Lewis Hamilton and the battle for Formula One's place in the Gulf

Bernie Ecclestone, the man who ran Formula One for four decades, is recalling the deal that took the motorsport to Bahrain in 2004.

“When we first went there we had a bit of trouble with the local people, who were upset about what they thought the rulers were doing,” the 90-year-old British business magnate tells Middle East Eye.

“In the end, I met all the protesters and really sat with them and talked to them. I said to them at the time, ‘What you’re looking for is a revolution, really’. That’s what normally happens. And then you attack the crown and capture the country. I said that’s the only thing you can ever do.”

Ecclestone wasn’t expecting Bahrain’s barricades to be stormed, though. “I mentioned that was what would normally happen when these things happen, knowing full well there was no way in the world it could happen because they would never be able to do that.”

Speaking from his home in the Swiss Alpine resort town of Gstaad, Ecclestone says he used to travel to Bahrain “without all the so-called bodyguards,” meeting opposition groups and the kingdom’s rulers at his hotel.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

The idea for staging a race had come from the island kingdom. The Cambridge-educated Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa became Bahrain’s crown prince in 1999, a few months before his 30th birthday.

Salman got in touch with Ecclestone, who found the young royal to be a “very nice person” and a “very good leader”.

“He was completely behind this because he realised that it would be the best thing that could happen for the country,” says Ecclestone. “It was a case of pointing out what was best for everyone.”

On this, Bahrain’s ruling Khalifa family and the F1 supremo were aligned. Hosting a Grand Prix would put the kingdom on the map, open it up to foreign investment and make it a more attractive destination for tourists.

For the motorsport, it meant new revenue streams in the wake of the loss of sponsorship from tobacco companies and expansion into the Middle East, which had never hosted a race.

“We’d been calling ourselves a world championship for years, and we were a European championship,” says Ecclestone. “I thought Bahrain would be great. It’s another part of the world. Normally people would have no reason to go there. So we’ve opened the door for people doing business... Using the sport to open doors that probably would never have been opened.”

Construction of the Bahrain International Circuit in Sakhir began in 2002 and cost $150m. The first race took place on 4 April 2004 and was won by Michael Schumacher, driving a Ferrari.

“Nobody believed there was ever going to be a race in that part of the world,” says Ecclestone. “Bahrain had the courage to do it. I said to the crown prince – he’d opened the door to the Middle East countries – we won’t race anywhere without your blessing. So when it was the case of meeting Abu Dhabi to discuss everything there, I said to them you have to get the okay from Bahrain.”

By May 2007, Abu Dhabi was building a race track of its own. The Yas Marina Circuit cost $1.3bn and involved the creation of a manmade island. Like the circuit at Bahrain, it is, F1 insiders say, the best of the best, complete with top-of-the-line facilities.

'It suited us and it suited them. You have to pay the price for that. They realised it was cheap anyway for the amount of publicity they got'

- Bernie Ecclestone

Ecclestone was very impressed when he first met the “charming” Mohammed bin Zayed, Abu Dhabi’s crown prince, who had initiated talks about bringing F1 to the emirate. The two men had dinner at an outdoor restaurant with two others, whom Ecclestone identifies as bin Zayed’s “right-hand man” and “somebody”. No bodyguards were present.

“When we left the restaurant we walked to a car, he [MBZ] drove the car himself and was just very, very normal, nice people, not trying to impress anyone; that’s what I liked more than anything.”

The F1 chief told bin Zayed it would be very difficult to have a street race in Abu Dhabi because of the US-style grid system in the city.

Bin Zayed told Ecclestone not to worry, that they’d build an area big enough to put a racetrack on. “I said fine, that would be super but you understand how difficult that would be – and what did they do? They built the island. If somebody said that to you, you’d probably think: ‘What are they talking about?’”

What appealed to the F1 man was the way rulers in Bahrain and Abu Dhabi did exactly what they said they were going to do. Ecclestone happily acknowledges that he thinks one of Europe's big problems is “too much democracy”. He is a friend of Russian President Vladimir Putin, who he describes as a “nice, nice, nice person,” as well as a formidable leader.

“He's another one of these guys that do exactly what they say they are going to do,” Ecclestone says, drawing a direct link between Putin and the Gulf kingdoms. “They don’t change their minds halfway. They make it work.”

At the same time as Abu Dhabi’s circuit was being constructed, in 2008, Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed, an Emirati royal, bought Manchester City Football Club. “They had opened their eyes to sport, they could see that Formula One was good for them, and they could see the connection,” Ecclestone says.

