'Thunderbolts and terror': How historic earthquakes destroyed Roman Antioch

When it came to describing the devastation wrought on Antioch by the earthquake of 526, the Byzantine chronicler John Malalas told a tale of fire and brimstone not unlike that of February 2023.

“The surface of the earth boiled and foundations of buildings were struck by thunderbolts thrown up by the earthquakes and were burned to ashes by fire, so that even those who fled were met by flames,” he wrote.

“As a result, Antioch became desolate, for nothing remained apart from some buildings beside the mountain. No holy chapel nor monastery nor any other holy place remained which had not been torn apart. Everything had been utterly destroyed.”

“In this terror,” the native of the Levantine city said, “up to 250,000 people perished.”

The buildings that weren’t destroyed by the earthquake were consumed by the fires that burned afterwards.

Malalas records the discovery of people under the rubble who went on to die. He recounts people fleeing with their possessions only to be robbed.

He says, though, that God’s will is revealed when those robbers – including a man named Thomas, who spent four days “stealing everything from the fugitives” – all “died violently”.

“Other mysteries of God's love for man were also revealed,” the chronicler, as translated by Exeter College, Oxford Fellow and scholar of Byzantine and Greek literature, Elizabeth Jeffreys and team, continues.

“For pregnant women who had been buried for 20 or even 30 days were brought up from the rubble in good health. Many, who gave birth underground beneath the rubble, were brought up unharmed with their babies.”

Children were brought from the rubble after 30 days. On the third day after the earthquake had brought Antioch to the ground, “the Holy Cross appeared in the sky in the clouds above the northern district of the city, and all who saw it stayed weeping and praying for an hour.”

“The emperor,” Malalas wrote, “provided much money for the cities that had suffered.”

Greek origins

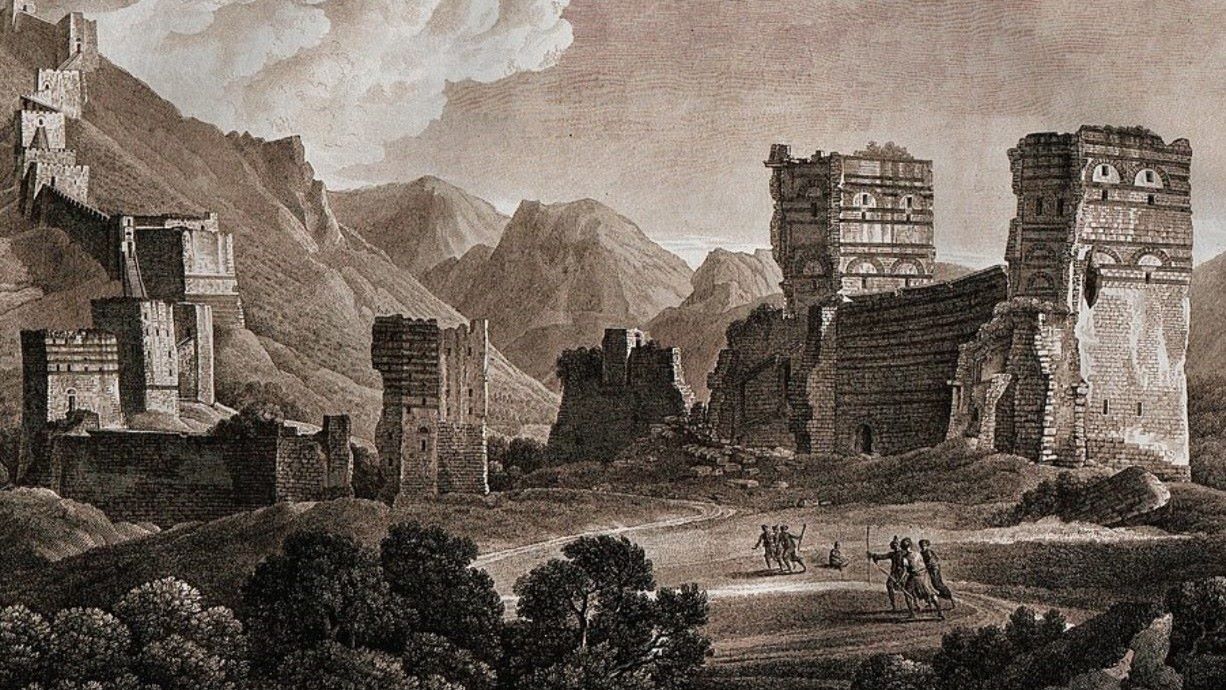

Antioch stood where part of the modern Turkish city of Antakya now lies and has been flattened by powerful earthquakes in the past – and then rebuilt. The site lies atop a convergence of three tectonic plates: the African, Arabian and Anatolian.

