ANALYSIS: US declares cyberwar on IS, but what will it attack?

It was a bold and provocative statement: Ashton Carter, the US defence chief, told a Senate committee that the US was going to war with the Islamic State group on a new front - cyberspace.

"The objectives there are to interrupt ISIL command and control, interrupt its ability to move money around, interrupt its ability to tyrannise and control population, interrupt its ability to recruit externally," Carter told the Senate armed services committee on Thursday, referring to the Islamic State group.

"We're bombing them, and we're going to take out their internet as well."

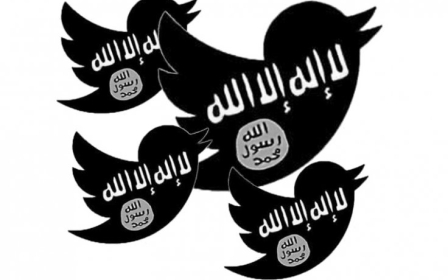

The Islamic State group (IS) is infamous in its use of social media for propaganda and recruitment, releasing videos of its victories on the battlefield, its abhorrent treatment of captives and sending its message to supporters and enemies alike through magazines such as Dabiq.

Up until now, the public purpose of US cyber warfare has been dominated by objectives of defence and deterrence. The comments by Carter have brought US offensive operations, led by a new 5,000-strong force, out of the shadows.

But experts have raised questions about what the US's "Cybercom" organisation can do; "taking out" the internet, in the words of Carter, is relatively easy, but doing so would affect nearby allies and civilians.

Nor do all IS communications come from within the areas it controls in Syria and Iraq. The decentralised nature of the internet allows users to mask locations, hide identities, and circumvent direct attacks. Close one account, attack one domain, and they pop up again elsewhere; a game of whack-a-mole ensues.

Nevertheless, Peter Singer, a cyber warfare expert for the Washington-based New America Foundation, said that Ashton's announcement was the first step in the "normalisation" of waging cyberwar.

"The operations against IS in the cyber domain are notable. They are the first time the US has openly declared that it is engaging in military attacks in cyberspace," he told Middle East Eye.

"The US has been active in the past, but in covert espionage operations, ala Stuxnet. So its a big step in the 'normalisation' of cyber operations, not just to do it, but to openly admit to doing it."

The US is believed to have been involved in the deployment of the "Stuxnet" virus to disrupt the Iranian nuclear programme.

Indeed, reports in the New York Times last year suggested that Cybercom had prepared "project Nitro Zeus" to attack Iran if negotiations to rein back its nuclear ambitions failed.

The project was said to be capable of disabling Iran's air defence, communications networks and parts of its power grid through hidden code placed inside Iranian networks.

However, Singer said the methods being used against IS were on a lower level.

"There's no IS integrated air defence to target via cyber means, or physical damage to cause by targeting IS-owned SCADA systems," he said, in reference to coded military signal operations.

"What we are focused more on is their communications both internally but also externally with social media to the public and to its new cells in other nations such as Libya.

"Think of this as the opening, but not the final view of where this is all headed," he said, adding that the techniques were in their infancy.

How they manifest themselves, therefore, remain to be seen.

IS already has a tight grip on internet access in the areas it controls. It limits civilians to internet cafes, closely monitors all traffic and uses sophisticated satellite internet systems rather than traditional "wired" connections for high-level communications.

As reported by Reuters, recent Iraqi attempts to stop the group using such "V-sat" systems, which can be bought for $2,000, have largely been unsuccessful.

"What's still difficult for us is controlling V-sat receivers which connect directly to satellites providing internet services that cover Iraq," an Iraqi communications ministry official told the news agency, adding that the firms running the services did not monitor "end users".

The US has already reportedly disabled the internet wholesale in Syria in 2012, although this was apparently unintentional.

Edward Snowden, who blew the whistle on his former employer, America's National Security Agency, said its hackers accidentally shut down the country’s access for three days while attempting to access a service provider.

The internet blackout was widely blamed on the Syrian government, although it blamed “terrorists”.

Singer said that Carter's claim of "taking out their internet" was not literal; networks used by IS in Syria and Iraq are vital for civilians and groups other than IS.

"It will be far more nuanced," he said. "They will not be taking away all internet from all of Syria and Iraq. Indeed, some of our allies in local rebel groups use the same civilian networks."

Indeed, and internet "take-down" would appear to breach the US's own cyber strategy, which states the US will always conduct cyber operations "under a doctrine of restraint ... to ensure the internet remains open, secure and prosperous".

Singer's comments were echoed by Dan Clifford, a cyber security expert who consults for hostile-environment security companies.

"Most of the infrastructure that keeps internet and phone access in place is relatively fragile," he told MEE, but added that such attacks would have wider effects on local communities.

"It's more of a socio-economic issue when this access is shut down, and that's the incentive for not doing it.

"For anyone in the region who is attempting to live and work, shutting down access to the outside world, suppliers, colleagues or loved ones only exacerbates their problems.

IS can also find ways around the attacks - such as "V-sat" systems.

"Any group with funding will move on to more expensive communication solutions and it will be the everyday person that is left unconnected."

The US, it would seem, has allies in unusual places. The hacker group Anonymous has repeatedly said it is waging cyberwar on IS - disrupting its Twitter accounts, hacking IS sympathiser's websites and stealing its bitcoin transactions.

The Independent reported that Anonymous leaked information about IS members after the group killed 130 people in the November Paris attacks, and claimed to have shut down 5,500 Twitter accounts.

After the Brussels attacks in March, it reasserted its campaign.

"We severely punish Daesh on the 'dark net', hacking its electronic portfolio and stealing money from the terrorists," said an Anonymous member in a message on Youtube, referring to IS by an Arabic acronym.

But these efforts will not defeat a group that, despite its high-profile online presence, is fundamentally focused on controlling territory and people in the "real world".

The US cyberwar, therefore, is part of a "full-spectrum" response: gathering information, tracking militants and disrupting communications to complement traditional military action.

As the chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff General Joe Dunford told the Senate committee: "The overall effect we're trying to achieve is virtual isolation. And this complements very much our physical actions on the ground."

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.