Dog fighting, drug deals and tattoos: The hidden lives of Iran’s criminal underworld

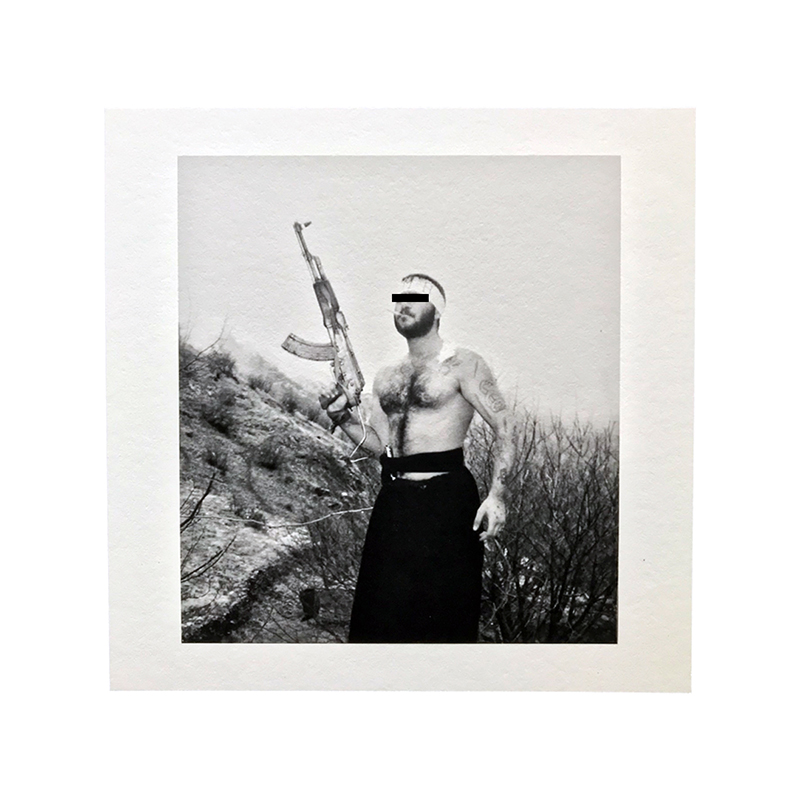

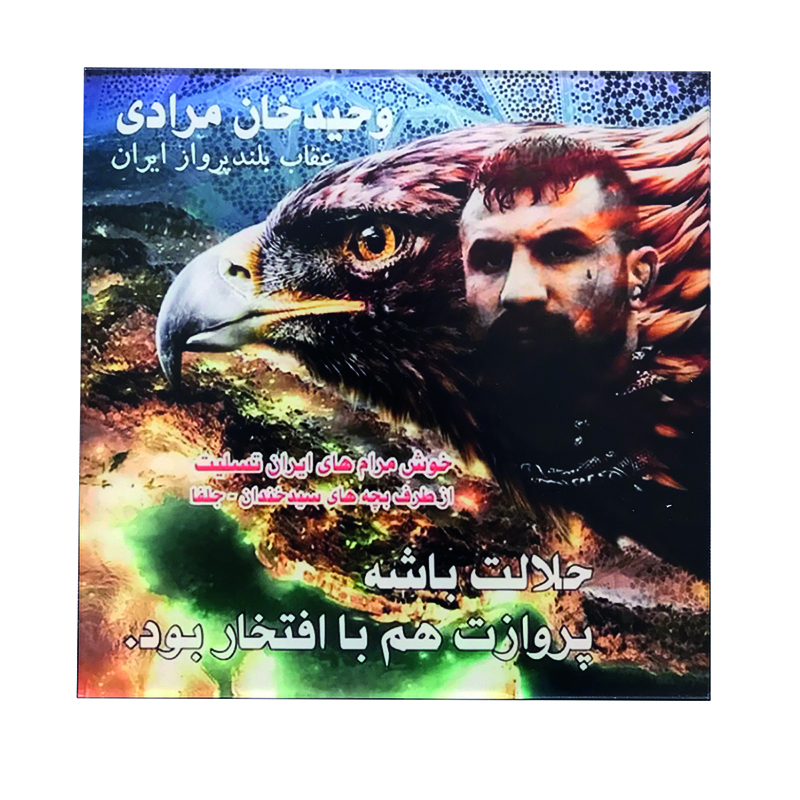

Nicknamed "The Eagle of Iran" by his peers because of the golden eagle tattoo on his back, Vahid Moradi was a notorious gangster who spent most of his life in and out of Iranian prisons.