It is this convergence that resulted in the twin earthquakes of 6 February 2023, which have killed more than 42,000 people at the time of writing, and have once again razed large parts of Antakya to the ground, recalling the destruction and miraculous rescues recounted by Malalas.

The earthquakes of 115 CE, in which 260,000 people are estimated to have died; and 526, which Malalas wrote of, were particularly significant for Antioch, though the ancient estimates for fatalities in both earthquakes are thought to be wildly exaggerated.

In fact, the sixth-century earthquake was the first in a string of events – including a Persian invasion and a pandemic – that saw Antioch go from being one of the most important cities in the Roman empire to a more modest town known mainly for its unusual brands of Christianity.

Who were the people who lived through these disasters, what did the region look like at the time and what became of it in the wake of such destruction?

Antioch was originally the product of a world turned upside down by the astonishing series of conquests made by Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE).

Following the conqueror's death, the lands he had won, which stretched from Greece and North Africa through Persia and Punjab, split into four kingdoms.

'It (Antioch) was a fun-loving place. They loved their entertainment. It had beautiful suburbs for excursion'

- Anthony Kaldellis, University of Chicago

One of Alexander’s generals, Seleucus I Nicator, founded Antioch on the mouth of the Orontes River, about 300 miles north of Jerusalem and 20 miles inland from the Mediterranean.

From that Macedonian beginning, Antioch passed into the domain of the Roman Empire, which took full control of the city in 25 BCE.

According to Anthony Kaldellis, a professor at the University of Chicago and author of the forthcoming The New Roman Empire: A History of Byzantium, Antioch then grew to become the fourth-most important city in the Roman Empire behind Rome, Constantinople and Alexandria.

Syria, of which Antioch was the chief city, was agriculturally prosperous. There was a lot of wheat, olive oil and wine production. In the centuries following its accession into the Roman empire, settlements expanded into the countryside and new villages were created.

Stone began to be used more often in construction. The rooves of houses started to be tiled rather than thatched, a sign of growing prosperity. “Antioch was a pleasure city with a bad reputation,” Kaldellis told Middle East Eye. “It was a fun-loving place. They loved their entertainment. It had beautiful suburbs for excursions.”

The Roman Emperor Trajan and his successor Hadrian were caught in the earthquake of 115 CE, though they escaped with minor injuries and later began a programme to rebuild the city. Around that time, Antioch’s population was still mostly pagan.

A centre for Christianity

There were people who worshipped Greek gods and people who worshipped Roman gods and some who worshipped local Syrian gods.

A significant number of Jews lived in Antioch from its foundation; according to the Bible’s Acts of the Apostles, “It was at Antioch that the believers were first called Christians.”

Saint Paul, who died in the year 64 or 65 CE, was from nearby Tarsus, which was at the heart of the area affected by the earthquake of 115 CE. Not long after his death, Antioch – and Syria generally – became known for its Christian cults.

The early Christian, Ignatius of Antioch, was arrested by Emperor Trajan, at a time when Roman emperors were still pagan. It was Constantine, who ruled the empire from 306 to 337, who became the first emperor to convert, almost two centuries later.

Despite this religious upheaval, Antioch remained an economic hub; a lot of trade came into the city from the east.

It was also a strategic node for Roman defences looking towards the Persian or Parthian empires in the east and a command headquarters for the eastern border located not exactly on the border, but close to it – which is why Trajan and Hadrian were at Antioch during the earthquake of 115.

Many significant figures emerged from Antioch, even before the extension of universal Roman citizenship in 212.

In the 2nd century, Tiberius Claudius Pompeianus, who came from a relatively humble family in the city, married the daughter of the emperor Marcus Aurelius.

