I was force-fed by Israel in the '70s: This is my story

As Palestinian hunger striker Mohammed Allan has entered a coma and precariously hovers between life and death, the Israeli Medical Association (IMA) continues to refuse to force-feed him.

The ability to force-feed hunger striking prisoners has always existed within Israeli prisons, but it was only authorised legally on 30 July when the Israeli parliament, the Knesset, voted in favour of in a 40-46 majority.

Arguing that it contravenes legal and ethical regulations, the IMA is challenging the law in Israel’s High Court, vowing to “do everything to prevent its implementation".

Yet back when it was used as a form of torture against the first mass hunger strikes among Palestinian prisoners, there was little opposition from any Israeli side, even when it resulted in the death of three prisoners.

Welcome party to appalling prison conditions

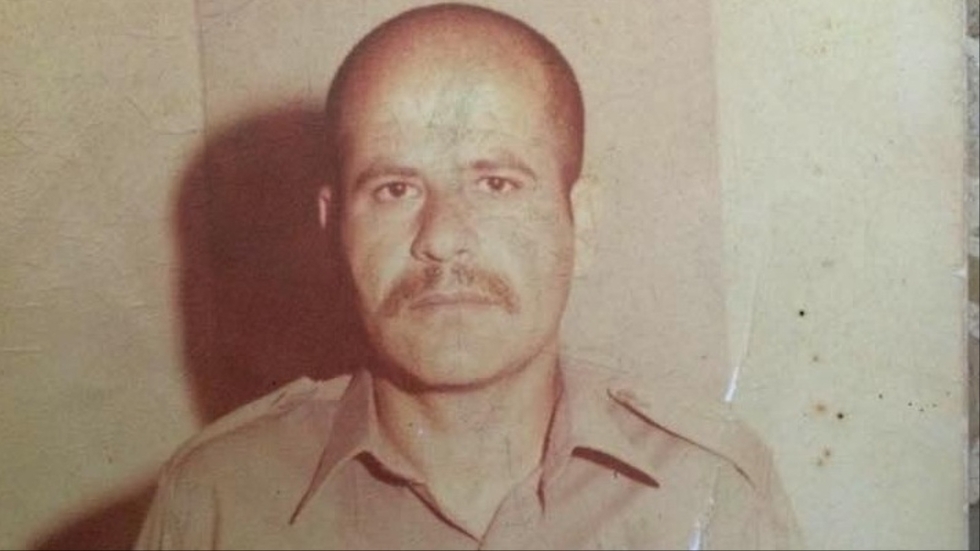

Mousa Sheikh, a 69-year-old former prisoner from the village of Aqraba in Nablus, participated in the first mass hunger strike in 1970 and again in 1976. Describing prison conditions back then as “no better than the Bastille or the Auschwitz Nazi camps,” Sheikh painted a forbidding reality of the environment that engulfed prisoners in Israeli jails.

“The Israeli prison services back then would receive any new prisoner by shaving his head, followed by a welcome party,” Sheikh told Middle East Eye. “He would be encircled by a group of soldiers who would beat every inch of him in the most savage way, leaving the prisoner in a bad state before finally going to his cell.”

Sheikh, who now lives in Ramallah, was arrested at the age of 21 in 1963 after engaging in an armed confrontation with the Israeli army. Five of his comrades were killed, and he was given three life sentences plus an additional 20 years. He was transferred from Nablus Prison to one in Ashkelon, where conditions were so dire that in 1970, 400 prisoners were motivated to launch the first hunger strike.

“The food was terrible, and very limited. We only got 150 to 200 calories a day. There was barely any recreation time,” Sheikh said.

The prisoners’ demands were basic. They asked for more outdoor time, better quality and quantity of food and access to books and magazines.

The strike barely lasted for one week, and none of the demands were met. According to Sheikh, the prison warden told them that the Israeli government ordered the prisoners to be humiliated every day, because their hands were stained with blood. The force-feeding began almost immediately.

Dancing from pain

Described as a dangerous procedure, force-feeding violates a prisoner’s right to hunger strike as a form of protest by feeding them intravenously, bypassing the usual process of eating and digestion.

The act involves inserting nasal tubes, sometimes over a metre long, until it reaches the hunger striker’s stomach. There’s the threat of the tube missing the stomach and entering the lungs, which is fatal. Nutrients or liquids are then administrated through the tube for an hour or two.

