Racism in the Middle East: The Arab films and TV that promote hatred

In September 2005, nearly 2,500 Black Sudanese asylum seekers in Egypt began protesting at their destitute conditions. Men, women and children started to camp at the park in Cairo’s Mustafa Mahmoud Square, part of the middle-class neighbourhood of Mohandessin.

Marginalised by the authorities, their demands were simple: give them refugee rights; or let them be resettled in a different country. They were ignored, so refused to leave the space.

A Bullet in the Heart (Rosasa fi al-kalb) from 1944 (screengrab)

On 30 December, the police violently waded in to clear the square. By the end of the raid, according to official reports, at least 20 unarmed Sudanese citizens had been murdered, including women and children. Other reports put the number at three times that or even higher. The massacre was largely overlooked by the Egyptian media and the public and quickly forgotten.

One week later, I was walking down a street in the affluent Cairo neighbourhood of Hadayek El Qubba, which housed a school for Sudanese refugees. Several teenagers were leaving at the end of the day. Then, a group of young Egyptians ganged up on them, before singling out one kid who was smaller than the rest. They separated him from the rest of the group and started circling him as they embarked on a tirade of racist mockery.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

There was one word that the Egyptian hooligans kept calling him: “Othmana”, a feminine derivative of “Othman” and a name used in a racist context for several decades thanks to Egyptian cinema.

How racist caricatures are born

These incidents came to mind in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the subsequent protests and condemnation worldwide, including across the Middle East and North Africa.

How groups in society perceive each other is framed by different factors, including upbringing and learned experience. Another is the influence of media and entertainment. There was an irony, then, in how some sections of Egyptian society tried to show solidarity, especially online, with Black Americans and the #BlackLivesMatter movement.

That’s because no other ethnicity has been belittled and ridiculed in Arab entertainment, which is dominated by the Egyptian industry as the region’s most populous nation, as much as Africans, from Arab-language films of the 1930s to Hollywood blockbusters in the present day.

Before Sudanese refugees arrived in Egypt after the country’s civil wars, Egypt’s Black population was chiefly comprised of Nubians from northern Sudan and southern Egypt, who had long resided on the banks of the upper Nile. They were estimated to constitute around three percent of the country’s population by 2015.

From the early days of Egyptian cinema during the 1930s, Nubians were cast in subordinate roles, such as servants or concierges, who were either invisible or else there to be mocked at; meek, resourceless people, with little intelligence, little talent, little agency.

As Viola Shafik wrote in Arab Cinema: History & Cultural Identity in 1998: “The two Nubian languages have not been used in a single film. Even visually the Nubian minority has been misrepresented.” For decades, any Black male character was always known as “Othman,” a cast extra whose sole function was to cheer on the lighter-skinned protagonists.

"El-Kassar positioned this black character within the Egyptian national family,” writes Alon Tam, at the University of Pennsylvania, “even pitching him as an all-Egyptian figure. At the same time, he undermined this position by marking Othman's skin colour and accent as inferior, and by associating him with other ‘foreign’-Egyptians.”

A rare exception was the widely popular character of Othman Abdel-Basset, the brainchild of comedian Ali El-Kassar (1887-1957), from 1935 until 1944. El-Kassar himself was not Nubian: born in Cairo, he mingled with the city’s Nubian community before he invented a racial caricature, complete with cracked accent, coy body language and reserved demeanour.

Othman Abdel-Basset became the most well-known Black character in Egyptian pop culture, giving Nubians a spectrum of emotions rare to the Arab screen. It was one of the very few - if only – instances of a Nubian character taking centre stage in mainstream Egyptian film.

To El-Kassar’s credit, he strived to create a working-class hero, ascribing him jobs - such as pie-seller or government employee - that differed from the usual servant-concierge ghetto. And there’s undeniably great humanity and playfulness in the character.