A famous general, Pompeianus served as the main inspiration for the fictional Maximus, Russell Crowe’s character in the film Gladiator. Hollywood being Hollywood, though, in the film version, Maximus is not from the Middle East, but from Spain, in western Europe.

Pompeianus was offered the imperial throne three times, turning it down on every occasion. In 182, Lucilla, Pompeianus' wife, organised a failed attempt on the life of her brother, Commodus (immortalised by Joaquin Phoenix in Gladiator), who had succeeded his father Marcus Aurelius.

Commodus had his sister executed but Pompeianus, who had not been involved in the plot, was spared.

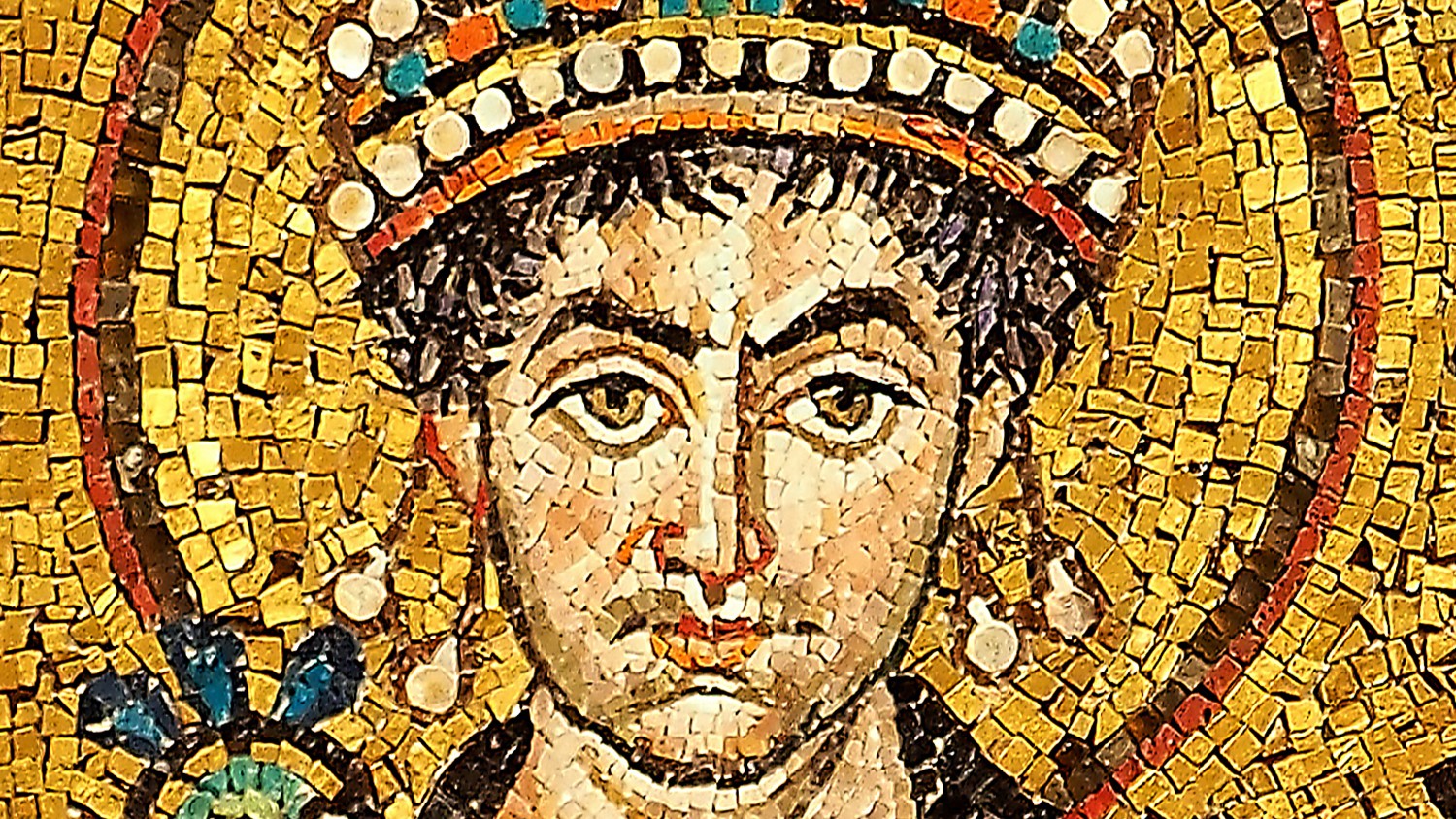

In 395, the Roman emperor Theodosius I died, leaving the western half of the empire to one of his sons and the eastern half to another. The west was ruled from Rome and the east from Constantinople but, Kaldellis said, “there only ever was one empire”.

