The silence of a coward: Why I no longer play the 'good Muslim'

Editor's Note: This essay, published under the title 'The Duty to See, the Yearning to be Seen,' is an extract from I Refuse to Condemn: Resisting Racism in Times of National Security, edited by Asim Qureshi and published by Manchester University Press.

On a cold winter's night, my mother took my brother and me to a hospital on the other side of Berlin. It was the early months of the Second Intifada, when the majority of Palestinians were killed or maimed in demonstrations. I was told Germany had flown in two Palestinian youths who required immediate medical attention.

We entered their room quietly, not to disturb whatever peace was found among flickering lights and pale, dry walls. The older adolescent - 18 years old perhaps, my brother's age - was awake, while the younger one slept in a separate chamber.

I remember the emptiness in the room, and wondered if anyone else but my mother knew of their stay. She stood by the older adolescent's bedside and they conversed. My Arabic was Egyptian-manageable, so I only grasped fragments of a story told in a Palestinian dialect.

My mother, keen as she was of my limitations, translated fragments of the story. The boy in the other room, she told me, was my age - 14. He had been shot in the leg.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Before leaving, my mother pressed a finger to her lips and took us into the other room to witness the sleeping child. A strange assemblage of beams and bandages enclosed his leg. I remember thanking God he was asleep.

I wondered what it felt like to be shot; why anyone would want to shoot a child; what the cost of a leg really was. Most of all, I wondered if it was worth visiting someone who was asleep, in an empty room, with no one to remember the event but ourselves. I realise now that was the point. My mother died suddenly not long after that hospital visit.

My mother taught me the responsibility to see, pitted against our very nature to be seen. When we ask ourselves how we have gotten here, that hospital room's sombre and gazeless silence has always struck me as important.

In a book on the value and refusal of condemnation, my story will ultimately revolve around the angst of being ill-seen or, worse, not being seen at all. It is, then, ultimately a story of cowardice and I write this for those who, like me, are cowards. We must remember that it is only through fear that one learns to be brave.

The focus of this essay, then, is on sight. I draw on my experiences, where the gaze of others constitutes the means and the end of my efforts. My story will be shared in segments, with different moments unveiling different sides of an experience. I will look at that terrible marriage of cowardice and silence, each begetting the other. It is one thing to not condemn, it is another to know that my silence and the fear to "condemn condemnation" is born of an ever-present desire to remain seen.

The marriage of cowardice and silence

My school in Berlin was privileged by its demographics, which were white and middle class. Almost everyone I knew took their education seriously. I was the only Muslim in my year.

Political science was not a course I enjoyed. At the time, in the early 2000s, it was an endless exhibition of the EU and its hegemony, which meant questioning that dreaded potential of Turkey's joining. It was obvious that the subject was of the teacher's choosing. She appeared stuck on the Muslim question, always interrogating the place of Muslims in Western society.

One day, completely out of the blue, my political science teacher requested I stay behind after class. I was unsure what to expect: I would get into trouble for clowning around anywhere, but I was particularly quiet in her class. I waited for the class to empty then, without warning, she approached and admitted she didn't want people like me in her neighbourhood.

I nodded unthinkingly, unsure if it was to bring an end to our interaction or to give her the assurance she sought.

I immediately recounted the experience to my English teacher. We were close and I knew she understood the gravity of the situation. As expected, she turned crimson and ran off, keen, I'm sure, on finding some retribution on my behalf. Whatever she found, I never saw.

So far, my tale is but one iteration of a post-9/11 tale told countless times. It turned otherworldly soon after, however. Frustrated, I shared my story with a Muslim friend outside of school. We rarely spoke and, as fate would have it, he told me his teacher had recently told him the same thing. We laughed about this odd synchronisation of racist teachers across Berlin, and I found solace in the divine coincidence.

Then my friend admitted he punched his teacher in the face.

I was taken aback, unsure of myself. I was angry at my teacher as well, of course, but this emotion had amounted to very little. I felt embarrassed, not because I didn't consider violence as an option, but because this fated phone call inspired a harsh revelation: I may not punch, but I learned it was fear, not good manners, which saw me shirk from conflict.

I felt I was suddenly forced into a conversation with an alternate version of "me" whose dimension split at the moment of injury. A me who didn't bow so quickly to oppression, as unwise and unethical as the fist may be. A me who had the courage and creativity to find retribution, beyond the meagre choices set before me.

My friend surely took notice of my unease and filled the silence. My teacher was a woman, he joked, and after all it was only correct to punch men. I didn't tell him all I knew to do with anger, any confidence I had, was to bottle it in; perhaps arbitrarily displace a portion of it onto an English teacher, which I knew would amount to nothing. I didn't tell him I didn't even have the heart to disagree with my teacher. I didn't tell him I just found out I was a coward.

