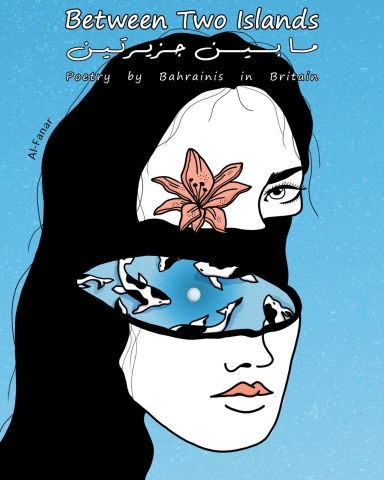

Between Two Islands: How British Bahrainis found a home in poetry

These Seas, the first poem of the poetry anthology Between Two Islands, opens with the image of a pearl diver - an iconic symbol of Bahraini culture:

A reincarnated pearl diver

diving headfirst into ancestral seas

finding pearls that resemble faces

each dive is one summer holidayStay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis,

starting with Turkey Unpacked

for a necklace that proves I am from here

This image which poet Taher Adel uses to thrust readers into this world is so deeply associated with this land that it is even referenced in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

But where Gilgamesh dove in search of youth, and pearl divers of the recent past dove for their livelihood, the poets in this collection of poetry by British Bahrainis are trying to grasp something perhaps more elusive - their sense of identity.

Between Two Islands emerged from a desire to bring Bahrainis in Britain together to learn and write poetry. A desire that arose from feelings of isolation, brought on both by the pandemic and by the arts sphere in the UK, where I personally - as a poet and editor of the anthology - often feel underrepresented.

I had spent many years crafting my art in the privacy of a notebook and, more recently, in the multicultural spoken word scene in Manchester.

I wanted a space where I could feel free to be myself, as a Bahraini Arab navigating two countries and two languages, without needing to justify any aspect of my existence

But I wanted a space where I could feel free to be myself, as a Bahraini Arab navigating two countries and two languages, without needing to justify any aspect of my existence.

The project, funded by Arts Council England, began as a series of six weekly online workshops which ran during January and February 2021, with 13 participants aged between 15 and 50, many of whom had little or no previous experience in creative writing.

A student at the University of Strathclyde, Maryam al-Saleh had not written creatively for a few years prior to the workshop, which she used as an opportunity to edit and hone some of her older drafts.

“It was a much-needed experience, and helped immensely alleviate the loneliness that this pandemic had brought on us,” al-Saleh says. “I enjoyed our discussions of poems, but I enjoyed even more the discussions we’d have on other topics that we can all relate to as Bahrainis in the UK.

“I vividly remember our talk about beaches, how different they are in the UK and Bahrain, and how we all agreed beaches in Bahrain felt more welcoming and ‘homier’ - if that’s a word!”

With the support of mentors from spoken word collective, Young Identity, and writing development organisation Commonword, who are both at the heart of Manchester’s poetry scene, along with the Arab British Centre and the Liverpool Arab Arts Festival, we were able to launch the workshops to great effect.

Within weeks of advertising the project in December 2020 on social media, the workshops were set up and attendees signed up, and by the new year, we were all set to go.

I led the workshops with Amina Atiq, a Yemeni-Liverpudlian poet, whose art celebrates the working-class Yemeni diaspora in Liverpool, and who was able to inform our work with her own community’s experience. Atiq’s works include the play Broken Biscuits and most recently, Scouse Pilgrimage and Backbencher with Tara Theatre.

“Poetry was the beginning of generating crucial conversations around the idea of home and identity,” says Atiq. “All the participants proved to show courage and commitment in all the workshops and I feel honoured to have watched all of them grow into performance poets.”

While a few participants were poets, we also had among us doctors, engineers, teachers, students and various professions in between. In those dark winter months, trapped indoors as the pandemic raged around us, poetry was our respite.

Indeed, one poem in the anthology speaks directly to that experience. Fatema Abuidrees, a psychological well-being practitioner in Brighton, like so many participants, had not written poetry since childhood.

She takes the term “legacy hand” - meaning a hand raised during a Zoom meeting and never put back down - to question what of our “legacy” remains.

Written in the poetic form of a ghazal (traditionally a form of love poem, with a repeated refrain at the end of every couplet), we are left thinking about what lingers in this digital age, when our separation from home is heightened:

In our gated age of Zoom IDs and passwords, a legacy hand lingers

Raised to speak to dismembered heads, enduringly it waits, strained, it lingers

I am my language

The workshops were split into two segments: reading and writing. In order to remain inclusive, we selected poems that were available in English translation, and made both versions available to all. This meant everyone could read and analyse each poem in either or both languages, reproducing their inner thoughts in the one that best suited them.

Even if a person could not engage with the Arabic, they were exposed to it in an unpressured environment, and our group was supportive and non-judgemental. We were each able to explore poetry and the Arabic language on our own terms.

But there was a fine balance to maintain working between our two dominant languages in the workshops.

