Akbar the Great: How the Mughal emperor set an example for religious tolerance in India

In a famous anecdote, the Mughal Emperor Akbar holds court with representatives of the major religions, who each take turns to make the case for their faith being the correct one.

With their arguments exhausted, the Indian ruler took time to consider what he has heard and make his judgement. But his announcement shocked those present.

“The God of everyone is the same,” he said, repeating the chant of a fakir outside the palace gates instead of the men of religion present within the palace.

While the story is likely exaggerated, it summarises the popular modern recollection of a ruler whose realm stretched from Afghanistan to the Deccan Plateau of the Indian subcontinent.

While many Hindu nationalists will disagree, memories of Akbar's rule recall a period of relative intercommunal calm in India, and for some Indians a model of religious pluralism and tolerance.

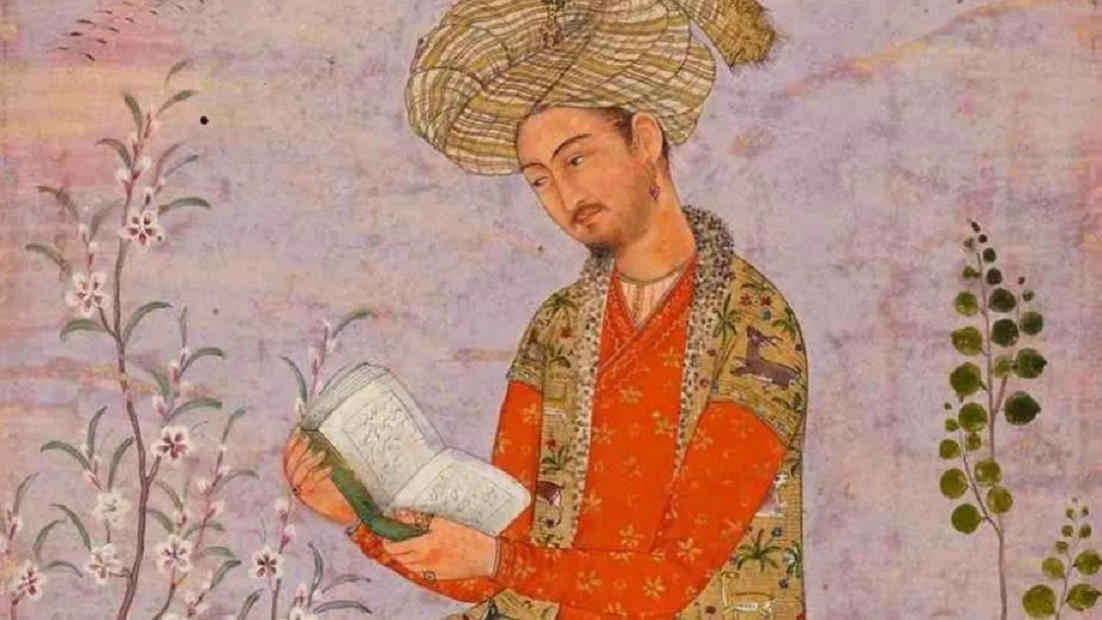

Formally named Abul Fath Jalal-ud-din Akbar, Akbar the Great was the third emperor of the Mughal Empire.

Born in 1542 in Umerkot, in what is now Pakistan’s Sindh province, he is remembered for his rejection of religious intolerance and the measures he took to ensure the security of non-Muslims under his reign.

Ascending to the throne

Akbar was the grandson of the founder of the Mughal Empire, Babur, a Timurid prince who conquered large swathes of the Indian subcontinent in the early 16th century.

The Mughals were descendants of the famed Turco-Mongol conqueror, Timur, who claimed to be a descendant of the famous Mongol leader Genghis Khan.

But despite his royal pedigree, there was no guarantee that Akbar would go on to lead the fledgling empire during his early years.

His father, Emperor Humayun, was beset by rebellions and ultimately forced out of power by Afghan tribesmen.

He was only able to reclaim his throne with help from the Safavid Persians while the Afghans were preoccupied fighting amongst themselves.

When Akbar was 14, Humayun died and the young man ascended to the throne. He was trained to rule by Bairam Khan, a military commander and regent at the Mughal court.

Khan continued to advise Akbar until the young ruler came of age and was able to establish his own leadership.

Unlike his father, Akbar established a reputation for his inclusive leadership style and he was able to stabilise the Mughal Empire, and even expand its borders.

Under his military leadership, the Mughals captured fertile regions, such as Bengal, and secured access to the Arabian Sea through their conquest of the regions of Sindh and Gujarat.

These newly acquired territories contained religiously-diverse populations that were often majority Hindu, even when their former rulers had been Muslim.

As a result, the success of Akbar’s rule depended on how well he could manage relations with his non-Muslim subjects.