“They’ve become very much part of the world now, whereas before they were very isolated.”

For Ecclestone, it was a win-win situation. “Financially, the people we are dealing with in this part of the world value things differently than the people who have been around for years,” he says.

The sport makes much more money from races in the Middle East than it does from those on circuits such as Monaco and Silverstone, which are known around the world and whose tracks hold the history of racing deep in their tarmac.

Speaking about F1 and the Gulf kingdom’s rulers, Ecclestone says: “This is what you wanted to do, to use the brand to promote the country, which is what they wanted to do obviously. It suited us and it suited them. You have to pay the price for that. They realised it was cheap anyway for the amount of publicity they got. We all knew exactly what we were doing. And by luck, I think, it worked out all right.”

This season, the first Saudi Arabian Grand Prix will take place. It is the first Grand Prix whose deal was not done by Ecclestone. But without those dinners at hotels in Bahrain and Abu Dhabi, it would never have come to pass.

The Bahrain opener

This Sunday’s season-opening Grand Prix in Bahrain will take place a decade after F1 cancelled the race, after the government crushed the 2011 protests that rose up in the wake of the Arab Spring.

It is an event that sits at the heart of a debate around “sportswashing,” or the use of sporting events by governments and large corporations to burnish their brand, build soft power and deflect attention away from all manner of abuses.

Back in 2011, dozens of protesters calling for democratic change including an elected prime minister and a constitutional monarchy were killed and thousands arrested. Among their number was Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, who is now the director of advocacy for the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (Bird).

F1 returned to Bahrain the following year, but popular protests against the race have continued. “Desperate to project an image of normality to the world, Bahrain police have routinely suppressed these protests with violence,” says Alwadaei.

Assaulted, tortured and imprisoned

In 2012, Salah Abbas was shot dead by police at a protest on the eve of the Grand Prix. That same year, Alwadaei says he was shot by police with birdshot and tear gas for joining similar anti-F1 protests. He left Bahrain and became a refugee in the UK. Three years later, his Bahraini nationality was revoked. The human rights activist remains a stateless person to this day.

Like Alwadaei, Najah Yusuf has personal experience of the direct link between Bahrain’s ruling class and Formula One. In 2017, the then-civil servant and mother-of-four criticised F1 and the Bahraini government in a Facebook post, with the court judgement against her saying she had written that the Grand Prix was “nothing more than a way for the al-Khalifa family to whitewash their criminal record and gross human rights violations”.

Yusuf says she was assaulted, tortured and imprisoned for three years following the post, with officers at the Muharraq police station beating and threatening to rape her until she signed a prepared confession.

The Bahraini activist told a virtual press conference organised by Bird that, thanks to international pressure, she was released in August 2019 and that soon after the UN declared her detention arbitrary and called for her to be compensated.

“My only offence was posting criticism of F1 on social media,” Yusuf says. “In Bahrain, it’s enough to see you tortured and thrown in jail for years.”

'I’ve lost faith that F1 will ever help me get justice. For us Bahrainis, this is about more than just a motor race'

- Najah Yusuf

She maintains that, while F1 promised to help her, they have done nothing. “I continue to face harassment from Bahrain’s government because I refuse to remain silent about my ordeal.”

More than that, Yusuf’s son Kameel Juma Hasan was arrested when he was just 16 for taking part in opposition demonstrations and now faces up to 27 years in prison. Amnesty International has called his arrest a “reprisal against him and his family after he and his mother refused to become informants and his mother spoke out in the international press”.

Since the UN ruled that her detention was arbitrary, F1 “has made no attempt to meet me,” says Yusuf.

“I’ve lost faith that F1 will ever help me get justice. For us Bahrainis, this is about more than just a motor race. This is about companies coming to Bahrain and giving the government a stage to show how modern and progressive they are, while protesters are shot down in the streets.”

In 2015, F1 formally adopted a human rights policy for the first time. At the Bird press conference, it was clear that Bahraini activists felt that while the policy had promised to herald a new dawn, six years on it wasn’t working.

“Until today, we are still seeing protests against F1 violently suppressed and critics of the race thrown in prison, while F1’s management bury their heads in the sand,” said Alwadaei.

Hamilton speaks out

While Bahrain’s activists are giving up on F1’s management to help their cause, some have looked instead to seven-times world champion Lewis Hamilton, who has begun to speak out on issues of human rights and racial justice.

