UN earthquake rescue system blocked in Syria and Iran by US sanctions

A life-saving coordination system used by the United Nations’ emergency response network was blocked in Syria after February’s devastating earthquake because of US sanctions, Middle East Eye can reveal.

MEE has discovered that the online system also appears to be inaccessible in Iran, where the rapid coordinated deployment of search and rescue teams might be the difference between life and death for people trapped under rubble after an earthquake.

The 6 February earthquake killed tens of thousands of people across hundreds of kilometres of southern Turkey and northern Syria, but thousands of people were also saved from collapsed buildings by search and rescue teams.

Iran, which sits on a highly active seismic faultline between the Arabian and Eurasian plates, is frequently shaken by earthquakes.

Tehran and its surrounding urban areas, with a densely housed population of about 15 million people, is considered to be one of the world’s megacities most vulnerable to a catastr0phic earthquake.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Internet freedom and digital rights campaigners told MEE the issue appeared to be a consequence of “overcompliance” with US sanctions targeting Syria and Iran by the American technology company which provides the mapping software on which the UN system is built.

Amir Rashidi, an Iranian internet security and digital rights researcher, told MEE: “The problem with the sanctions which we’ve been dealing with for a long time is overcompliance by the technology companies. There is a fear in these companies that they might face charges or fines.”

The system has been developed by the UN’s International Search and Rescue Advisory Group (Insarag), a global network of urban search and rescue teams that typically deploy to disaster zones within hours of a disaster.

Insarag is part of Ocha, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, which “coordinates the global emergency response to save lives and protect people in humanitarian crises”.

'Superpower' rescue system

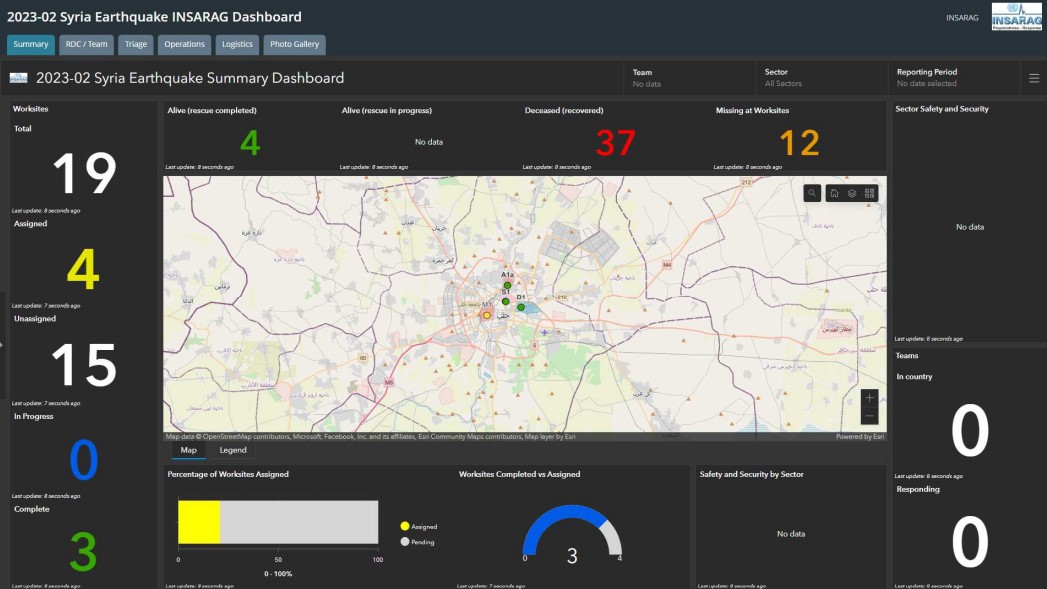

The Insarag Coordination & Management System (ICMS) was first used during the response to the 2020 Beirut port explosion and has been hailed as a “superpower” for those in charge of coordinating rescue efforts.

One of the developers of the ICMS has described its importance as “delivering key intelligence to the right people at the right place at the right time”.

Utilising a cloud-based mapping platform, or geographic information system (GIS), called ArcGIS, it provides a real-time overview that enables emergency response coordinators to better understand the situation on the ground.

Urban search and rescue teams teams can log details of rescue efforts via mobile phone apps, such as people saved, bodies recovered, requests for equipment or reinforcements, worksites completed, as well as send photos and other information.

'There are ways to ensure your tech is accessible. It’s just whether it is a priority'

- Mahsa Alimardani, human rights researcher at Article 19

The ICMS is still a work in progress, however.

An ICMS dashboard for the emergency response in Turkey - the biggest operation in Insarag’s history, involving about 150 search and rescue teams - was set up within two hours of the 6 February earthquake.

In an Insarag review of the response, the system was acknowledged to have been a “useful tool”, though some search teams reported connectivity issues and stressed the priority of rescue work over data capture and “filling in forms”.

In Syria, however, where Insarag's response was far more limited, the system was inaccessible on the ground in the critical first days after the earthquake.

Just seven urban search and rescue teams - from Tunisia, Armenia, Algeria, China, Russia, Lebanon and the United Arab Emirates - were deployed to government-controlled areas of Aleppo and Latakia.

But an ICMS dashboard for Syria was only set up on the second day of operations. Teams on the ground then reported that they could not access the system.

A message posted on an online noticeboard for urban search and rescue teams arriving in Syria on 8 February said: “There is an issue with ICMS in Syria. The server of arcgis.com is blocked. It is not possible to connect to the server.”

Middle East Eye has learnt that instead of logging data into the ICMS directly, teams were asked to fill in paper forms and then send images of the forms via WhatsApp for others to input the information.

