Yasmeen Audisho Ghrawi: A warning to the UK from a daughter of dictatorship

Yasmeen Audisho Ghrawi arrives on her bike at Highbury Fields in north London, and splits open a packet of roasted almonds to share as she settles down to talk to Middle East Eye.

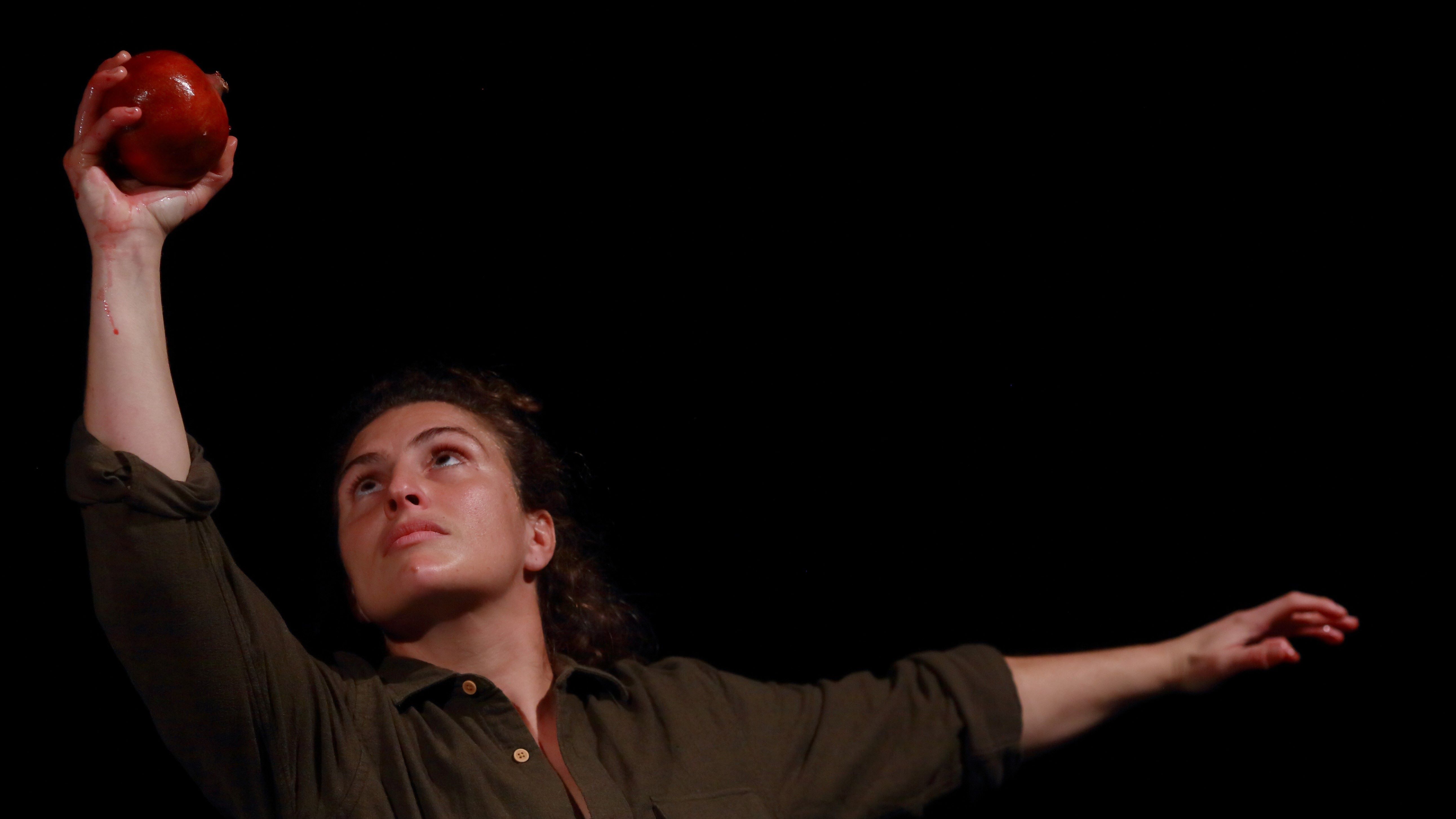

She is days away from the premiere of her solo show From the Daughter of a Dictator at Shubbak Festival of Arab arts in London.