But Abdel-Basset still suffered from the cliches that have addled Black characterisation since, shaping how many Egyptians have perceived Africans for decades to come.

By the 1960s, when Nubians had been displaced in the wake of dam construction, first under the British protectorate and then the Egyptian government, Black characters were still relegated to the periphery of the screen. Blatant racist mockery had intensified and become the norm.

Even to be perceived as dark-skinned could stall a career. Ahmed Zaki (1949-2005) became one of the most popular stars of his generation - but in his early days, producers were reluctant to cast him, most notably in the classic adaptation of El Karnak (1975), despite being backed by director Ali Badrakhan. The role eventually went to the lighter-skinned Nour El-Sherif.

The examples continue into the 21st century. In the 2001 feature Africano, directed by Amr Arafa and starring Ahmed El-Sakka and Mona Zaki, one character shouts: "Is there a power cut in there or something?" as a group of Africans enter a nightclub.

“Your night is as black as your face,” the titular protagonist of Muhammad al-Najjar’s 2005 comedy, Ali Spicy, tells an escort hired by his uncle. “If you turn off the lights, nobody would see her.”

According to a study by the Border Center for Support and Consulting, 51 Egyptian films between 2007 and 2016 featured stereotypical depictions of Africans.

Racism in the digital age

Casual racism is not just restricted to cinema: with the explosion of TV and then digital platforms, so it has also spread to smaller screens.

In the 2018 comedy Azmi We Ashgan, Africans are depicted as uncivilised servants who practice sorcery (there’s also a very liberal use of the n-word).

In 2019, the prank show Shaklabaz (above), depicted TV comedian Shaimaa Seif wearing blackface to play an uncouth Sudanese woman on a congested minibus

And Egyptian actor Maged El Masry told an anecdote during a talk show about being set up with a group of African girls whom he instantly kicked out of his car.

But such racism is not restricted to Egypt.

In Tunisia and Morocco, it's rare that you will see Black TV anchors or presenters: not only does this fail to reflect the countries' ethnic composition, it also stops younger Africans from trying to enter the profession. There is also Nasser al-Qasabi, playing the primitive simpleton in the Saudi Arabian sitcom No Big Deal (Tash ma tash). The Kuwaiti series The Block of Jokes (Block Ghashmara) also had one episode where its two leads donned blackface, playing a pair of gregarious, uncivilised desert dwellers.

Indeed, it is blackface that is the most glaring example of racism in MENA entertainment. One might expect the younger generation in MENA to reject such archaisms, as practised by legendary action star Farid Shawky in the period drama Antara Ibn Shaddad (1961).

Not so: it has simply been repurposed for the 21st century. In the last few years, blackface has surfaced in the music videos of Egyptian singer Boshra and the Lebanese star Myriam Fares. Online, there was a resurgence in recent weeks as Blackfacing Arab actors and singers took to social media and mistook fetishisation and cultural appropriation for solidarity: culprits included Tania Saleh, Moroccan actor Mariam Hussein, and Algerian actor and singer Souhila Ben Lachhab.

In January 2020, Black Algerian Khadija Ben Hamou was subjected to racist abuse online when she was crowned Miss Algeria. One commentator wrote that he initially thought “she was a man” and that her face “is hideous".

In 2020, in Arab entertainment, Blackness is still presented as something that is ugly and dangerous, or else hip, cool and to be crassly appropriated. In this respect, parallels can be drawn with the West’s attitude towards the Middle East, which historically encompasses both orientalism and reductivity, such as the Hollywood terrorist bad guy.

Black “characters”, if you can call them as such, are not even fleshed out: beside the historic servants-concierge-style roles, Black characters are now reduced to hysterically tall dudes (usually Sudanese), as in the 1988 Egyptian play Alabanda; or hip and cool US-inspired rappers. Seldom does a Black character, even in blackface, have a role that lasts more than a few minutes.

Change in arthouse cinema?