Urban search and rescue teams were later advised to download a VPN app to use the ICMS.

Peter Wolff, head of Insarag’s information management working group, told MEE that the small scale of the operation in Syria meant that use of the ICMS was not essential.

“It was only a few teams and they can coordinate themselves. It was good that we tried it and we worked out how it works without connectivity. It was, for us, a huge learning effect,” said Wolff.

Prohibited countries

MEE understands that issues with access to the ICMS in Syria were raised by Insarag with the software company that runs the ArcGIS platform.

ArcGIS is developed and maintained by a California-based company, the Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI).

ESRI does not allow its products to be used in countries subject to US sanctions, and lists both Syria and Iran as prohibited countries on its website.

MEE asked journalists in Iran and Syria to try to access the ICMS login page. They were diverted to webpages with error messages that read “Error loading site. Status: 500" and “403 Forbidden”.

“These are not something being generated by the Iranian government or any other government,” said Rashidi.

“These kind of error messages are usually generated by those who develop these tools or websites. Probably they are blocking access to that service.”

ESRI has not responded to repeated queries and requests for comment from MEE.

Issues with accessing ArcGIS in Iran previously came to light in 2020, when a Johns Hopkins University Covid-tracking tool built on the platform was also blocked, at the height of the pandemic.

Humanitarian exemptions

Digital rights advocates have long campaigned for governments imposing sanctions to allow exemptions for communications technologies with a humanitarian purpose, or those that promote freedom of speech in countries where internet access is subject to government censorship.

Last year, the US government announced a general licence “to increase support for internet freedom” in Iran, in response to a harsh crackdown on protesters, enabling technology companies to provide cloud-based services in the country, including web maps and internet communications.

A US Treasury Spokesperson told MEE that it had also issued a general licence to support "immediate disaster relief efforts in Syria". General licences are "self-executing", the spokesperson said, meaning that companies do not need to apply to the Treasury to take advantage of them.

But this licence wasn't issued until 9 February, three days after the earthquake, when search and rescue teams were already at work on the ground in Syria.

Campaigners say many technology companies have also been slow to update their policies to allow their products to be used in countries affected by sanctions.

'There was absolutely no transparency [in Iran] during Covid… With an earthquake it is the same. So access to this kind of information is essential to public safety'

- Amir Rashidi, digital rights researcher

“There are ways to ensure your tech is accessible. It’s just whether it is a priority,” said Mahsa Alimardani, a researcher for human rights organisation Article 19, who focuses on freedom of expression and access to information online in Iran.

“I guess the learnings from the Covid-19 map haven’t been applied,” she told MEE.

Alimardani said that Insarag and Ocha should also be “paying attention to issues of accessibility”.

Wolff told MEE that Insarag had run training sessions with an Iranian team, in which they had collected data using their mobile phones, but he said these sessions had taken place in Turkey.

Insarag had also conducted an earthquake exercise involving participants based in Tehran, he added.

“So at least sometimes it works,” Wolff said, in response to a question about whether Insarag was aware of ICMS accessibility issues in Iran.

He said Insarag had also updated its training material to advise ICMS users on connecting via VPN, or submitting photos of paper forms to people with access to the system, in situations when the system was inaccessible on the ground.

'Disaster of the century'

Insarag officials say that the lack of access to the ICMS did not make much difference to the search and rescue effort in Syria.

Wolff said urban search and rescue teams had arrived late to the country, when hopes of finding further survivors were already fading.

At an Insarag meeting in Singapore weeks after the earthquake, team leaders identified other issues in Syria, including the government’s lack of awareness of international response mechanisms and the lack of a basic structure to receive and coordinate assistance, including search and rescue teams.

MEE has previously reported on the failures of the UN rescue effort in opposition-controlled northwest Syria.

But in Iran, the breakdown of Insarag's coordination system could have disastrous consequences for search and rescue operations.

In February, Tehran City Council chairman Mehdi Chamran warned that an earthquake in the Iranian capital would be “the disaster of the century”.

Insarag deployed teams to Iran following a 2003 earthquake with an epicentre close to the southeastern city of Bam. More than 41,000 people were killed and 87 percent of buildings in the city destroyed, according to a UN assessment.

Iran is currently seeking Insarag membership. Iranian and UN officials held an online meeting earlier this month to discuss the idea of two Tehran-based urban search and rescue teams joining the network, according to a report in the Tehran Times.

MEE asked Ocha whether the issue of sanctions and the ICMS had been discussed in the meeting, but had not received a response by the time of publication.

Rashidi told MEE that data gathered through the ICMS could be vital in the aftermath of an earthquake in Iran, because of local restrictions on internet use and strict controls on the flow of information.

“There was absolutely no transparency during Covid. No one knew what was going on. With an earthquake it is the same. So access to this kind of information is essential to public safety,” he said.

“Access to the internet is a right, and censorship and sanctions are both violating Iranians' right to internet access.”

Geospatial intelligence

Other ESRI customers appear to have been more successful in using the company’s mapping systems to monitor events in Syria.

ESRI also provides cloud computing services to the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), which delivers geospatial intelligence, or Geoint, to other intelligence agencies and to the US armed forces.

The role of the NGA and the importance of Geoint in monitoring the movements of competing factions in Syria during the country’s ongoing civil war were highlighted by Robert Cardillo, the agency’s director, in a statement to the House Armed Services Committee in 2017.

Cardillo told the committee that the NGA was continuously monitoring “a web of competing interests, conflicting parties, and complex alliances” in Syria and Iraq.

“This includes monitoring Syria and Isis’s response to actions by traditional state actors, such as Russia, Iran and Turkey, as well as non-state actors, such as Hezbollah, Shiite militias and Kurdish militias.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.