I waited for the class to empty then, without warning, she approached and admitted she didn't want people like me in her neighbourhood

I wanted to be seen, but I feared the unwelcoming, rejecting gaze, so pronounced in moments of conflict. So, I remained catatonic for the remainder of the two years I had with this political science teacher. I had forgotten the face of my mother by then. She would have reminded me the other's gaze mattered very little.

In the end, political science pulled my marks low. Despite attempts to make up for it in other classes, my final GPA (grade point average) ensured I couldn't enter my programme of choice at any university in Berlin.

Outside of goodness

The question of why it is difficult to refuse condemnation misses the wood for the trees. My self-interrogation would rather invert the question on its head: why is the approval of others so alluring? For Muslims across the Global North, the want to condemn terror is salient, but it is only one account of a want to be seen.

The war on terror needs no introduction, but insofar as it reflects a dynamic process - fluid, intangible - I need to briefly give my account of it. The war on terror stands at the intersection of two of the greatest ideologies of our time: capitalism and the global military-industrial complex, on the one hand; and nationalism and the management of belonging, on the other. I refer to both ideologies as "Power" throughout this chapter.

Naturally, Muslims have a special relationship with the war on terror. On the one hand, obstructing the war industry's relentless march against evil is akin to standing outside of goodness itself. To stand and resist the war is to be made to feel as if you’re on the side of terror. On the other hand, not exalting the nation is to stand outside the boundaries of the "populace". To stand against the nation-state is to render all suspicions true - that you, in fact, do not belong. In both ideologies, to be seen (as in accepted) by Power has immense benefits - material and incorporeal.

Becoming the 'good' Muslim

I moved to Montreal after high school, leaving behind any discoveries I made of myself or Power, wandering further away from my mother’s wisdom. I remained inclined towards do-gooding nonetheless and saw myself as a "Muslim activist". But the desire to be seen features in even the most principled of intents.

I engaged fervently in both community activities, on the one hand - especially those relating to Muslim youth, which led me down a path of clinical psychology - and political activism that was both domestic and international, on the other. I separate Muslim and politics here because, of course, such are the terms of "good" Muslims. I remember distinctly the backlash I received as president of the Muslim Students' Association when I suggested we should be at the forefront of a movement on Palestinian rights - "the MSA is not political," I was told.

The attention given to me for becoming a Muslim male psychologist, by both Muslims and Power alike, was tremendous. Western psychology is a particular artefact of Power - a secular theology of sorts - and Muslim representation within it is highly coveted. My background and experience in working with the Muslim community, especially youth groups, suddenly saw incredible overlap with Power's desire to pacify the very distress it causes by "soothing from within".

Power always creates lucrative openings for everyone to enter its good grace as long as they play by its rules, and I was well on my way to becoming a psychologist who knows and plays his role. Representation is key in this process of pacification, and who better than a Muslim psychologist, who represents an ideal of secular sanctity (mental health professionals as secular priests of the soul) and diversity politics?

One is not allowed anger, of course, because the experience of anger, even if righteous, cannot exist outside Power's gaze. The refusal to condemn, then, is a refusal of existing wholly in the gaze of Power

In a few short years, like others blessed with both opportunity and privilege, I was suddenly being invited to consult on clinical and social issues pertaining to Western Muslims. Luckily, I had incredibly astute mentors who offered as much guidance and critical literature as I could digest (especially questioning psychology’s relationship to Power). And yet, even then with all this critical reflection, I still remained convinced of that age-old maxim of Power: "If you want to make a change, join us and change it from within."