Not much is known about his upbringing or childhood, but throughout his life, The Eagle served multiple prison sentences for various crimes, including gang-related fights and being a member of a criminal organisation.

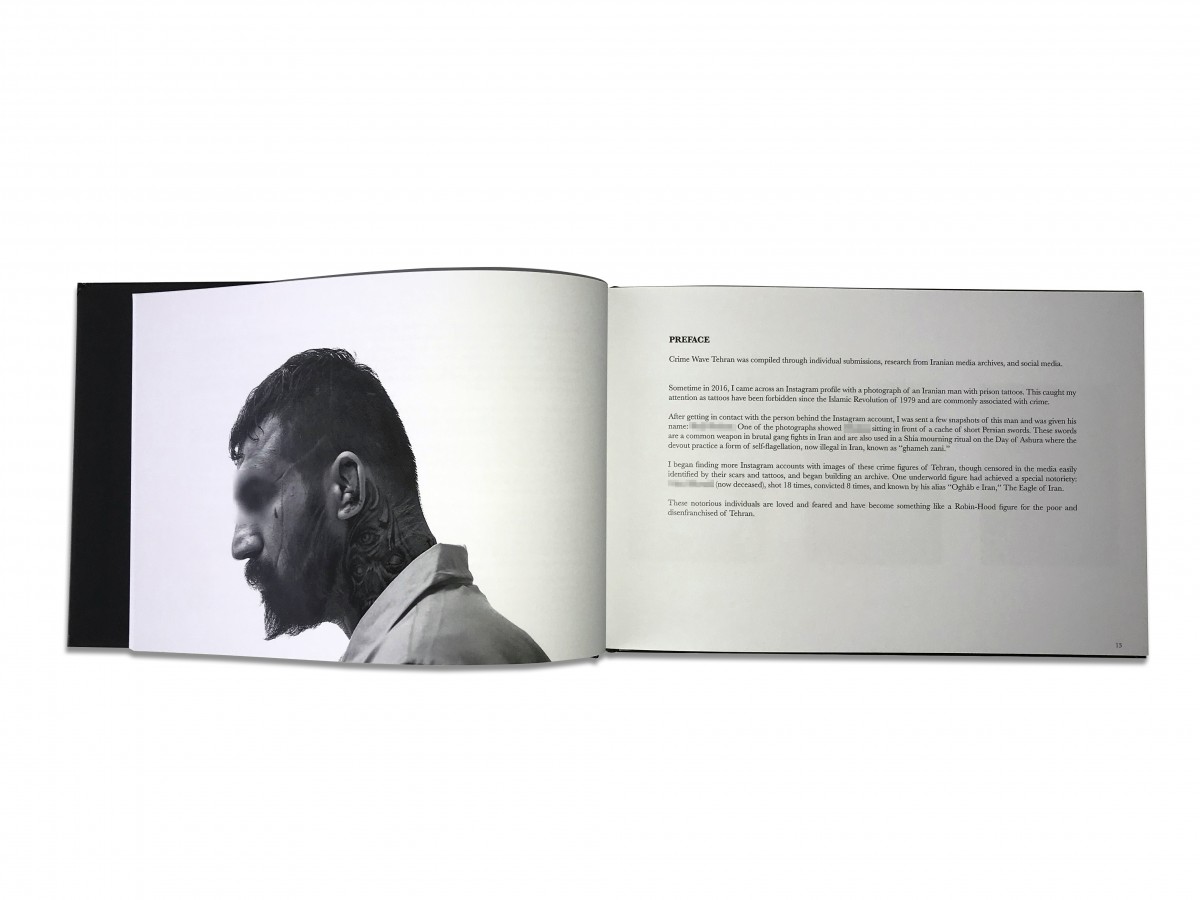

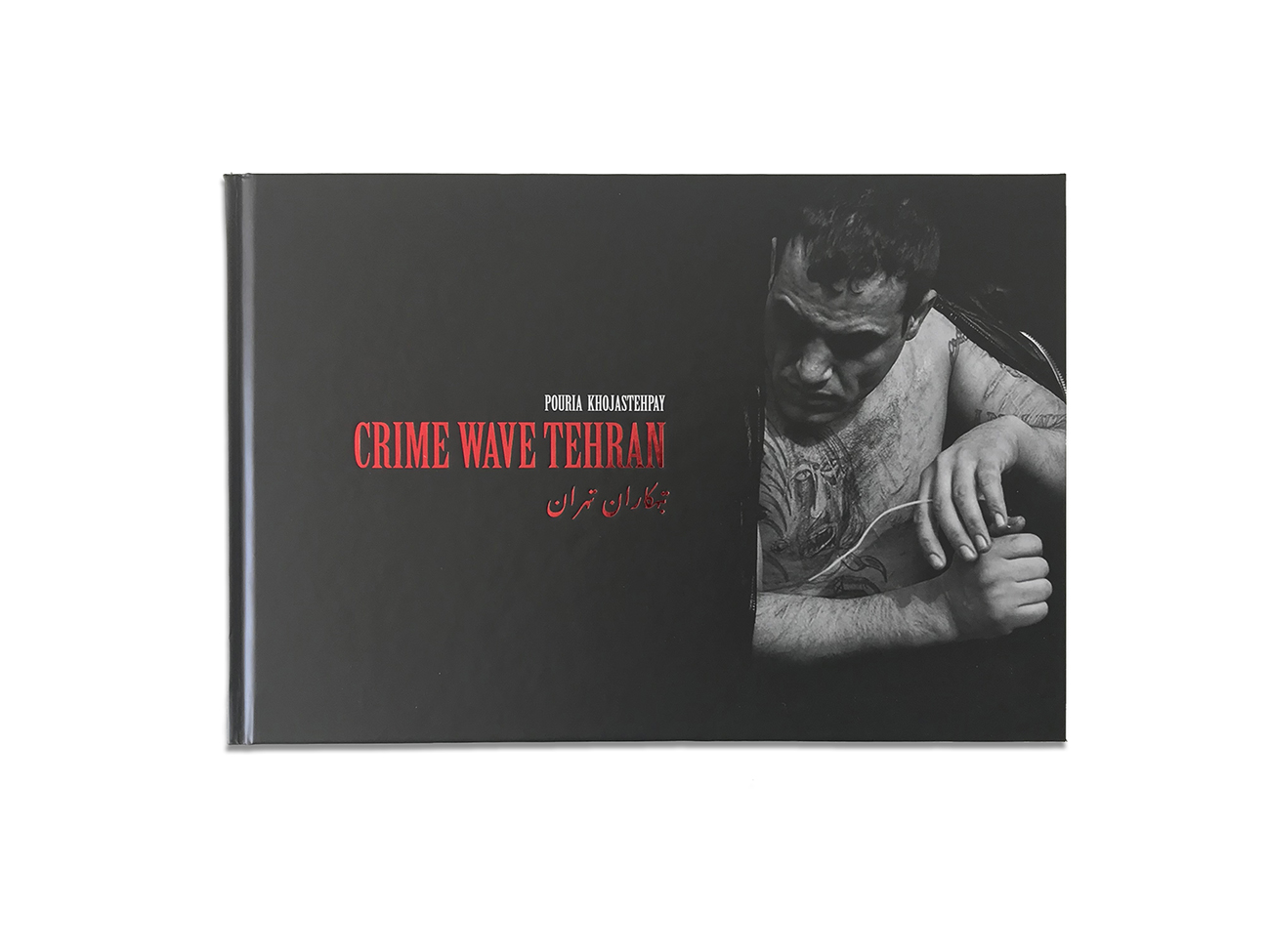

Moradi is also one of the men profiled in Crime Wave Tehran, a research project and photo book on Iran’s criminal underworld, edited and published by Iranian-Dutch artist and researcher Pouria Khojastehpay in 2018.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Khojastehpay describes “The Eagle” as “a real and respected gangster in every sense”. “He was the main inspiration for the book and my print series,” Khojastehpay told MEE.