“The prisoner enters the room handcuffed and legs shackled,” Sheikh said, recalling force feeding at the prison in Ashkelon.

“There are two police officers on either side of the prisoner, who terrorise him physically and mentally. They poke him harshly in the ribs and on the back of the neck, talking the whole time in a way that is meant to break the prisoner’s spirit, saying things like ‘you are practically dead now.’ The prisoner is tied to a chair so that he can’t move. The doctor then sticks the tube up the nose of the prisoner in a very harsh way," he said.

“When it was done to me, I felt my lungs close as the tube reached my stomach,” Sheikh recounted. I almost suffocated. They poured milk down the tube, which felt like fire to me. It was boiling. I could not stay still and danced from the pain. I danced a lot.”

Sheikh said that the prisoners were all subjected to the painful procedure until his cell mate, Abd al-Qader Abu al-Fahm, died as a result. Abu al-Fahm was a fighter from Gaza, and when he was arrested he suffered from 32 injuries that were not treated by the prison hospital, according to Sheikh.

“The rest of the prisoners tried to convince him not to go on strike since he was injured,” he said. “But he didn’t have any of it and said, ‘I am as you all are. I cannot eat while you all hunger strike’. The doctor who fed him the tube also applied so much pressure to his stomach that it caused his death from internal bleeding.”

Deaths caused by force-feeding

Conditions in the prison grew worse over the years, Sheikh said. Physical torture was used regularly. This culminated into the second hunger strike in 1976 that lasted for 45 days, undertaken by around 500 prisoners.

Force-feeding was also used, and different prisons exercised various methods. In Nafha Prison in the Negev desert, for example, tubes were inserted in the mouths of prisoners.

In 1980, around 1,000 prisoners participated in a third mass hunger strike. There was no reprieve from the force-feeding though, which resulted in the deaths of three prisoners: Ali al-Jafari, Rasim Halaweh and Ishaac Maragheh.

Sheikh himself was released in a prisoner swap in 1983, and exiled to Algeria. He came back to the West Bank after the creation of the Palestinian Authority (PA) in the early 1990s, after the end of the First Intifada.

Prison conditions gradually improved after the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993. Prisoners were placed into cell divisions based on political affiliation, and some were internally appointed to act as the representatives of prisoners that dealt with the Israel Prison Service. Education was also permitted.

Ending a prisoner’s protest against his will

In recent years, however, individual hunger strikes by prisoners who have not been formally charged with anything and spend months, if not years, languishing in jail have become more frequent.

Administrative detention, which follows a form of internment used by the British from the Mandate-era days, has been extensively used by Israeli authorities currently and over the past decades against Palestinians.

The detentions allow Israel to hold a suspect indefinitely and without trial or charges levelled against him until the state has gathered sufficient evidence. The detentions are used almost exclusively on Palestinians. Administrative prisoners strike not for better conditions, but simply for the right to be charged or released.

Several high-profile hunger strikers, like Khader Adnan and former football player Mahmoud Sarsak, have raised the issue of administrative detention on an international level, with human rights organisations like Amnesty International condemning its use as illegal.

Sheikh acknowledged that the focus should be on administrative detention, and how force-feeding is a way for the Israeli state to coerce prisoners into not exercising their right to protest.

“Administrative detention violates international law,” he said. “The 1949 Geneva convention stipulates how an occupying power must treat prisoners accordingly. But Israel sees itself as above any law and follows its own legislation. It keeps repeating, like a broken record, how it is the only democratic country in the region but it does not implement any of the international laws.”

Absence of popular support maintains status quo

Sheikh says he still suffers from health repercussions in his heart and lungs as a result of force-feeding. The medical staff at Barzilai Hospital, where Mohammed Allan has slipped into a coma after experiencing epileptic seizures following 60 days without food, have hooked him up to saline and glucose drip to stabilise his condition.

This has angered his family, who are torn between keeping Allan alive and respecting his wish to remain on hunger strike. Yet observers say the willpower of one man will not change Israel’s policy against him; a popular movement that applies pressure to both the PA and Israeli government is seen as essential to tip the scales into Allan’s favour.

“When we passed our 30th day of hunger strike in 1976, there was almost an intifada,” Sheikh said. “But no one talks about that. In all of the main Palestinian cities and towns, there was a massive popular onslaught of protests.”

“The Israel Prison Service realised the amount of pressure that they were under and sought to defuse the situation, so they granted us our demands, thus ending the hunger strike.”

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.