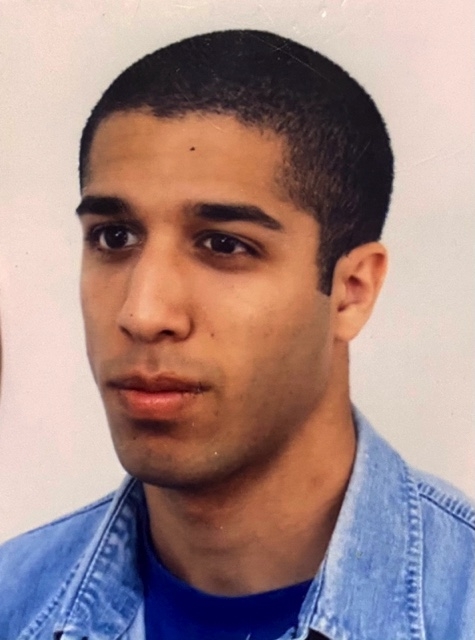

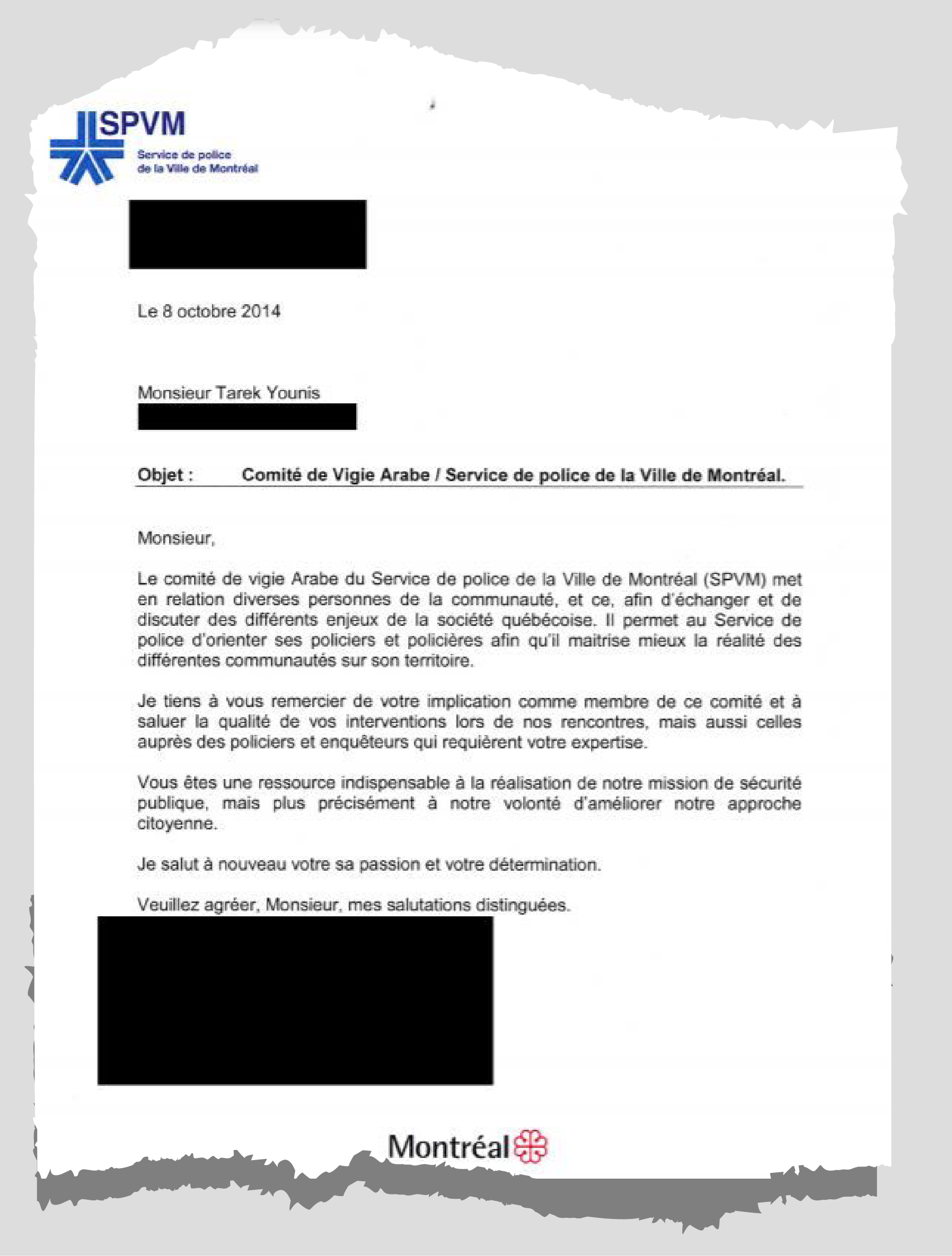

I soon began consulting for the Montreal police, as part of a special committee which discussed Muslim/Arab concerns. It was not uncommon to discuss issues regarding terrorism/radicalisation in these meetings. When they arose, the narrative remained static: yes, there are "bad Muslims" out there, but there are "good Muslims" (especially in the room) who were model citizens.

Our model-ness, our very presence, was the physical manifestation of condemnation. I held my misgivings at this thought, though I learned to assert (and failed at asserting) my apprehension at other times. Most of all, I learned that silence was an act with its own incalculable reward. This gift revealed itself at US–Canada border control.

The privilege of goodness

My cousin and I planned a road trip to New York. He was a football player who travels for training, including to Turkey. Naturally, we were held up as we crossed the northern border. As the hours passed, my cousin and I joked how the officer was checking his information under the "sports" page - surely "travels to Turkey for football" is flagged for suspicion.