Some of our participants could only speak either English or Arabic, while others were bilingual but more comfortable speaking one language over another.

Each of us had our own unique relationship to Arabic, and by extension, our identity (as one oft-quoted verse of Mahmoud Darwish goes, “I am my language”).

Each poet experimented with language in their own way, but one that I will remember is in the poem La’ib by translator Fatima Alhalwachi. The poem is written in alternating English and Arabic lines. Here, the English word “lane” and Arabic word qadamayn (feet) rhyme:

Here I am again

unravelling memory lane

بين الليمونة والتوت

حافية القدمين

Switching languages in poetry, especially between left-to-right English and right-to-left Arabic, often has the effect of visually emphasising the gulf between the two, and the conflicting ideas they symbolise (these symbols vary of course from one poet to another).

But Fatima’s bilingual rhyme unifies the two languages. While the poem can be enjoyed by monolingual readers of both languages, its bilingual reading elevates it and unites the two languages to create something which is greater than its parts.

If migrants and diasporans become hybrids of both “home” and “host” cultures, then this is expressed eloquently in these lines.

Communicating with Baharna ancestors

Regardless of their more dominant spoken language, everyone who appears in Between Two Islands happened to hail from a marginalised Arab community, the Baharna (or Bahrani) Arabs, including myself.

The Baharna Arab identity exists parallel to the Khaleeji (Gulf) Arab identity, with its own history of working-class struggles and liberation movements that is largely eclipsed and little discussed outside of Baharna circles.

One of the oldest Arab communities in Eastern Arabia, the Baharna - who mostly live in Bahrain and Saudi Arabia - have suffered frequent discrimination over the years. In Bahrain, the village Baharna was subject to a system of forced labour (sukrah) and arbitrary taxation (raqabiyya) in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

A hundred years later, the United Nations would criticise the “systemic harassment” of Shia populations in Bahrain, the majority of whom are Baharna. Nearly all major political opposition leaders, imprisoned since 2011 and still behind bars, are from this community.

Whether one engages with these political issues or not, the daily lives of Baharna are affected. A viral video in 2020 spoke to the experience of the Millennial and Gen Z Bahrani who struggles with Arabic, due in parts to classist disregard of their dialect as “backwards”, and workplace discrimination against people with Bahrani family names and accents.

While not all the workshop participants were political, as Baharna, everyone’s identity was politicised.

While not all the workshop participants were political, as Baharna, everyone’s identity was politicised

All these things taken together make being Bahrani something people find difficult to discuss and be proud of. But the demographics in the workshops meant that we could celebrate this important part of our identity without having to worry how to justify this identity - not to a western gaze, nor a Khaleeji gaze either - and could instead immerse ourselves in it.

We read Bahrani folk songs, listened to the dialect, and discussed our relationship to our culture.

As part of the workshops, I sent a care package to everyone which included Arabic coffee and a traditional, hand-crafted container made from palm tree fibres (a guffa). Picking up the guffa, we asked participants to write down: what would their parents have kept in this container? What will they store in it? What do they imagine their descendants will store in it? In doing so, we entered dialogues with past and future generations.

Just as Adel’s poem spoke of ancestral seas, the poet (who chose to remain anonymous) of the following poem, Buying A Ticket, communicates with their Bahrani ancestors and roots themselves in the land:

My soul, my veins spreading

Across the land

through every Bahrani woman, child and man.

In creating the workshops, I hoped that everyone would feel safe to explore their marginality, to centre it and draw power from it.

R Probert is another Bahraini who chose the anonymity of a pseudonym. He was a teenager during the "Arab Spring" and had his own close encounters with violence. He marched in protests with family, saw the excessive use of birdshot pellets which tore through his home, and felt the sting of tear gas first hand.

Probert draws from his activism, and his poem is inspired by a database he had maintained tracking the cases of political prisoners. When he showed me the draft, I suggested that he take it straight to the source and write the poem in Microsoft Excel:

May you never click to

Make neat green ticks

Confirm

Allegations of abuse.

Torture? (tick)

Though several poems addressed political issues (such as Zahra Shehabi’s Two Islands), Probert’s was by far the most candid, capturing the dehumanisation many Bahraini prisoners have suffered.

The poet has drawn from their own experiences in the human rights field, and the prisoners in their poem find themselves imprisoned a second time, in an Excel spreadsheet, leading me to wonder whether human rights reports that record abuses are themselves dehumanising in their own way.

Sense of dislocation

There is a sense of dislocation throughout the poems in the anthology. The sea features strongly in our shared imagination. The sea is the source of our wealth and our food; it is also where the oil fields lie. Living in the UK, we cannot help but compare the two seas - and Britain’s waters always come short.

In the poetic theory text What the Date Palm Said to the Sea (1994), Dr Alawi Al-Hashimi writes: “If the date palm, for Bahrani people, is the real mother without whom they cannot live, then the sea is rightfully their father, giver of sustenance and life, though the sea is also a cruel and grim father.”