Audisho Ghrawi has been on an odds-defying personal journey as an artist and performer who grew up in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, lived in Lebanon between two wars, and then moved to the UK as a political science masters student, before radically changing course to become an artist.

This creative journey has seen her work as an assistant director at the Royal Shakespeare Company, as a consultant to radical British filmmaker Ken Loach on The Old Oak, his latest, possibly final film, while also developing her comedy standup show with the No Direction Home comedy collective at Soho Theatre in London.

Audisho Ghrawi does not use words lightly; all are carefully chosen, then recalibrated, and she is not afraid to correct any misunderstanding about her meaning.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Her new show is highly personal, with elements of autobiography, physical performance, and comedy.

It speaks to her disquiet at seeing Britain’s democracy gradually slip towards authoritarianism. As an Iraqi who grew up under a dictatorship, it’s something she knows and fears.

A sense of dread

She describes a creeping sense of dread as she read the draft Police Crime Sentencing and Courts bill on the government website in 2021.

"They were referring to the 2019 Extinction Rebellion takeover of Central London - and then Black Lives Matter came out after the murder of George Floyd. So they use that rationale somehow to justify why the protest laws needed changing," she tells Middle East Eye.

“The way they worded is that, of course, we will protect the individual right to protest, but we also want to protect hard-working British citizens and to protect them from any disruption or nuisance.

“And also they’re proposing that the police can now essentially arrest anyone who was peacefully protesting on the basis that they are causing nuisance and disruption.

"And I remember reading that and getting a feeling in my chest, a visceral feeling. …And that visceral reaction immediately, instantaneously transported me to my time growing up in Baghdad.”

It was a reaction she rationalised as normal for someone like her who grew up in a dictatorship in Iraq, and she asked herself if she was being paranoid.

“Every conversation that I started to have with friends of mine who are very liberal, who are very educated, very worldly, some of who are activists, I would ask them about the proposed bills, specific bills, you know, this feels really dangerous. This feels like these are the incremental steps towards authoritarianism.”

A child under Saddam

Describing what it felt like growing up in Iraq in the 1980s and 90s under Saddam Hussein, she says that she always knew where the red lines were.

“I understood that there are things that you don't talk about: you don't talk about politics. Yeah, it's dangerous. From a very young age, I knew that this person has been disappeared.

"This person has been arrested because he was sitting in a cafe and somebody heard him say something. So, from a very young age, I knew that you shouldn't say anything because they'll come for your parents.”

She describes the experience of reading George Orwell’s 1984 when she first came to the UK 15 years ago as “almost like an autobiography of growing up in Iraq, from the perspective of the insider”.

Audisho Ghrawi, whose father was Syrian-Lebanese and mother an Assyrian Iraqi, took her chance to study abroad by going to Lebanon in 2000.

She puts it how her father saw it: “You don't come from a wealthy family. You're not going to have an inheritance, but you will have an education.”

Studying in Lebanon

While studying computer science, she began attending political science classes at the American University of Beirut.

“I started to take these political science classes and people were sitting there debating, talking.”

It was a new experience for Audisho Ghrawi, and she was hooked, switching to political science, even though she had no idea what would happen and did not tell her father about it.

When the US invaded Iraq in 2003, her sisters and mother fled to Lebanon to be with her.

“They left in a hurry. You're thinking that there's going to be a war like, like one of these fucking American wars and then they'll come back.”

But that was not to be. Two decades later her family is still in a crisis-torn Lebanon and is suffering like millions of other Lebanese and Syrians as a result of the economic collapse.

She last went to Lebanon to see her family a year ago. The artist explains the reality of life there for a lower middle class family.

“When I visited them last time, it was February. It was really cold. Two storms hit in the two weeks I was there. I only managed to take one five-minute shower because there was no hot water.

"There was no electricity. So we couldn't turn on any heating.

“It was so cold. And as I look around me, my mum has all these layers, and her shoulders are up. And I thought, if we are living like this, I don't even want to imagine what people who have less are going through now.”

