statement by Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International as a "human rights crisis." One Amnesty representative claims there are still signs of cooperation with state-founded rights organisations, but that abuses are still going on.

"Amnesty International has shared concerns on ongoing torture and enforced disappearance with the 30 June Fact Finding Committee [established to investigate post-30 June violence], however until now we still hear of persons arrested and held in secret detentions where they are subjected to torture with no access to the outside world," says Peter Splinter, Amnesty's Representative to the United Nations in Geneva.

Stories of torture, forced disappearances and impunity among the security forces are common. As well as thousands of Brotherhood leaders and supporters, leading secular activists such as Alaa Abd El Fattah, April 6's Ahmed Maher and Alexandrian leftist Mahienour al-Massry are now all in jail. The Guardian recently conducted an investigation into the Azouly military prison in Ismailia, where 400 people are believed to be held incommunicado and exposed to horrific torture practices. No member of the security forces has yet been punished for their role in the violence.

"If Egypt’s 30 June National Fact Finding Committee does not deliver effective, independent and impartial investigations by September 21 in violence post-June 30 and brought those responsible to justice, the mechanisms of the Human Rights Council should be used to pursue an international investigation," Splinter adds.

'I see hope in the near future'

While international attention focuses on the detention of journalists and ordinary Egyptians, Sisi's supporters still have their qualms – despite supporting the overall direction Egypt is headed.

Wafa, for example, criticizes the Protest Law, which forbids public gatherings of more than 10 people without approval by the Interior Ministry. "I saw that he came to power through protesting and now he wants to make protesting forbidden? I hope he removes this law or maybe removes it eventually," she says, adding that recent economic initiatives – a LE1,200 (US$167) minimum wage, an apparent reduction in the president's salary and cheap prices during Ramadan – Sisi still presents hope.

Most people accept that the economy will be Sisi's crucial challenge. Activists and analysts suggest it could be a major fault-line in the future, should he fail. "But with all the other projects I've heard about in the media, I see hope in the near future," Wafa adds.

For many Islamists and young people who identify with the January 25 revolution, the future couldn't feel more different.

"Personally, I'm always afraid," Refat says. "I can't respect the people in Egypt anymore. Mosques are getting controlled by the government and there is no freedom."

"I wish the people understood," he adds, disconsolately.

Karim Mohamed, the 25-year-old lawyer, believes the events of last year are not over. One year of history will last a lot longer.

"We tried to finish the Brotherhood, but that doesn't mean we wanted the army back in power," he says. "It seems like an endless circle we will have to fight for the rest of our lives."

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.