Israel-Lebanon maritime deal: Domestic pressures deflate gas deal optimism

Optimism over the weekend that Israel and Lebanon were inching closer to agreeing to a US-brokered draft deal demarcating a maritime border over disputed gas fields in the Mediterranean has waned after domestic criticism within both countries.

It was also reported that Lebanon's government would not agree to hold an official signing ceremony for any deal and if there was an agreement it would be delivered to a UN representative in the presence of US envoy Amos Hochstein in a room without an Israeli representative, and after the Israeli side signed it, the agreement would immediately enter into force.

Meanwhile, former Israeli premier Benjamin Netanyahu, who is locked in a closely fought general election campaign to be held in less than a month, accused the current Prime Minister Yair Lapid of signing over the country’s natural resources to Lebanon and Hezbollah.

In a series of tweets on Monday aimed at framing Lapid as weak on national security, Netanyahu's Likud party wrote that the prime minister was “handing a huge Israeli gas reserve to Hezbollah, something Netanyahu never agreed to”.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

'Below our rights'

Contours of what a final deal may look like have already emerged.

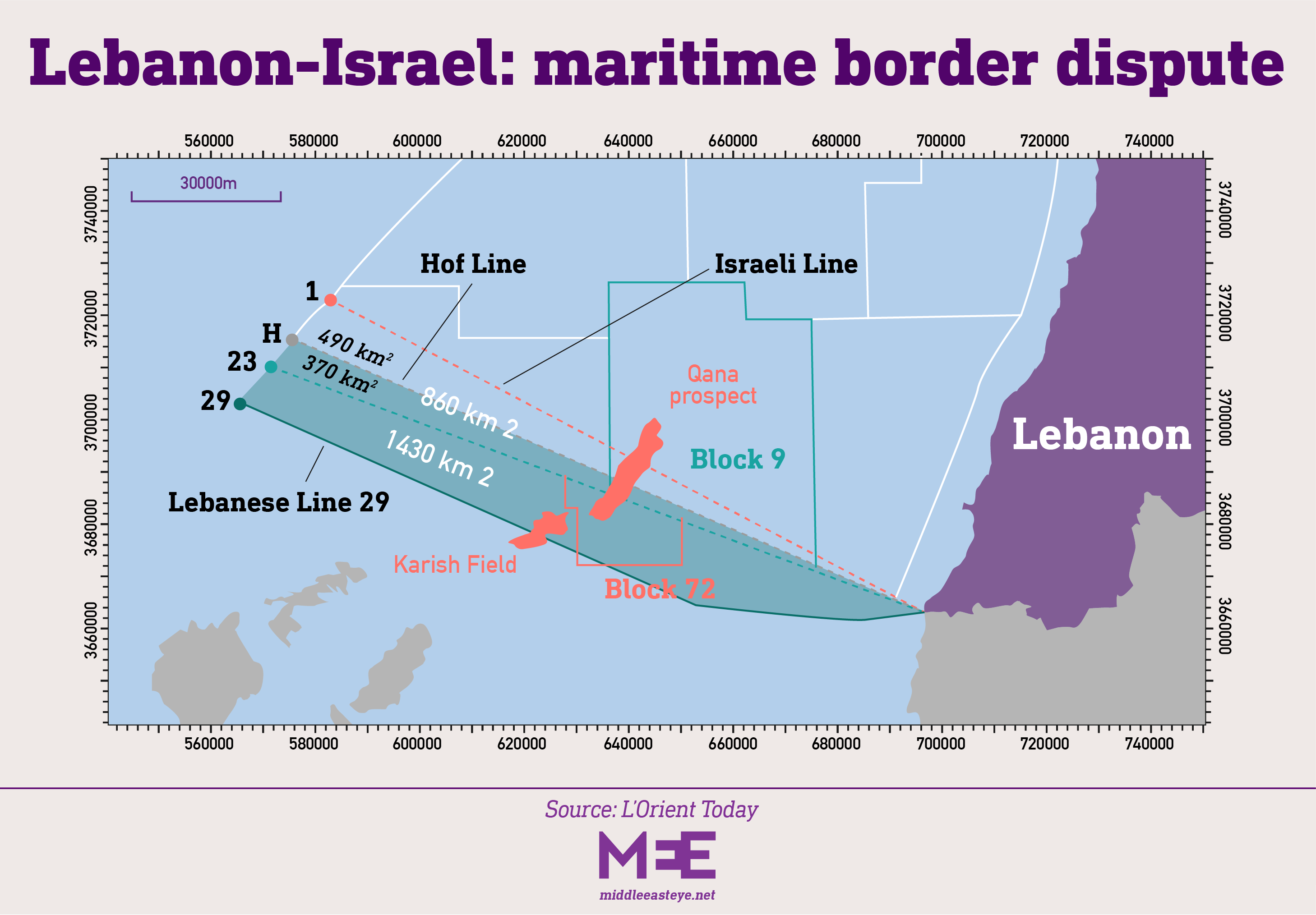

The US proposal will be based on Line 23, which is located north of the maximal version that the Lebanese put forward some years ago.

The Karish gas field is located southwest of the line, meaning that it will remain under complete Israeli control. The northeastern field, Qana, will go to the Lebanese, with Israel giving up its claim.

In return, Israel is working on a formula with the French energy firm Total to get a slice of any future revenue that the prospective Qana field generates. What that final number for a slice of the revenues looks like may make or break the deal on both sides of the border.

"There will be no shared revenues for Qana between Lebanon and Israel, but something agreed upon and being discussed between Israel and Total separately, out of the company's profits," said Marc Ayoub, an energy expert at the Issam Fares Institute at the American University of Beirut.

That's the rumour that's going around anyway, said Ayoub, given that a final deal hasn't been published. And that formula is likely to be an important red-line for Lebanon which wants to avoid the perception of normalisation with Israel.

"Therefore, there is no production-sharing agreement between the Israelis and Lebanese in the future," added Ayoub.

For Lebanese politicians, sealing the deal while preserving their red lines has been a more difficult balancing act, given that the country's economic and political state has meant a potentially weakened hand on the negotiating table.

"Lebanese politicians have been pushing for that deal to escape the repercussions of the economic crisis and to try and get some money based on potential gas prospects," said Ayoub.

