A year of resistance and repression in one Sudanese town

They saw it coming. Sudan's revolutionary project was unravelling, pulled apart by military forces intent on maintaining their power and protecting their position. A coup was on its way.

Mohammed*, a 37-year-old government employee and pro-democracy activist from Gedarif, eastern Sudan, was at home on the morning of 25 October 2021, when his internet and telephone connections were cut off.

He and his comrades snapped into action, following a carefully laid-out plan for the coup response and gathering in one of Gedarif's markets to begin a vast demonstration.

Two days later, Mohammed was arrested by military intelligence alongside a number of his fellow activists. Imprisoned at its headquarters, he was held there for over two weeks. From inside his cell, he could hear through loudspeakers the sound of cheering outside - a demonstration in support of the military had been arranged.

Initially, the interrogation was conducted in a "professional" manner. Then it turned brutal. "They brought a number of detainees in, beat them violently and insulted them," Mohammed told Middle East Eye. "Some were active in the resistance movement. Some were not."

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

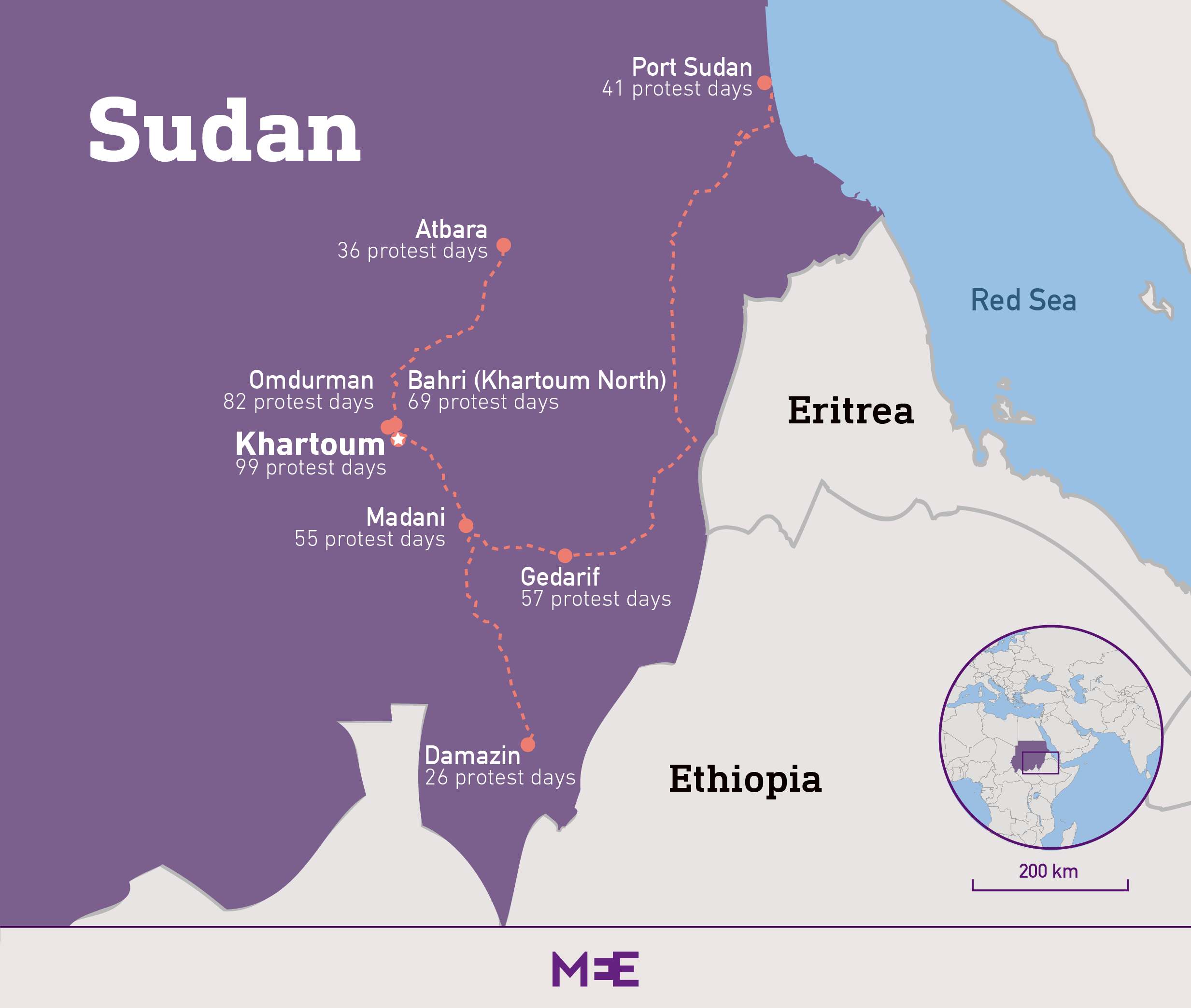

It has been a year since the coup that brought to an end the civilian-military government set up in the wake of the revolution that deposed long-time autocrat Omar al-Bashir in 2019. Since 30 October 2021, Sudanese have taken to the streets in protests over 105 days across 54 cities.