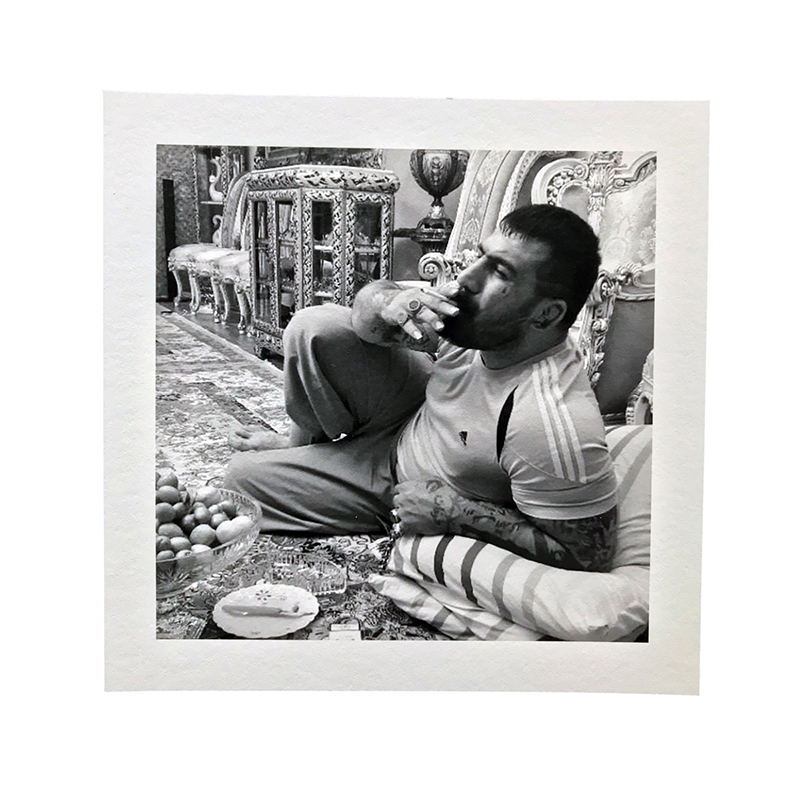

In one photograph, Moradi stands with a hand placed respectfully over his heart. He would blend seamlessly into the surrounding crowd were it not for the tattoo of a gun on his hand and the other of a tear drop below his left eye.

Known for being somewhat of a “survivor”, he managed to endure several bullet wounds, before his luck eventually ran out.

In 2018 The Eagle was arrested for the murder of an associate during a party thrown to celebrate his prison release. Soon after, back in jail, he was killed by fellow inmates following a dispute in the prison yard.

In the book, a portrait of Moradi taken on the day he was arrested shows him standing alone. He is dressed in a collared shirt and his eyes have been blurred out by Khojastehpay. Moradi’s chest and neck tattoos are visible, including a scorpion inked into his left ear and the teardrop which sits under his left eye, above a large scar that runs across the side of his face.

According to the book, in an interview with Iranian media outlet Rokna News, conducted on the day of his arrest, Moradi had said: “Imprisoning me will not change anything. I am who I am.”

The Eagle left behind a wife, and a son, who Moradi had dreamed might become a doctor or an engineer one day, according to Khojastehpay’s sources. Both still live in Iran.

Since the book's release, Khojastehpay has gone on to produce an entire exhibition on the subject. Although currently on hold due to Covid-19 restrictions, a planned Paris show will feature some of the images from the book as well as additional images, all of which will be presented as a print series titled Gangstehran.

“The book was a general coverage and introduction to the concept and world. The prints are more of a sociology project of how they [gangsters] portray themselves. They show their strong body language,” Khojastehpay told MEE.

The world of organised crime

The Eagle’s story is just one of several powerful portraits Khojastehpay has gathered over four years in an aim to upturn perceptions of this overlooked segment of society.

Authored and published through Khojastehpay’s own publishing company 550bc, Crime Wave Tehran is a carefully curated and meticulously edited collection of over 90 photographs documenting the portraits and lives of some of the country’s most notorious gang members.

Taken between 2013 and 2018, the images in the book give the reader a glimpse into the criminal underworld in Iran, and also the private lives and personalities of these men, some of whom have spent much of their lives in and out of incarceration in Iran’s toughest prisons, including Rajai-Shahr and Ghezel Hesar in the Tehran suburb of Karaj.