Born in 1985 in the English town of Stevenage, Hamilton is the first and only Black driver to race in F1. A go-karting prodigy, he was signed to the McLaren young driver programme at the age of 12, going on to finish runner-up in his first F1 season in 2007, aged 22.

Having effectively turned professional as a teenager, Hamilton’s childhood was far from normal. “I was groomed and restricted and felt that was the only space I was allowed to be in,” he once told GQ magazine.

He was surrounded by PR people, told what to wear and told what to say. Ron Dennis, the man who ran McLaren for decades, was known to strictly control what his drivers did and did not say. Dennis became so well known for finding complicated ways of saying almost nothing, that the term “Ronspeak” was coined. It was a mode his drivers, Hamilton included, sometimes dropped into.

In September 2012, Hamilton shocked the racing world by announcing that he was leaving McLaren for Mercedes.

“It was only then that I started to make my own decisions in life,” he said. The greater freedom afforded to him by Mercedes has seen him embrace a jet-setting lifestyle.

He lives in the tax haven of Monaco and parties around the world, pictured alongside Rihanna, Rita Ora and Nicki Minaj. He’s making an album. He owns a massive ranch in Colorado. In return, Hamilton has won championship after championship for Mercedes.

At the same time, the once shy boy obsessed with motor racing has begun to go through what one F1 insider described as a “more typical adolescence”.

This has included a public political awakening of sorts. The murder of George Floyd, a Black man, by US police in May 2020, left Hamilton “overcome with rage”. He has made his support for the Black Lives Matter movement public, taking a knee and wearing a BLM t-shirt on the starting grid before races.

On 11 June 2020, Hamilton posted a reading list on Twitter that included Malcolm X’s autobiography, Alice Walker’s The Colour Purple, and There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack, the first book by the renowned Black British academic Paul Gilroy.

“I don’t think Lewis has read the book – no disrespect to him,” Gilroy tells Middle East Eye. “The thing about that book is that because of the title, it’s always attracted a certain interest that it doesn’t really merit... People are always rather shocked if you tell them that it was a National Front slogan that people chanted at cricket matches and so on. I don’t mind him telling people they should try and read it – good luck to them.”

'I don’t think we should be going to these countries and just ignoring what is happening in those places, arriving having a great time and then leave'

- Lewis Hamilton

Gilroy sees Hamilton’s activism as “more interesting as an example of celebrity – the sort of power of celebrity in that moment and the particular kind of celebrity he is.

“I’ve not watched the video of George Floyd being murdered, but I’m sure Lewis has, and if it woke him up then so much the better,” Gilroy says.

“I’m not going to complain if the appalling shock of that murder wakes him up and alerts him to the - dare I say it - responsibilities that follow from the kind of visibility and celebrity that he has acquired. If that happens, then that’s got to be a good thing.”