In response, the crackdown from an array of military and security forces has been brutal, with at least 82 protesters killed and 7,515 wounded.

In Gedarif, activists spoke to MEE about their year-long struggle to save Sudan's democratic movement. Alongside video and other documentary footage, their testimonies paint a picture of a year of resistance and repression in the eastern Sudanese town.

Beatings and intimidation

The list of allegations levelled at the military by revolutionaries - for which there is often accompanying evidence - is long and severe.

Across the whole of Sudan, the Sudanese Archive has verified videos of civilians being shot, beaten and hit with tear gas canisters by security forces.

With up to 14 armed groups operating in Sudan's capital Khartoum alone, establishing which forces have been at the forefront of the crackdown has not always been easy.

The army and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary, which grew out of the Janjaweed militias accused of committing war crimes in Darfur, are Sudan's two major military powers. But the handling of street protests has also fallen to the Central Reserve Police - created to suppress protests in the 1970s and recently sanctioned by the US treasury - the General Intelligence Services and local police, among others.

In Gedarif, pro-democracy activists told MEE that over the last year the RSF had conducted patrols with truck-mounted heavy machine guns known as "Dushkas", and that security forces had used rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs), stun grenades and tear gas. MEE has previously reported on the use of machetes by security forces to terrorise protesters.

The revolutionaries told MEE about being beaten and intimidated by the military, about having urine and faeces thrown on them, having their hair forcibly cut and about being hit with the base of rifles.

A Sudanese police spokesperson did not respond to MEE's requests for comment on the allegations. The Sudanese embassy in London also did not respond to a request for comment.

Border town

Sitting close to the border with Ethiopia, Gedarif is the capital of the state that bears its name. Known for its sesame seed cultivation, it is a lush, green place with a long history of agriculture. It is a multicultural city, attracting arrivals from different ethnic groups across the country and the African continent.

It is home to four refugee camps - with a fifth on the way - that mostly house Tigrayan refugees fleeing the war in neighbouring Ethiopia.

"Being a border town, Gedarif has always had a lot of trade going through it and was for the longest time a very rich place," Kholood Khair, director of Confluence Advisory, a think tank in Khartoum, told MEE.

"It saw its fortunes turn during the Bashir era because once Bashir saw how wealthy it was, he and his regime got their claws into it. So this, of course, led to massive degradation not just in agriculture but in other parts of the economy."

In power from 1989, Bashir and his Islamist administration patronised some of Gedarif's large farm owners, who responded by supporting him. But the flight of money and resources from the once-wealthy town and wider state prompted the formation of a strong and determined opposition to Bashir's rule.

Environmental issues like deforestation added to this sense of injustice, making Gedarif a focal point for the popular revolution that swept Bashir from power in 2019 after three decades.

"There was a sense that the regime could not maintain law and order in Gedarif," said Khair. "Some of the strongest resistance committees are there because of agriculture."

Resistance committees - informally structured groups of revolutionaries active in neighbourhoods across Sudan - have been at the heart of Sudan's pro-democracy mass movement since 2019.

Gedarif's resistance committees are organised according to sectors - north, south, east and west. On 31 October 2021, a couple of days after Mohammed was imprisoned, Adam, an 18-year-old from Gedarif's western sector resistance committee, was arrested for the first time by military intelligence alongside several other activists.

One of those was badly abused in front of Adam, his hand broken and his hair cut by intelligence personnel. This all happened, Adam said, inside the police station in front of several officers, including the captain, first lieutenant and lieutenant - "who did not intervene".

Weeks later they were released. Stepping back onto Gedarif's streets, Mohammed found anti-coup protests continuing to roil, with security forces unable to stop them. Military intelligence, meanwhile, hunted activists from the resistance committees.

"They were arresting activists, intimidating and beating them to try and neutralise the large protests. I was arrested for a second time on Sunday 24 April then released on Wednesday 27 April without any charge being brought against me," Mohammed said.

This time, security forces seized him at the ministry where he worked. "I was arrested by force by people who were not wearing uniforms and who were driving a car that did not have any official plates."

Arrests like these could take place at any place or any time. Activists described the spread of military power following the coup as frightening. The military presence in Gedarif's centre was overwhelming, yet still pro-democracy Sudanese evaded their grasp.

"The citizens of Gedarif are always able to get out and break this security cordon," said Zenab, a 24-year-old activist.

'A full military arsenal'

According to the Sudan Protest Monitor, the citizens of Gedarif have held organised protests on 57 days since the coup. Resistance committee members have always tried to plan routes that can avoid giving government forces an opportunity to loot and smash up the town's popular market.