'Many Iranians had no idea this existed in Iran'

- Pouria Khojastehpay, Dutch-Iranian artist

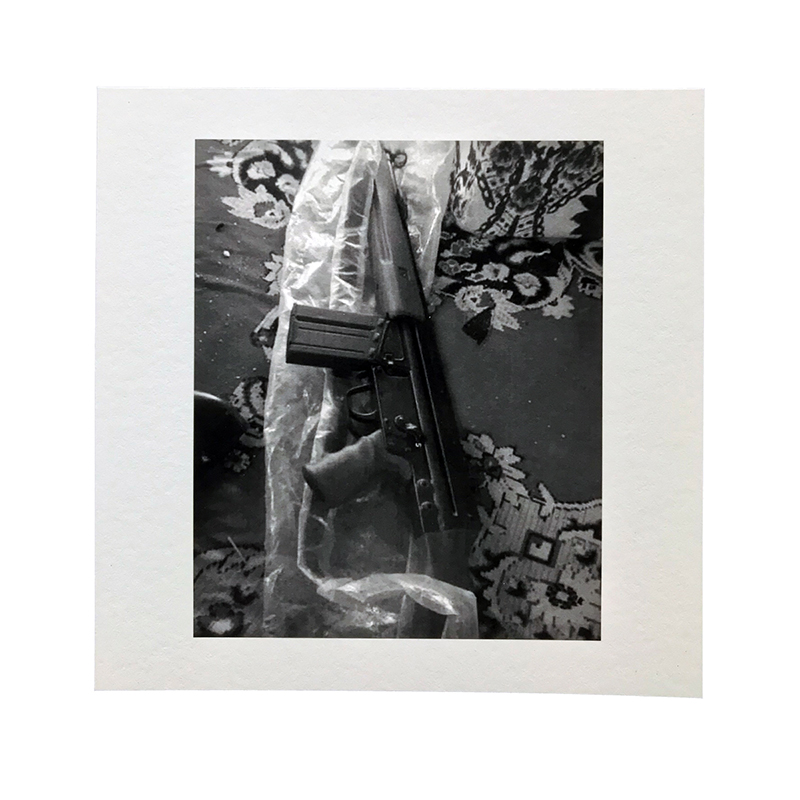

Through the book, we are made privy to intimate scenes from bank robberies, drug trafficking, and dog fighting, but it also touches on this section of society’s interactions with the state.

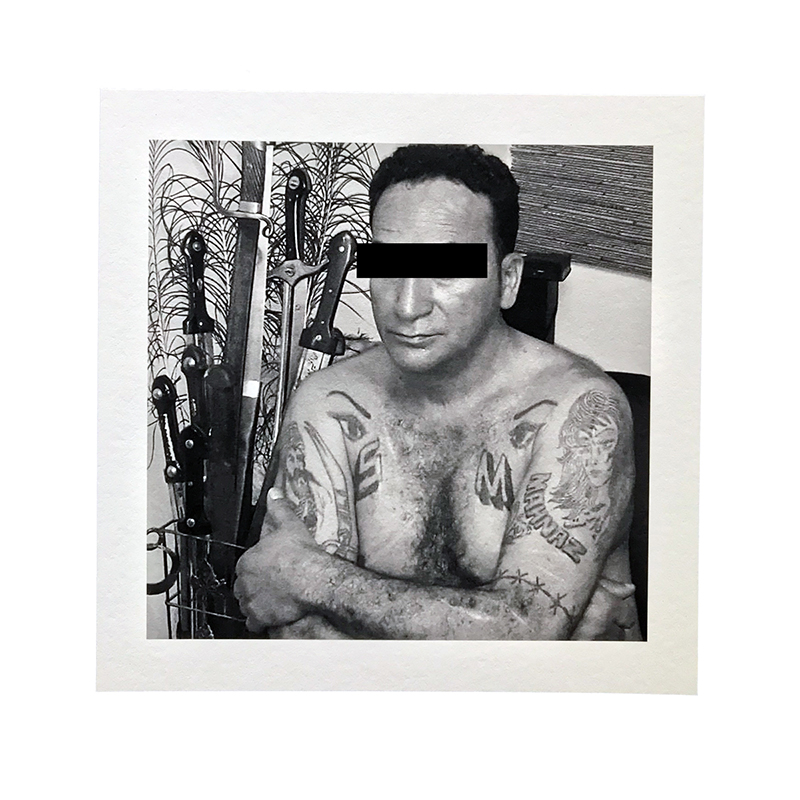

Many of the photos show how these men come head to head with the police. One man is pictured after a drug trafficking raid, held by a masked officer on either side of him as they expose his tattooed torso and announce his crimes over a megaphone in an attempt to highlight the connection between body art and crime.