Relations with Hindu subjects

With a mixture of political pragmatism and a genuine interest in Hindu tradition, Akbar sought to protect freedom of religion for all those in the areas he ruled.

For example, after subduing the Rajput tribes in Northern and Central India, he respected their religious needs by guaranteeing their right to public prayer and granting them permission to construct and repair temples.

Many within his court questioned Akbar's decision to allow Hindus to worship freely.

Even his own son, Salim, is reported to have asked why Akbar allowed Hindu ministers to spend state money building a temple.

Akbar is said to have responded by saying: "My son, I love my own religion... [but] the Hindu (minister) also loves his religion. If he wants to spend money on his religion, what right do I have to prevent him... Does he not have the right to love the thing that is his very own?"

The Mughal emperor also attended Hindu religious festivals and had Hindu literature translated into Persian for use by his courtiers.

Interestingly, Akbar’s relationship with his Hindu minister, Birbal, has had a long-lasting influence in India, and collections of anecdotal exchanges between the two are still popular in the country.

These accounts probably incorporate earlier fables and are today used as children’s stories with an accompanying moral or lesson.

Akbar was also an avid fan of Hindu devotional performances by Mirabai, the wife of Prince Boka Raj of Chittar.

Akbar is said to have shown his appreciation by laying a diamond necklace at the base of her statue of the Hindu deity Krishna.

The Mughal emperor also married several Hindu princesses, such as Jodha Bai, Bikaner, and Jaisalmer, who were allowed to keep their faith.

In addition, a Christian wife named Mary was also given a personal chapel in one of his palaces.

Religious syncretism

Described as an illiterate bibliophile and possibly dyslexic, Akbar liked to have books read out to him in court, particularly on topics like philosophy and religion.

According to statements made in a court biography written by his son, Salim, Akbar "was always with the learned of every religion and creed" and "was always talking with the learned and the wise".

Such was his intellectual curiosity that foreign visitors reported being amazed at his huge personal library, which contained more than 24,000 volumes in Sanskrit, Persian, Greek, Latin, Arabic, and several south Asian languages.

A proponent of interfaith dialogue, Akbar conducted religious discussions at his court in Fatehpur Sikri with theologians, poets, scholars, and philosophers of the Christian, Hindu, Jain, and Zoroastrian faiths.

The Mughal ruler was also a follower of the Chishti order, a Sufi school of thought known for emphasising love, acceptance, and tolerance.

He was well-versed in Sufi practices and is remembered for instituting "Suleh-e-Kul," a policy of peace that was designed to encourage tolerance and harmony between people of all backgrounds.

His belief in religious tolerance is further demonstrated in a letter Akbar sent to King Philip II of Spain, where he claims to have interacted with "educated men of all religions" rather than relying solely on Muslim experts for his education.

This interest in religion and policy of tolerance culminated in Akbar’s founding of Din-e-Ilahi (literally meaning, "God's religion").

This concept brought together different beliefs and schools of thought and was inspired by the idea of "Wahdat al Wujud" (Unity of Existence), a philosophy first developed by the Sufi mystic Ibn al-Arabi and later adopted by other Sufis.

This idea asserts that all creation is an illusion and that God alone is the source of true reality.

By establishing the Din-e-Ilahi, Akbar encouraged the notion that all religions are interconnected and they all lead back to one ultimate truth, which is God.

It was less a traditional faith than an umbrella religion that sought to find the commonalities in different faiths.

India today

Akbar’s legacy, both real and imagined, has provided a vision of an India where Muslims, Hindus, and other minorities can enjoy religious freedom.

While warfare and conquest were certainly a part of Akbar’s reign, once subdued, conquered peoples of different faiths and cultures were encouraged to coexist in relative peace and harmony.

However, Akbar’s legacy is now being erased by Hindu nationalists.

For example, India’s ruling BJP party has been accused of erasing Mughal history from school textbooks, including references to Akbar.

Underlying this is the belief amongst Hindu nationalists that Muslims are not native to the subcontinent and so deserve to be excluded from Indian history.

Mughal rule, alongside that of other Muslim empires in India, is being recast in terms of foreign invaders conquering and subjugating native Hindus.

According to Indian historians, such readings of history ignore the fact that Hindus and other religious minorities were often part of the ruling class within these dynasties and that the rulers themselves were thoroughly assimilated into Indian culture.

In light of this revisionism, Akbar’s message of religious tolerance and mutual respect between communities remains acutely relevant.

Akbar did more than bring unity to his fragmented country. Under his rule, the Mughal empire tripled in size and became the wealthiest and most powerful Muslim empire of the early modern period.

The ruler left a solid framework for his successors to build on, and he continues to serve as a timely reminder of the need for pluralism.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.