A London dance production of Layla and Majnun reveals an ancient tale of love

LONDON – Qays, a young man, is so immersed in his love for the beautiful Layla that he quite literally loses his mind, earning him the nickname Majnun - "madman". In turn, Layla's parents forbid her from being with Majnun, due to his rather intense infatuation.

A stunning adaptation of Layla and Majnun at Sadlers Well’s Theatre in London is both a dance and a drama. Running until 17 November, it tells a story whose origins can be traced back to 7th century Arabia and the renowned Arab poet Qays ibn Mulawwah.

The reimagination of the classic, the first of its size in the UK, is the brainchild of American choreographer and director Mark Morris and is produced by his Mark Morris Dance Group, in collaboration with world-renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Ensemble and British artist Howard Hodgkin, who designed the set and costumes.

In an interview with Middle East Eye, Morris said the most compelling thing about the story of Layla and Majnun is the "profound, eternal, incorporeal love and devotion" it contains. "The legend is the genesis of the great music," he said.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Lord Byron, the 19th century British romantic poet, once referred to the story of Layla and Majnun as the Romeo and Juliet of the East, even though its oral tradition predates Shakespeare's tragedy by over a thousand years.

Relatively recent and varied re-tellings of Layla and Majnun include the 1971 song Layla by Eric Clapton, the 1973 Majnun Symphony by American composer Alan Hovhaness and the 1999 song taken from the album of the same name, Ya Majnun, by Syrian diva Asala.

A universal tale

The 70-minute transcultural performance at times feels busy, but at its core it is an ill-fated romance. Byron was right - similarities with Romeo and Juliet are not hard to find.

The structure of the dance production at Sadler's Wells sees the story divided into five acts: Love and Separation; the Parents’ Disapproval; Sorrow and Despair; Layla’s Unwanted Wedding; and The Lovers’ Demise.

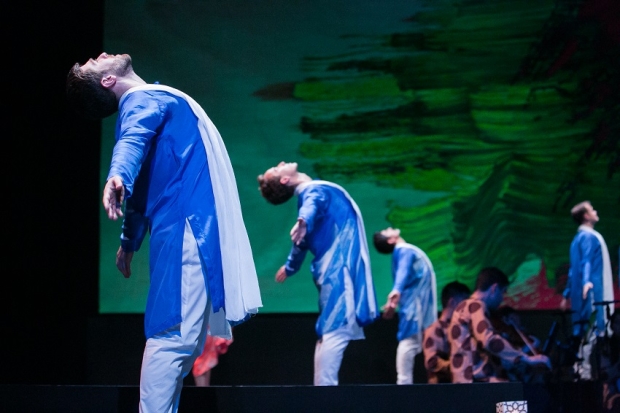

The 12 dancers sometimes appear to float across the stage, borne aloft by the soothing Azerbaijani music that fills the venue.

The musicians are centre stage as they play traditional Asian instruments and two singers are seated before them on what appears from a distance to be a plush divan.

Layla and Majnun are represented by different performers in the five different acts; a white scarf travels from male dancer to male dancer, indicating that he has become Majnun, while Layla is given an orange scarf.

Their movements mimic the poem as it’s sung by Fargana Qasimova and her father Alim Qasimov, a leading Azerbaijani mugham performer and one of the libretto’s arrangers.

Though they pine for each other, the young protagonists rarely - if ever - touch, underscoring the ill-fated nature of their relationship.

The remaining dancers take on various roles: parents, or perhaps friends, or perhaps even society. In one act, we see four Majnuns and four Laylas. This is a story both vast and universal, one that some say is less about earthly love and more about mysticism, spirituality and devotion to god.

They don’t need to touch much. It is about noticing and paying attention with all of one’s senses

-Mark Morris, American choreographer and director

“I distributed the danced roles of Layla and Majnun to indicate their passage through time and the maturity of the relationship,” Morris said. “They don’t need to touch much. It is about noticing and paying attention with all of one’s senses.”