When it was first released, Crime Wave Tehran generated a large wave of interest online, stemming largely from the fact that the book is a first of its kind. Khojastehpay’s publishing company, 550 bc, now boasts over 21,000 followers on Instagram.

“Many Iranians had no idea this existed in Iran,” Khojastehpay says. "It’s a taboo in Iran or the Middle East to talk about it in general.”

Khojastehpay recalls how Iranians expressed how strange it was that the criminal underworld he had brought to light was so little known within the country. One person praised the way his work keeps Iranian culture "intact" and how it avoids the "cliches and Western trends and romanticised ideas of the Middle East".

“In general many people were stunned to realise Iran has gangsters of this size and signature look,” said Khojastehpay.

The book project began in 2016, when Khojastehpay came across an Instagram profile showing a photograph of an Iranian man with prison tattoos. This intrigued him as he was aware that tattoos are a taboo in Iran, and usually associated with criminals. He then got into contact with the person behind the Instagram account who gave him more details about this man’s story and sent him some photographs.

Intrigued by the lives of these men, he dug deeper into the stories delivered by his friend and was soon sent more photos of them to add to his growing archive. He began searching for references in Iranian media archives and online, coming across news reports about some of the men he had by then encountered.

Poetry of the underworld

As his research developed, he realised that the stories of these men had not been previously told in media or arts. More importantly, he discovered that the way they represented themselves on social media and in their daily lives was in sharp contrast to the way they were shamed and vilified in the Iranian media.

A softer side of the men pictured throughout Crime Wave Tehran is shown in subtle ways. Some of their tattoos depict the names of lovers, and Persian poems about heartbreak and loneliness.

One such poem, inked across the back of one man reads: “Do not break my heart, even though you broke my heart in the past, do not break my heart. Now trust is just a fairytale.”

In another photo, a man’s tattooed eyelids read “shab” and “bekheir,” meaning “goodnight” in Persian.

'The narratives around crime and criminals are heavily influenced by the journalists’ responsibility to the law and the legal system of the country they are reporting in.'

- Mahmoud Fazal, crime journalist

Khojastehpay’s editing focuses on the individuals, their facial expressions and body language, and alludes to their personalities and humanity.

Embedded into the portraits are also images of crime scenes depicting violence, from a blood splattered floor in a jewellery shop, to CCTV footage of what appears to be a bank robbery.

Brotherhood between the men is also depicted, particularly in one photograph of three men standing shoulder to shoulder in prison, smiling into the camera of a smartphone that was smuggled in, according to the accompanying text.

“I changed the derogatory context Iranian state media displays and talks about these individuals and tried to show a more poetic, respectful way,” said Khojastehpay.

The reason for this disparity, says crime journalist Mahmoud Fazal, whose essay “Theatre of Cruelty” appears in the opening pages of the book, is that the narratives around crime and criminals are heavily influenced by the journalists’ responsibility to the law and the legal system of the country they are reporting in.

“But Pouria’s work is untouched,” Fazal told MEE. “The so-called criminals document themselves in the way they wish to be represented and viewed. We are offered a glimpse into their world through their eyes.”