Military trucks would look to enclose the activists and military intelligence forces became infamous, recognisable from their uniforms and the Toyota Land Cruisers they rode around in, adorned with special number plates.

"The forces wear civilian clothes. Their commander wears his official uniform. Another commander with the rank of major and a third, who is a first lieutenant, appear with him," Mohammed said.

They were not alone. Over the past year protesters have been assaulted by the army, the police and the notorious RSF paramilitary - "a full military arsenal" as 18-year-old activist Adam put it. "They all practise excessive repression."

Zenab has been on the receiving end of their brutal tactics multiple times. "They don't hesitate to hit you in the face," she said. "They also use sticks and the branches of trees, as well as tear gas."

On 28 March, she and fellow activists were confronted by police forces. "Police trucks were chasing the demonstrators and trying to run them over," she told MEE. "I went down a side street and there one of them shot me with a tear gas canister in the head. Another policeman hit me."

Pictures seen by MEE show Zenab in the aftermath of the attack, her brow, arm and denim jacket covered in blood, a Covid mask still on her face. Videos from the day show security forces using excessive violence against protesters as well as firing tear gas at them.

Gedarif is a town with an estimated population of just over 350,000. To many of its residents, it feels like a small place, with a tight knit community. Protesters often know the soldiers or policemen they face off personally - though on occasion, locals have reported seeing mercenaries from outside the state. And uniforms and equipment make each branch of the security forces easily identifiable.

The RSF has been a key part of the crackdown in Gedarif, as elsewhere in Sudan. Headed by Mohamed Hamdan Daglo, commonly known as Hemeti, the paramilitary was born from the Janjaweed militias deployed by Bashir's government to quash uprisings in Darfur.

The Janjaweed - "devils on horseback" - stand accused of genocide and widespread atrocities in Darfur. The RSF is also held largely responsible for the Khartoum massacre of 3 June 2019, during which at least 120 civilians were killed.

Now the second-most powerful man in Sudan after its de facto leader General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, Hemeti and his brothers have their own significant sources of influence and wealth, controlling gold mines in Darfur and enjoying the patronage of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

"Many situations are stuck in my memory," Zenab said, when asked about the violence faced by protesters over the past year.

She spoke of intelligence officers harassing demonstrators in a "very close and personal way, abusing them, threatening them and arresting them".

Threatened with death

A video verified by MEE shows a notorious colonel in Gedarif trying to arrest a teacher at a protest. The colonel is stopped by the crowd. "He is the one who interrogated us in prison," Mohammed said. "It was a political interrogation - there was an agenda behind it, he wanted to undermine the revolution and its meaning."

In another case, the colonel is accused of supervising the arrest of 16 high school students at a demonstration. The students were detained at the police station and then handed over to the government agency responsible for children and families.

Adam, the 18-year old activist, told MEE that when security forces interrogated him, they were particularly annoyed by the media pressure resistance committees had been able to keep up: the names and details of intelligence personnel had been published and the arrests of activists were regularly denounced throughout the year.

'I was taken out of the cell and threatened with death. They continued beating me in the evening until the captain came and I was released.'

- Osman, activist

On 19 April, Osman, a 24-year-old activist, was arrested, having been under surveillance for weeks. He knew something was up. His brother had been threatened and Osman left his home and moved to a nearby neighbourhood to escape the heat. But he was spotted on the street by chance and pursued by a military officer on a motorbike.

He was asked about the financing of the resistance committees. "I didn't answer the questions, so they took me back to the cell, where one of them tried to drop the faeces and urine of another prisoner on me," Osman said.

"I was taken out of the cell and threatened with death. They continued beating me in the evening until the captain came and I was released."

The captain accused Osman of getting paid to write about the revolution and of orchestrating media campaigns for the revolutionaries. After he was released, Osman went to the hospital for treatment following the severe beatings he'd received.

Looking back over a year of this resistance and repression in Gedarif, Mohammed's account of his own deprived and dislocated childhood stands out.

Mohammed's family came to Gedarif from the Nuba Mountains, from where they were displaced, losing their livestock and livelihood.

Growing up there, his father's salary was "insufficient", he said, the health insurance system didn't work and he and his siblings had little to no educational opportunities.

His older brother had to leave school in order for Mohammed to continue his education. The family was targeted by Bashir's government. The water did not work properly and the roads were crumbling. But Mohammed left school and got a government job, all the while organising to bring that government down.

In Gedarif, the border city in the east, there was and is a rich tradition of this resistance.

Osman, a "revolutionary and believer in change", sees his city as a "mini Sudan, where all the components of Sudan are gathered, where there is diversity and social interdependence". It is here that he and his fellow activists will keep fighting.

This story was reported in partnership with the Sudanese Archive and Sudan Protest Monitor.

*Names have been changed for security reasons

Illustration by Hossam Sarhan

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.