One bright spot in this reprehensible chapter of modern Arab cultural history is a slow but increasing public awareness of racism.

El Masry was forced to make a public apology amid a social media outcry and the show was suspended by the Higher Council of Media. There were also no instances of Blackfacing or racial mockery of Africans during this year’s Ramadan TV season.

And in wider society, incidents of bullying and abuse of Africans across the region have resulted in the arrests of their preparators. Tunisia, for example, set a regional precedent in 2018 by criminalising racism.

There are notable attempts at Black characterisation, such as Rahil in Nadine Labaki’s 2018 Oscar-nominated drama Capernaum (2018), an illegal immigrant worker, as played by Eritrean refugee Yordanos Shiferaw.

The recent rise of Sudanese cinema is encouraging, including Marwa Zein’s Khartoum Offside (Oufsaiyed Elkhortoum), Amjad Abu Alala’s You’ll Die At Twenty and Suhaib Gasmelbari’s Talking About Trees, winner of the best documentary award at Berlin in 2019. A new generation of African Arabs have the confidence and expertise to finally tell their stories.

But such gains are limited. The role of Rahil failed to deviate from the often-arthouse perception of Africans as the long-suffering exotic stranger. The Sudanese wave, while artistically strong, is confined to the niche, limited art-house circuit (it’s also worth noting that too many serious-minded and independent MENA films fail to integrate Africans in their stories).

For a tangible shift in perceptions and attitudes to occur, African film-making needs to be integrated into the mainstream, with more Black agency in front and behind the camera.

For nearly a century, Africans have been Arab cinema’s disposable extras, be they invisible, blackface objects of ridicule, primitive shamans or exotic American rappers.

No representation means no acknowledgment of existence. Meanwhile, the Egyptian government continues to confiscate the last of the little remaining land of the country’s Nubians who are still demanding the right of return.

The role of slavery

In 2006, one year after the Mustafa Mahmoud incident, I chaired a public film discussion. The subject of discrimination against Egypt’s Sudanese community arose and I couldn’t help but mention the massacre as an example of racism.

The discourse did not go well: half of the audience said that the “lazy” Sudanese had it “coming to them” for “polluting” public property, and also that the government did not have the economic means to support them. The other half claimed that the number of deaths was lower than reported. Everyone there denied that the Sudanese suffered from any form of discrimination in Egypt.

And this, for me, surmises the issue at the heart of the Arab world’s anti-Black racism: self-righteousness. In Egypt and elsewhere, we fail to confront our hatred and bigotry, our ignorance and condescension.

The persistence of Black marginalisation in Arab entertainment is a byproduct of governments’ reluctance to acknowledge the discriminatory measures that have been adopted against Africans for centuries.