Tattoos and taboos

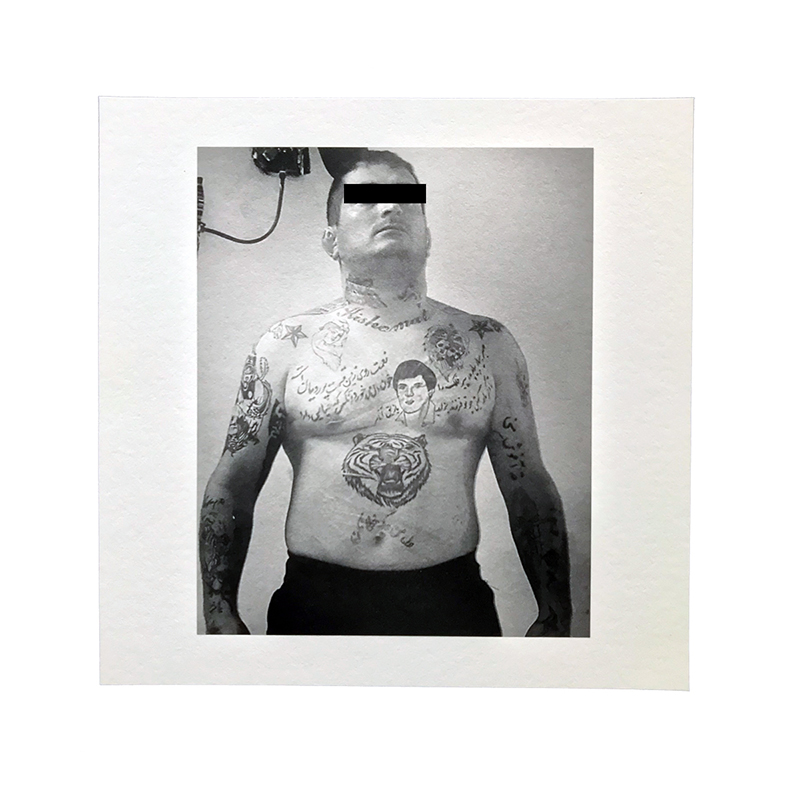

One striking visual element of the photographs is the tattoos of the men pictured. Tattoos are not an uncommon sighting in Tehran today among young people, but there are still negative associations with the art, linking it to criminal activity.

Although having tattoos is not strictly forbidden by law or by religion in Iran, tattoo artists are regularly arrested and football players are asked to cover their arms when playing publicly or run the risk of being dropped from the national team.

In Crime Wave Tehran, a selection of images from media reports show police officers displaying the bare, tattoo-covered torsos of the men upon arrest for the photos, which are then printed in news reports.

These tattoos are very different to those you might see on young men in the affluent northern suburbs of Tehran, which tend to be in the classic western style of roses, skulls, and the like.

Some tattoos on the men in this book include religious symbols rooted in Shia visual culture, such as portraits of Imam Ali and text reading “Ya Ali” in Persian.

Another is a cropped close-up of the neck and chest of a man wearing a pendant inscribed with Vanyakad, a verse in the Quran read for protection from the evil eye. Images of Imam Ali also appear on the walls against which the men pose in front of.

Poetry also features strongly in the tattoos of the men in the book. One reads 'zakhmy tar az hamishe' meaning 'more hurt than ever' in English

Aside from the religious element, other tattoos include animals such as tigers and birds of prey, nods to the Persian empire in the form of text reading "Mada" or the Medes, an ancient Iranian people, as well as profiles of men and women resembling Persian miniatures.

Khojastehpay describes some of this imagery as an embodiment of Iranian tattoo culture. “Most of the tattoos are done by underground tattoo artists in their own social circles. Persian miniature tattoos have been common for decades in Iran, mostly made popular by pre-revolution wrestlers,” says Khojastehpay.

Poetry also features strongly in the tattoos of the men in the book. One reads “zakhmy tar az hamishe” meaning “more hurt than ever” in English and another, “dele man daryae”, meaning “my heart is an ocean”.

Teardrop tattoos are also common, which can be used after someone has experienced some form of grief or loss, suggests a tender core to men with the burly exteriors.

"I think the teardrop tattoos some depicted gangsters have are my favourite," Khojastehpay says. "When it’s just an outline, it can mean mourning someone close to them that died by violence, to seek revenge for this person, or for ‘gunah’ - sins. When it’s filled black, it often means that one has killed or has [finished] a lengthy prison sentence."