While this quote did not inform Between Two Islands, it is a reflection of the power of our shared heritage that this understanding of the sea and land is reflected in the anthology.

In many of our poems, the sea is both inviting – as in Adel’s These Seas - and an ambiguous danger - as in Buying a Ticket.

In Jenan Alhasabi’s poem, An Island With the Sea as the Escape, the sea gradually transforms from a childhood sanctuary to a dangerous route off the island:

We race to the beach, the gentle waves cool our feet

as the raging orange sun sears the loose black cloth on my head

By the end of the poem, the island pictured has the feeling of an open-air prison: the smells of tarmac, fumes and humidity strangle the senses.

Nowhere is this sentiment - of trees as community - better seen than in Zainab Meftah’s conversation with a raisin. The raisin explains that it was raised in another country in the company of her sister grapes and passed from farmer to factory to trader and eventually into the poet’s hand - far from the tree she was born in.

Though I did not know it at the time, and though most of us had little engagement with Bahrain’s poetic tradition, we were expressing concepts about the sea - and also of trees - which come naturally to the Bahraini disposition. Sanctuary and peace is found in trees, which appear often in the poems and, to my mind, represent community.

The raisin’s journey becomes a meditative metaphor on the migrant’s journey. Meftah’s metaphor captured the dilemma most of us in the workshops wrestle with.

O Exile, Where Shall I Begin?

If each poet has dived to retrieve pearls of identity, Zahra Shehabi’s poem, Two Islands, suggests a murky harvest, a dissatisfaction with both British and Bahraini society:

Can I affiliate myself with an ice cold island that doesn’t accept me,

… Can I sit in a فريج of people who disregard the oppression in their society?

Yet her use of dialect with the word fareeg (which is displayed in Arabic text in the poem and means “neighbourhood”) also represents a close yearning to be in the heart of Bahrain’s villages. Shehabi, who resisted the idea that she might be a poet, has gone on to write poems for the NHS trust she works in, connecting to her community in the UK through poetry.

We need a diaspora community that can better represent second-generation Bahrainis, who do not always fit comfortably in the first-generation environments our parents established, nor in a British society that rarely reflects them

Shehabi is drifting “by a hybrid identity” - in her poem is the longing of a people who feel at odds between the language in their souls and the language on their tongues.

That is a common diaspora and migrant experience, and when I take our work together as a collective whole, I sense an underlying need for a diaspora community that can better represent second-generation Bahrainis, who do not always fit comfortably in the first-generation environments our parents established, nor in a British society that rarely reflects them.

“My relationship with Bahrain had dwindled, so when this opportunity came up, I decided - reluctantly - to join, and what a great decision it was,” says Shehabi.

“Not only did the workshop provide a great platform to connect with people torn between two cultures and identities, but I was able to learn and appreciate the skill of poetry - an escapism from the overwhelming hospital environment in which I work.”

My boat approaches

There was a shared sense of anxiety among the participants that we would one day lose something important to us. The ghostly choir of ancestors in Mohamed Arab’s My Boat Approaches the Field of the Past tell him, in metered verse, that they exist within him, and will never disappear - perhaps defining the core value we are striving for.

In my own poem, my persona is joined by countless stragglers in a journey along a moonbeam, finding solidarity amongst the alienated. On the other hand, H Alshehab’s Oh Exile, Where Shall I Begin? finds peace among family amidst the alienation of the West.

These poems echo one another because they were written in response to the same urgent questions we were all asking. The structures of society and community we diaspora Bahrainis have, in both Britain and Bahrain, are not providing us with everything we need. So what is it that we need?

I think the answer lies within the anthology itself. I was 19 when the Arab uprisings erupted in Bahrain in February 2011. That year, when so many friends, protesters, children, doctors, journalists and hundreds of others were arrested and tortured, some to death, left a traumatic impact on Bahrain’s psyche.

That single year has defined my generation, and it feels as though I have relived it across the last decade. The cousin imprisoned for life, the family forced to close their business, the friend rendered stateless. Often, I seem to exist as a reaction to these events, responding to waves of a storm my boat can hardly withstand.

Yet through poetry, we were able to reset our relationship to our homelands and to ourselves, able to reconsider and move forward. Between Two Islands is without a doubt an anthology deeply nostalgic of a certain vision of diaspora Bahrainis, of a Bahrain of villages, palm trees and sea, but I think it uses that to express a vision for the future.

I see it as an incomplete work, because it demands to be built upon. Most importantly, however, Between Two Islands has created new links for our community, ones which are built on our generation’s own terms. That is an empowering feeling, and that was at the heart of what we set out to do.

Between Two Islands, edited by Ali Al-Jamri, is published by No Disclaimers and available online.

The Future: A Between Two Islands Soundscape will be published digitally at the Liverpool Arab Arts Festival on 1 October; there will be a live event with the poets on 30 October.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.