Lebanon hosts more than a million Syrian refugees who fled the war, but many are now trying to leave the country to escape the crisis.

'I don't even want to say drowned. They were murdered...'

- Yasmeen Audisho Ghrawi

“It’s so desperate that people are doing an even more dangerous trip, trying to leave Lebanon to reach the shores of Cyprus. But nobody hears about this, obviously. I mean, we barely even hear about the hundreds of people that just drowned in the Mediterranean.”

She qualifies her statement about the recent capsizing of a crowded fishing boat that has left up to 500 people dead, including 100 children. “I don't even want to say drowned. They were murdered because the coast guards knew exactly that there was a boat in distress.”

The Greek Coast Guard claimed the migrants on the boat refused help, but survivors and rescue groups said their calls for help were ignored for many hours before the sinking.

Fleeing war

Audisho Ghrawi has herself lived through several wars in Iraq, and then in Lebanon. In 2006 the Israelis attacked Beirut, and the family had to flee the capital.

She describes it using the second person, a kind of distancing from the violent geopolitical events that shaped her life.

“These disasters or wars are following you because you leave Iraq [before the 2003 US invasion]. … But then you've got the Israeli attack [on Lebanon] in 2006. Yeah. So then you end up in London.”

Two days after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon ended in 2006, Audisho Ghrawi flew to the UK to begin her master's at the London School of Economics.

“I was sitting in classrooms where we were talking about social and economic development. And I was sitting there really hallucinating, thinking I would like to talk about de-development and how it happens overnight.”

She adds: “Somehow me coming just out of a war into a very elitist, prestigious university in this country, with all these grand theories that were being thrown around at that moment, they just felt dumb, they just felt hollow.”

“I was the frog… that was being dissected, I was the object of their study.”

A new chapter

At the end of her master's degree, she vowed never to return to academia. It was a turning point. Being a performer was an unimaginable dream until that point, but a new chapter began for Audisho Ghrawi.

“I always absolutely loved performance. I did it when I was in school. The first thing that I did when I entered universities, I looked for the drama club, but it never went beyond that,” she says.

“I never in my wildest dreams even thought about it. I don't have a vocabulary for working in the arts. I didn't grow up knowing that this is even a possibility.

“Many people used to tell me: are you a performer? Why don't you perform? As I was growing up, I'm like, ‘What the hell are you talking about? Don't you see the state of the world? What fucking performance? What is this frivolous shit that you're talking about?'”

Now, many years later, she has fully embraced the creative performer’s life, and while not an easy option, she has flourished in the kind of roles and possibilities it has given her.

'I feel like I want any medium. Every medium. I want the stage. I want the streets. I want TV, film'

- Yasmeen Audisho Ghrawi

Before the pandemic, Audisho Ghrawi was assistant director on A Museum in Baghdad by Hannah Khalil, set in 1920s Iraq and in the chaos following the 2003 invasion, working with Royal Shakespeare Company director Erica Whyman.

Recently she has worked as a consultant and casting assistant, working with Syrian actors, for Ken Loach on The Old Oak, about a pub in a poor ex-mining town that becomes a social hub for Syrian refugees.

“It was an amazing experience. It was one of the most important experiences of my life,” she says, describing Loach as “somebody who has such strong and clear values and political positions, and also to see how that is reflected in the smallest details, and the team of people around him and how they interact with each other."

The Old Oak was recently shown at Cannes Film Festival, where the welcome for Loach can be contrasted with his recent expulsion from the UK Labour Party amid claims that he supported groups proscribed by the party due to allegations of antisemitism.

His expulsion is a familiar story to many critics of Israel and supporters of Palestinian rights in the party under Keir Starmer.

Audisho Ghrawi sees her future path as wide open to new ventures, with many roads open to her.

“I feel like I want any medium. Every medium. I want the stage. I want the streets. I want TV, and film. Now that I've been opening these spaces for the last ten years, I'm just hungry for expression, for creation, for collaboration, for manifestation, you know?”

Yasmeen Audisho Ghrawi performs at The Lowry, Manchester, on Friday 30 June, and at Theatro Technis, London, 3-4 July.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.