Saviours and martyrs

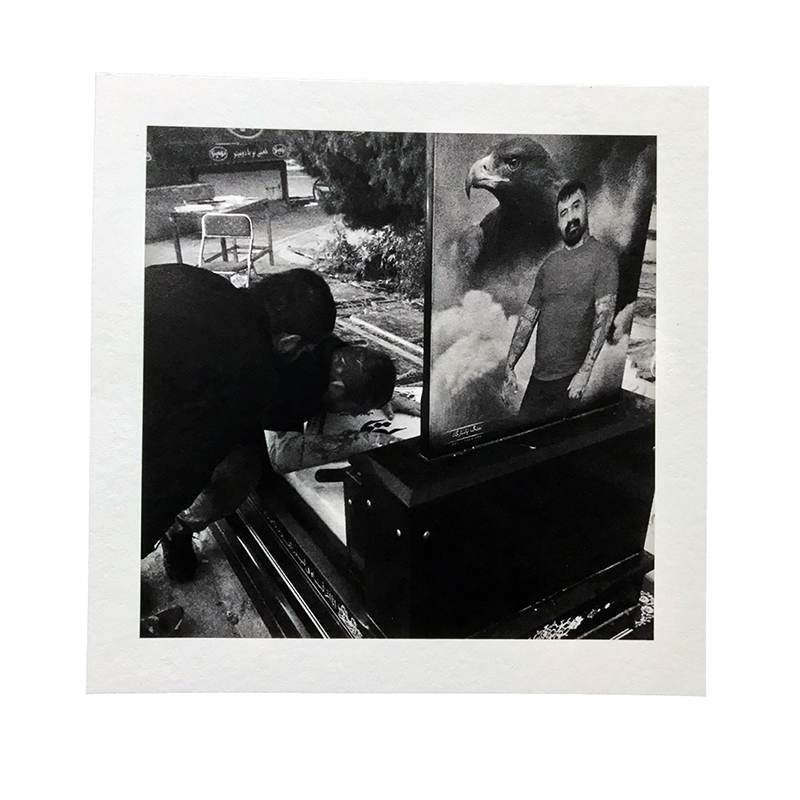

While some of the men in the book like The Eagle may have become infamous for their involvement in organised crime, in their own communities they were seen as Robin Hood figures.

“The give money back to the neighbourhoods they are from,” Khojastehpay told MEE. “They recruit from these areas too. So they are often praised as saviours, and when they pass, they pass as martyrs.”

He details how following his murder, The Eagle turned into a martyr-like figure for many disenfranchised citizens in Iran. A huge gathering turned out to his funeral, carrying his casket through the streets and protecting it until they reached the cemetery.

One of the photographs from the print series Gangstehran, shows an artwork that was created by the followers of Moradi (The Eagle) to commemorate him after his death.

Khojastehpay is keen to protect the identity of the men in the book for fear that they, or their families, may face repercussions, hence why many of the photos feature blurred eyes, and shots are taken from the neck down.

His anecdotes reflect the level of trust and intimacy he has with some of them, and through this he is able to paint a picture of the man behind the gangster persona, the lives they lead, and where they like to hang out – from bath houses and tea houses, to Islamic shrines.

“One of them has a large Iranian garden known as a bagh [usually not attached to a house] where they meet in the evenings,” Khojastehpay tells MEE.

Curating the book

As a research artist, and editor of the book and print series, Khojastehpay’s work was much more than simply sourcing and curating. After trawling through hundreds of social media posts, media archives, and photographs sent to him through contacts, he collated a large number of images, many of which were of poor quality.

Committed to editing the photographs to produce a unified body of work, Khojastehpay made the necessary technical enhancements, and rendered most of them black and white.

“This editing took a lot of time, but was crucial to give the viewer the idea that this was all taken by one hand, like a photo documentary series,” he explains.

Some of the men featured in the book told Khojastehpay that, although they didn't oppose its publication, they couldn’t quite understand why he put it together.

Others such as gangster HB, who recently passed, reached out to him personally, Khojastehpay says. “He wrote me over Instagram saying ‘damet garm soltan' [an expression used to express significant appreciation]."

HB roamed in similar circles to The Eagle, but many of his tattoos had been blacked out, which is believed to be a sign of reformation. His tattooed tear under his eye remained intact.

The nuances of living a life of crime come through boldly in Khojastehpay’s work, who shows us how hardened criminals are also fathers, brothers, and respected leaders. They can love their country and their faith, and fend for their communities.

'In the criminal world...our willingness to sacrifice for one another is what gets us through life'

- Mahmoud Fazal, crime journalist

Fazal, the journalist who was himself a former member of an outlaw motorcycle club in Australia, says there is a strong sense of comradery among these groups that not many people realise.

“In the criminal world, the central tenant is that we are all in this together - right or wrong. So it’s an old humanistic idea, relying on each other, not the state, on culture, not the faith - our willingness to sacrifice for one another is what gets us through life,” he says.

Crime Wave Tehran offers an unadulterated view of this multifaceted segment of society, carefully and respectfully curated to present myriad views of humanity.

In the same way, the book also represents a grey area in our understanding of Iran as a country and its people, which is all too often painted as black and white, good versus bad, revolution vs the Pahlavi dynasty, modern versus traditional, Islam versus secularism.

In reality, whether on the fringes of society or not, life is much more complex, murky, and subtle.

Crime Wave Tehran, edited by Pouria Khojastehpay in respect towards the individuals featured, is currently out of print but more information on his work that involves gangsters is available via 550bc.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.