"For experts and the majority of the public, whatever Lebanon will sign is already below our rights because Lebanon's right according to maritime laws is Line 29," he added, referring to the Karish field, which Israel has refused to discuss as part of the negotiations. Lebanon's economic freefall has constrained politicians' ability to push these claims.

'Completely irresponsible'

If signed, however, a maritime deal could prove a milestone in the relationship between Israel and Lebanon according to some experts. Particularly in helping reduce tensions and allowing both sides, in particular cash-strapped Lebanon, to capitalise on potential gas discoveries.

The current draft deal, only 10 pages long, has been in the making for years but had ground to a halt in 2020 over Lebanese demands over a previously undisputed part of Israel's waters. But it's Netanyahu's toxic rhetoric that could scuttle the deal on the Israeli side.

"Netanyahu, in his completely irresponsible way, talked about abrogating the agreement after the elections if he wins," said Professor Yossi Mekelberg, who teaches international relations at Roehampton University and is an associate fellow of the MENA programme at Chatham House.

"If anyone needs another reason, which I personally don't need, to not vote for him, here it is," added Mekelberg in remarks to MEE.

Appearing to drop its former fervent opposition to any deal, Hezbollah described recent developments around the US proposal as "a very important step".

On Saturday, Parliamentary Speaker Nabih Berri, a powerful Hezbollah ally, also deemed it "positive" in a marked change of tone for the group which scuttled the agreement in 2020.

'People of the past'

Mekelberg believes that people on both sides need to move on and ignore agitators like Netanyahu and Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Hezbollah who have often sought to push "their narrow interests and not the interest of their countries".

Lapid has taken a risk in pushing this deal during a tight election race. In addition, Israel's Defence Minister Benny Gantz has urged Netanyahu to refrain from comments that "endanger the deal". But so far, to little avail.

"There is nothing that merits not signing the agreement or changing it or doing a Trumpesque JCPOA [move]," said Mekelberg, referring to Donald Trump's abandonment of an international nuclear agreement with Iran in 2018.

Any attempt by a Netanyahu administration to scuttle the deal if he makes it back to power would have significant consequences, warned Mekelberg.

"The guarantor of this agreement is the United States which means a direct confrontation with not only Lebanon but with the United States, and for what?" he said.

There are other geopolitical considerations too. With Lebanon in economic ruin, the prospect of a deal could potentially help the country become a natural gas exporter and improve the country's economy.