But the officer then returned my cousin's documents and it turned out it was me all along. I was the cause of our wait.

I began questioning the cause of our delay as we entered the second hour. The agent didn't give an explanation. He said he still needed to check the system.

"Do you think someone who consults for the Montreal police would be a problem?" I asked, frustrated.

The agent looked up from his monitor. "Prove it."

Incidentally, I had just the evidence: a letter of recommendation on my phone from one of the assistant directors of the Montreal police. I showed it to the agent. He took the phone in his hand, stared it at it for a moment, and returned it.

"You should carry this with you every time you cross," he said. He handed back all our papers and we drove off.

My cousin and I laughed as we drove off into the Catskill Mountains. But I felt ashamed: this was not how my parents raised me. What of those who never had a letter? How do they fare, stripped of privilege?

Until today, I continuously receive offers to aid the war on terror, in some form or another. I'm a Muslim, male, clinical psychologist who specialises in the cultural and political dimensions of mental health; I have a long background of working with vulnerable youth within the Muslim community and social issues more broadly; I have a research background in Islamophobia and civic engagement. These are all highly desirable qualities for Power, especially given the number of Muslims who join counter-terrorism off their religious identity alone.

But know I would rather trash my PhD than partake in the war on terror.

Nous Sommes Quebecois!

In 2017, a shooter entered a Quebec City mosque and shot the rows of 53 people as they prayed the night prayer, killing six people and injuring a further 19.

Over 2,000 people filled the halls of the Montreal Olympic Stadium where the funeral prayer was held. I was asked to give a short speech alongside others. I initially wrote one for the Muslims in the audience. In the speech, I bore witness to the anger many felt towards the Quebecois political establishment which long legitimised the killer’s prejudices. Some of the politicians were there that day.

But I never gave that speech. I held back out of cowardice. Instead, I made the usual declaration of "overcoming adversity together" and in turn, as if mocked by my own spinelessness, the stadium shook with a chant: We are Quebecois! Nous sommes Quebecois!

What was it, in that terrible moment, which led us all to draw the gaze towards ourselves, to our nationalities, no less? To me, it is the sight of the dead which provoked an insupportable reaction: to look at them, to truly bear witness to the circumstances of their death, had inspired anger towards Power which had legitimised the killer's thoughts of Muslims. But this anger makes us seen in a bad light. Instead we implore Power's gaze towards us, demanding its good light even more.

'We are Quebecois! Can't you see us?'

Here the powerful and unsure "do not get angry!" shouted by Ralph Ellison's protagonist to onlookers of an elderly Black couple's eviction in Invisible Man resonated strongly with me. One is not allowed anger, of course, because the experience of anger, even if righteous, cannot exist outside Power's gaze. The refusal to condemn, then, is a refusal of existing wholly in the gaze of Power.

For a brief moment, the Quebec mosque attack made us aware of Power's gaze. But then we quickly forget the gaze and return to life within it as it defines the parameters of our experience. "Do not get angry!"

I wrongly believed our salvation is in our being seen, when our task is to see. When we feed someone in need, we should shun the cameras and the proclamation that "This is the true Islam!" - but feed more, nonetheless. As awful as that silence may be, as strenuous as our rejection of cameras will require, we must learn to find peace in rejecting Power's recognition.

One may claim to act in the unseen, or be seen only by God or for the sight of a particular group ("the oppressed"). But insofar as the gaze of Power encompasses all our actions, so too must its refusal be active.

Put differently, for every public act committed by Muslims in the sight of others, there must be an equal impulse to resist this act from being subsumed by capitalist or nationalist ideologies, which engulf all within the good Muslim/bad Muslim binary.

We must realise it is the performance of seeing, rather than the status of being seen, which binds us together. But for anyone reading this who, like me, is a coward, it will not be easy. For the greatest idol will always be the self's yearning to be seen.

Refuse to condemn, resist to be seen

My mother taught me we are far from the rational creatures we think we are, and that a loaf of bread will bring two people closer than all the world's philosophies combined. She taught that community is not an intellectual construct, but a performative one.

The refusal to condemn is not simply to refuse the "good Muslim" label - it is a resistance of our yearning to be seen by Power. To refuse to condemn, then, is to face the fear of mobilising on our own terms. There is no bravery without cowardice, no strength without vulnerability, no wisdom without ignorance. Insofar as the two drives of the world stand at their strongest - that is, capitalism and nationalism - our intentions will always waver between our desire to please God and Power.

Illustration by Mohamad Elaasar

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.