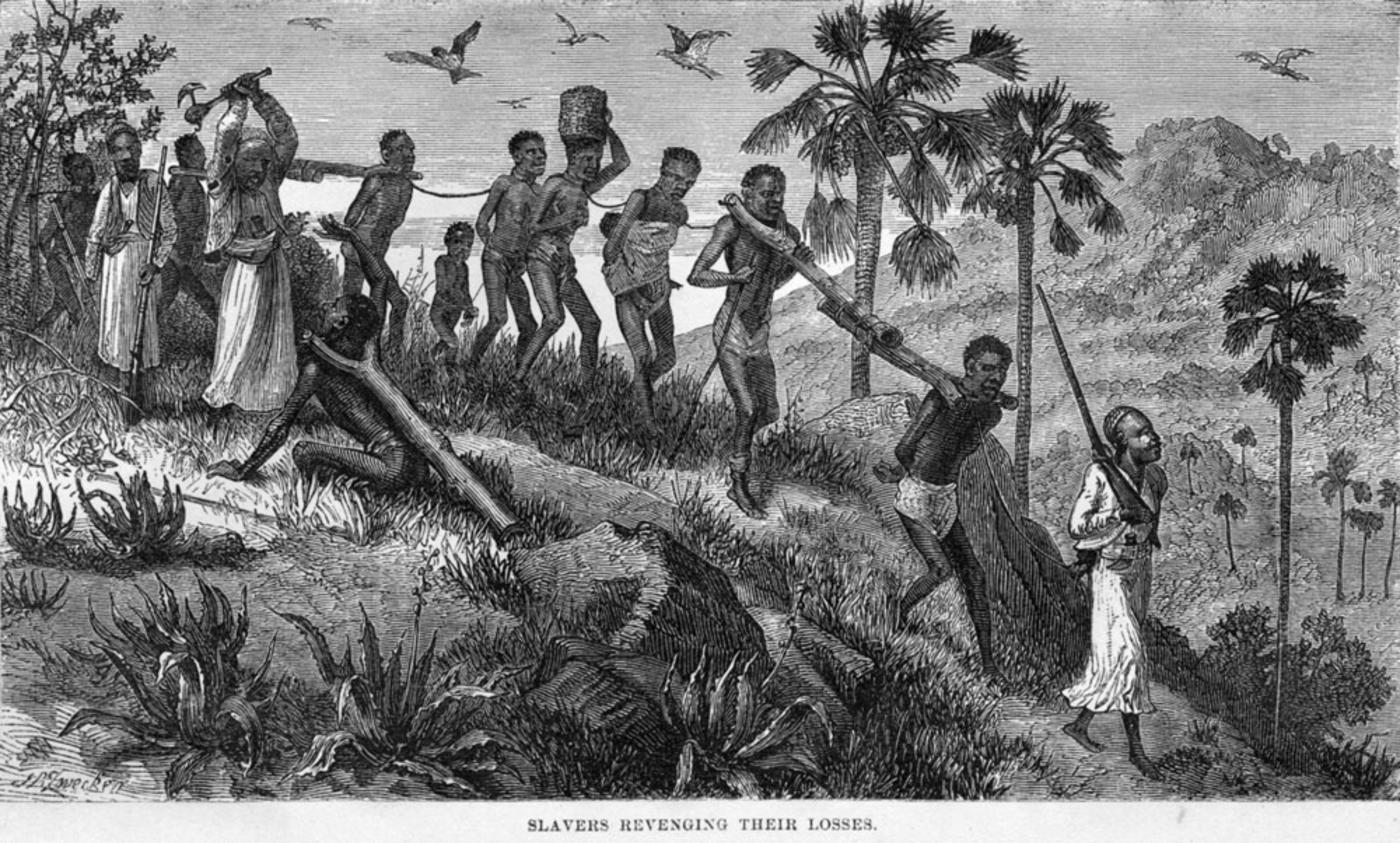

The history of African slavery in the Middle East and North Africa is less well known than that perpetuated by Europe and the United States, but it has a longer history, dating as far back as the 8th century. Some writers estimate that 17m East Africans were enslaved and taken to the Gulf as well as what are now modern-day Morocco and Egypt

The trade was still thriving during the 19th century. In Oman, slavery was only abolished in 1970; it was only criminalised in Mauritania and Western Sahara in 2007 and 2010 respectively.

Endemic racism was the foundation of the trade, which used human life as mere economic chattel. By indulging in blackface, the Arab entertainment industry perpetuates such prejudices.

We may cast a critical eye on America for its centuries-long systemic racism - but we also need to start looking at the mess in our own backyard first of all.

The views expressed in this opinion article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Joseph Fahim is an Egyptian film critic and programmer. He is the Arab delegate of the Karlovy Vary Film Festival, a former member of Berlin Critics' Week and the ex director of programming of the Cairo International Film Festival. He co-authored various books on Arab cinema and has contributed to numerous outlets in the Middle East, including Middle East Institute, Al Monitor, Al Jazeera, Egypt Independent and The National (UAE), along with international film publications such as Verite. To date, his writings have been published in five different languages.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.