Israel may not want to see a strong Lebanon, but nor does it want to see the country teetering on the brink of total collapse, which could create a lawless environment, potential refugee flows, and the undermining of further international investment in the Eastern Mediterranean basin.

What's at stake?

In Israel, much of the discussion over the maritime deal has been framed as the country giving up territory.

Elai Rettig, who teaches energy policy and national security at Israel's Bar Ilan Univerity, said such views primarily emanate from a lack of understanding in Israel and Lebanon over the difference between economic and territorial waters.

"For many, it's 'territory', and no side wants to give territory to the other," Rettig told MEE.

Whereas territorial waters confer sovereignty over the waters adjacent to a state, an exclusive economic zone (EEZ), which is what is being discussed between Israel and Lebanon, gives a sovereign right to the coastal state's rights below the surface of the sea.

At stake between the two sides are 860 square kilometres of water and overlapping claims over the Qana gas field, of which about a third crosses into what Israel considers its EEZ.

"[People] also don't see the bigger picture, that the more gas exploration occurs in the area, the more everyone wins, so everyone needs to play nice and reach compromises," said Rettig.

"For many, it's either 'our gas' or 'their gas', and it's a zero-sum game."

'Win-win' deal

Rettig says more needs to be done to explain the deal to the public and admitted that there was a risk for the Lapid government in "particular that anything that relates to territory or sovereignty leads to high emotions in Israeli public discourse".

"Land is very important, and it sits at the heart of the Israel-Arab conflict," he said.

It is also important to note that the Qana gas field discussion is so far speculative. No one knows how much, if any, gas is recoverable from the area. However, its proximity to the Karish gas field in Israel's claimed EEZ, which is expected to come online in 2023, has raised hopes that Qana could offer similar results.

'Although the Lebanese say it's nothing and they are not talking to Israel... you can't ignore the reality there is kind of an agreement between two countries'

- Orna Mizrahi, INSS security think tank in Israel

Israeli gas exports are already connected to a series of pipelines with Jordan and particularly Egypt and may, in the future, also include Lebanon. Israeli gas, while not in itself a game changer, would help the EU manage its looming energy crisis following the Russian-Ukrainian war.

"The countries will have to find some kind of configuration to combine their resources and export their gas together," said Rettig.

"Each country alone does not justify the construction of an entirely new infrastructure [pipeline to Europe or a new LNG plant], but together there's more potential."

Orna Mizrahi, a senior researcher at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) in Israel following a long career in the country's security establishment, calls the deal a "win-win" for a region that has become so accustomed to zero-sum dealings.

The royalties that could be shared from the Qana gas field would establish an economic umbilical cord with Israel and - whisper it - even deepen political ties with Lebanon.

"If there is no deal, nobody will get anything," Mizrahi told MEE.

"Now, if we have a deal, it assures that our security concerns are met. If Hezbollah hurts the Israeli side, it would also end up hurting the Lebanese side."

Some in Israel see the gas deal as a prospectively locking Hezbollah into an economic agreement which would also reduce its room for manoeuvre on the political front.

For its part, Hezbollah's softened stance towards an agreement reflects new realities that the group faces: a shattered economy; crumbling public and private institutions; and the effects of fighting for 10 years in Syria which have left a mark on the group.

"Although the Lebanese say it's nothing, and they are not talking to Israel, you can't ignore the reality there is kind of an agreement between two countries who have had hostile relations since their establishment," said Mizrahi.

"I think it's a great change. Some people may disagree, but it's a window of opportunity, and maybe we can take it to another level.

"So from a strategic perspective, it shouldn't be underestimated."

'Constructive precedent'

With the Israeli political kaleidoscope in flux, Mizrahi is dismayed that the maritime deal has become political, calling it an "awful" development which ignores "the real interests of Israel".

Despite Netanyahu's political bluster - seen by many as a desperate attempt to claw himself back into the prime minister's chair - neither Mekelberg or Rettig believe he would renege on a deal if victorious.

"That would be a precedent for Israel because each government tends to respect international deals signed by the previous government," said Rettig.

On a more hopeful note, Mairav Zonszein, a senior analyst on Israel-Palestine at the International Crisis Group, says a deal between Israel and Lebanon could bring some rationality back among different actors in the region.

"A deal based on negotiation and compromise sets a constructive precedent that issues can be settled through diplomacy and not through violence," she told MEE.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.