In the fifth century, the western empire fell and became a series of barbarian kingdoms, some of which paid lip service to the idea that they were still part of an empire ruled from Constantinople. This eastern empire has become known as the Byzantine empire - “the last Romans”, in the words of Paul Cooper.

By the sixth century, the people in the region around Antioch were known as Syrians, but this was not an ethnic label. It could, for example, apply to Greeks, who made up a majority of the city’s population. About five million people lived down the Mediterranean coast from Syria to Egypt.

The majority of these spoke Syriac, a form of late Aramaic, the ancient language of the Middle East and one of the original languages of the Bible.

“Around 500, Antioch was very Christian,” said Kaldellis. “There were a lot of enthusiasts for Christianity… Ascetics and hermits, monasteries in the countryside.”

The Syrian ascetic Simeon Stylites was one of the most famous of these, spending 37 years living on a small platform on top of a pillar near Aleppo.

Built to withstand fire, not earthquakes

At the time of the 526 CE earthquake there were, according to Kaldellis, three main types of houses in the Roman Empire: elite villas, which were often in cities, had between one and two storeys. They were built over a wide area, with courtyards and fountains, rather than being built upwards. If they collapsed, their owners had the resources to rebuild them.

There were also small homes and apartment buildings that could often be four storeys tall and were very dangerous if lots of people crammed into them.

One primary source that gives an idea of what these buildings were like is a letter in which an occupant complains about the family who live above him. They keep a pig and its urine keeps coming down through the ceiling into his flat.

The buildings were mainly constructed of brick, stone and various kinds of mortar and concrete.

Elsewhere in the empire, the Hagia Sophia, the vast Greek Orthodox church in Constantinople, was built using a new type of concrete, and while earthquakes over the centuries have caused cracks in its dome, it remains standing nearly 1500 years after it was completed.

“They did think about building to withstand earthquakes, but by far the major concern was fires, because they used a lot of wood in their construction. Building laws in antiquity are concerned with fires,” said Kaldellis.

Earthquakes, though, were something that could be recovered from. “Earthquakes generally only have local impact,” Kaldellis told MEE.

“You don’t have apartment buildings that are more than four storeys. Towns and cities are less dense… Emperors rebuild, tax breaks are set up. Roman emperors are responsive – they didn’t have elections to win but they don’t want people to be angry or disaffected… Urban elites matter in the Roman world.”

In sixth-century Syria, though, this process was hampered, and the earthquake of 526 CE is an opening salvo in a series of disasters that devastates the Roman region.

In 540 CE, a Persian invasion saw Antioch burned to the ground and its surviving inhabitants deported by Khosrow, the Sassanian king of Iran, to a new city that he named “Khosrow’s better Antioch”. This new city was built by architects from the original Antioch.

Along with the surviving people, Antioch’s surviving artwork, statues and other valuable objects were put onto boats on the Euphrates river and floated away into Sassanian territory.

The Byzantines were rebuilding the original Antioch – which had been renamed Theopolis, meaning “City of God”, in order to guard against further disasters – when the Justinianic plague hit.

This pandemic, which began in 541, is estimated to have killed anywhere between 30 and 50 million people, or about half the world’s population at the time.

Antioch was beset by further troubles, finding itself on the frontlines of the Arab-Byzantine wars for almost four centuries and later the conflict between Crusaders and Islamic forces.

“It probably never returns to the levels it was at around 500,” Kaldellis said, and the centre of the region moved from Damascus and then to Baghdad.

Antioch became a “backwater Christian town in the vast Islamic caliphate”, and a militarised frontier between Syria and the Anatolian plateau.

This journey away from the centre of history was not caused by the earthquake of 526 CE. But it did begin there, as the people dug through the rubble, looking for a path away from the pain and destruction around them.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.