An explosion of colours adds to the depth and warmth of the experience: the women are dressed in full-length dresses the colour of flames, the men in indigo and the musicians in gold and brown. A backdrop of enormous spirals of emerald and scarlet paint completes the spectrum.

Star-crossed lovers

The story of Layla and Majnun has permeated the Middle East and Central and South Asia for hundreds of years and is as such present in Hindu, Muslim, Sufi and secular oral histories.

Qays’s poem was later popularised by the Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi in the 12th century. In the original poem, the star-crossed would-be lovers meet and fall for one another as children.

Layla is later married off to a shallow, wealthier man while Majnun is left in sheer agony. He, in turn, becomes a hermit, committing his lonesome days to writing about his increasingly desperate love for Layla. The two never quite come together, despite repeated attempts to do so.

At Sadler's Wells, surtitles derived from the libretto illuminate this emotional landscape: "My only wish is to perish in the world of love," reads one. "If this were up to me I would never want anyone but you," another.

The narrative occupies a special place in Azerbaijani culture as well. The Morris adaptation is based on a 1908 opera libretto by Uzeyir Hajibeyli depicting the heart-rending story, which became the first musical score in Azerbaijan.

Before this particular production had its world premiere in California in 2016, the work had not been seen on this scale outside of Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan.

The performance opens with a gorgeous overture by Azerbaijani vocalists Kamila Nabiyeva and Miralam Miralamov, both dressed in crisp white shirts.

Alongside them are Rauf Islamov and Zaki Valiyev, who appear to be entranced by the music as they play the kamancheh, a bowed string instrument and the tar, a lute.

What follows is a glorious amalgam of Azerbaijani music sung in the style of mugham - Azerbaijan's most ancient form of music - and Western choreography and orchestration.

Scholar and musicologist Aida Huseynova, who worked on the adaptation as a consultant on the history of Layla and Majnun, told MEE: “This new arrangement is done with huge respect to the poetic rendition of the tragic story created by Muhammad Fuzuli [16th century Azerbaijani poet] to the music written by Hajibeyli, and to mugham, the treasure of traditional music of Azerbaijan.”

No appropriation

The transcendental performance is refreshed and enhanced, rather than weakened, by the mish-mash of cultural traditions. It’s a delicate balance to strike but Morris, who has created more than 150 works for his dance group, has mastered it. There is no cultural appropriation, only appreciation.

The eclectic dance alone brings to mind the movements of the whirling dervishes of traditional Sufi dancing, Koleda (or Balkan) dancing, and even ballet and ballroom dancing. It’s a gorgeous and gentle combination that never overshadows the music. There are hand-in-hand walks, twirls, hip twitches, and dramatic leaps and drops. The dancers take cues from the musicians and singers, frequently facing them as they perform.

The version, as I first heard it performed, seemed incomplete, gloomy, slow, and very beautiful

- Mark Morris, American choreographer and director

It was the Paris-born Chinese-American Yo-Yo Ma, and the Silk Road Ensemble, an international community of musicians, who decided to bring the Azerbaijani opera to Western audiences, following a proposal from Qasimov. When Ma first presented the performance to Morris, who he had worked with previously, he was not entirely convinced.

“The version, as I first heard it performed, seemed incomplete, gloomy, slow, and very beautiful,” Morris said. “Over time, with a few changes of orchestration, pacing and sequence, it formed into a better-balanced vehicle for a theatre production. I warmed to it as I listened more and learned more.”

It’s now been two years since Layla and Majnun’s world premiere. Since then, the performance has “grown and changed” even further, Morris said, adding that he finds its critical reception “very satisfying”.

The audience at Sadler’s Wells was indeed ecstatic. As the dance production came to an end, and the crowd erupted into applause and cheering, one woman exclaimed “Genius! He’s a genius!” as she gave a standing ovation. She was referring to Morris.

“Layla and Majnun are now mesmerising the audiences not only in their respective countries, but all over the world,” Huseynova said.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.