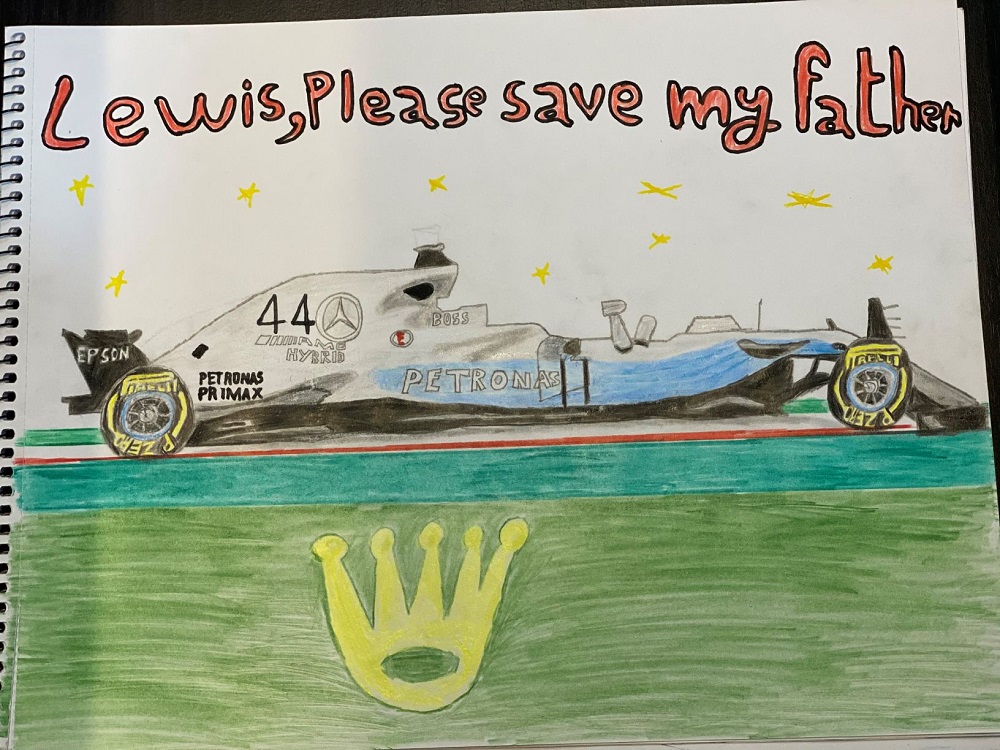

Hamilton’s support for Black Lives Matter has been followed by a willingness to listen to Bahraini activists. At the press conference organised by Bird, 11-year-old Ahmed Ramadhan described how, for most of his life, his father Mohammed had been on death row in Bahrain, after he was convicted of murdering a policeman.

Amnesty International has called Mohammed’s trial “grossly unfair,” and it is widely alleged that the conviction was based on confessions extracted by torture. Mohammed Ramadhan is a member of Sunni-led Bahrain’s Shia community, and his arrest came in the wake of anti-government protests. Ahmed was four years old the last time his father picked him up from school.

Last year, Hamilton read a letter from Ahmed’s father. “I was so excited,” the 11-year old said. “He’s my favourite driver ever, and I always drive as him on my Real Racing game, so I drew a picture of his car for him.” Ahmed’s father saw the drawing on the news and told his son how proud he was of him.

At a press conference on Thursday evening, Hamilton was asked about the letters he received from Bahraini torture survivors before last year’s race. The driver said the letters had “weighed quite heavily one me,” and that it was “the first time I’d received letters like that”.

Hamilton says he has met the British ambassador in Bahrain and has spoken to Bahraini officials.

“At the moment, the steps I’ve taken have been in private, and I think that’s the right way to go about it, so I don’t want to jeopardise any progress,” he said. “But yes, that’s the position we’re in now, and I’m definitely committed to helping in any way I can.”

Hamilton continued: “In terms of whether it’s Formula One’s responsibility, I don’t know if that’s for me to say... But I don’t think we should be going to these countries and just ignoring what is happening in those places, arriving, having a great time and then leave.”

A spokesperson for the FIA, Formula One's governing body, told Middle East Eye:

"We have always been clear with all race promoters and governments with which we deal worldwide that we take violence, abuse of human rights and repression very seriously.

"Formula One's human rights policy is very clear and states that the Formula One companies are committed to respecting internationally recognised human rights in its operations globally and have made our position on human rights clear to all our partners, including the drivers, as well as the host countries who commit to respect human rights in the way their events are hosted and delivered."

The Bahraini embassy in London did not respond to Middle East Eye’s request for comment.

'They'd [F1 owners] only be interested if it was politically difficult for them and if their share price dropped'

- Bernie Ecclestone

Bahrain's government has previously said that it "has a zero-tolerance policy towards mistreatment of any kind and has put in place internationally recognised human rights safeguards”.

“They don’t seem to be,” Bernie Ecclestone said, when asked if F1’s owners are worried about Lewis Hamilton’s burgeoning activism. “They’d only be interested if it was politically difficult for them and if their share price dropped.”

Paul Scriven, a member of the British House of Lords who has shown a particular interest in Bahrain, told MEE it appeared that F1’s senior leadership were putting profits before any moral obligations.

That, in part, explains the decision to try to involve Hamilton. He and his fellow campaigners are preparing to put the spotlight on F1’s corporate sponsors and “appeal directly to their consumers”.

For the moment, a lot of hope is being placed in Hamilton. It may not entirely be in vain. British observers need only look to the footballer Marcus Rashford to see what can happen when a sportsman dedicates himself to political activism.

“I was surprised when he took up the issue of what was going on in Bahrain and I was pleased,” says Paul Gilroy of Hamilton.

“I want to leave open the possibility that if the right pressure is applied and if the right conversations are had, something can happen. He’s not as vulnerable as he was on the way up; he’s on the plateau now so he can afford to take some risks.

“If he gets into those conversations, who’s to say that this is the end of it?”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.