Human trafficker’s escape leaves survivors disillusioned and fearful

When Tekle learned that Kidane Zekarias Habtemariam, the head of a brutal human trafficking ring, was arrested by Ethiopian police in February 2020 and set to appear in court, he was elated.

The 29-year-old Ethiopian migrant in Libya says that he was tortured and starved for months in a warehouse in Libya at the hands of Kidane.

“Of course, I was happy. Kidane was responsible for so much death and suffering,” Tekle - who requested to speak under a pseudonym - told Middle East Eye over the phone from an undisclosed location in Libya.

“But I was naive to think we’d get any justice.”

The dejected man is still processing the news that Kidane - accused by scores of migrants of murder, rape and extortion - escaped police custody in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa a year after his detention.

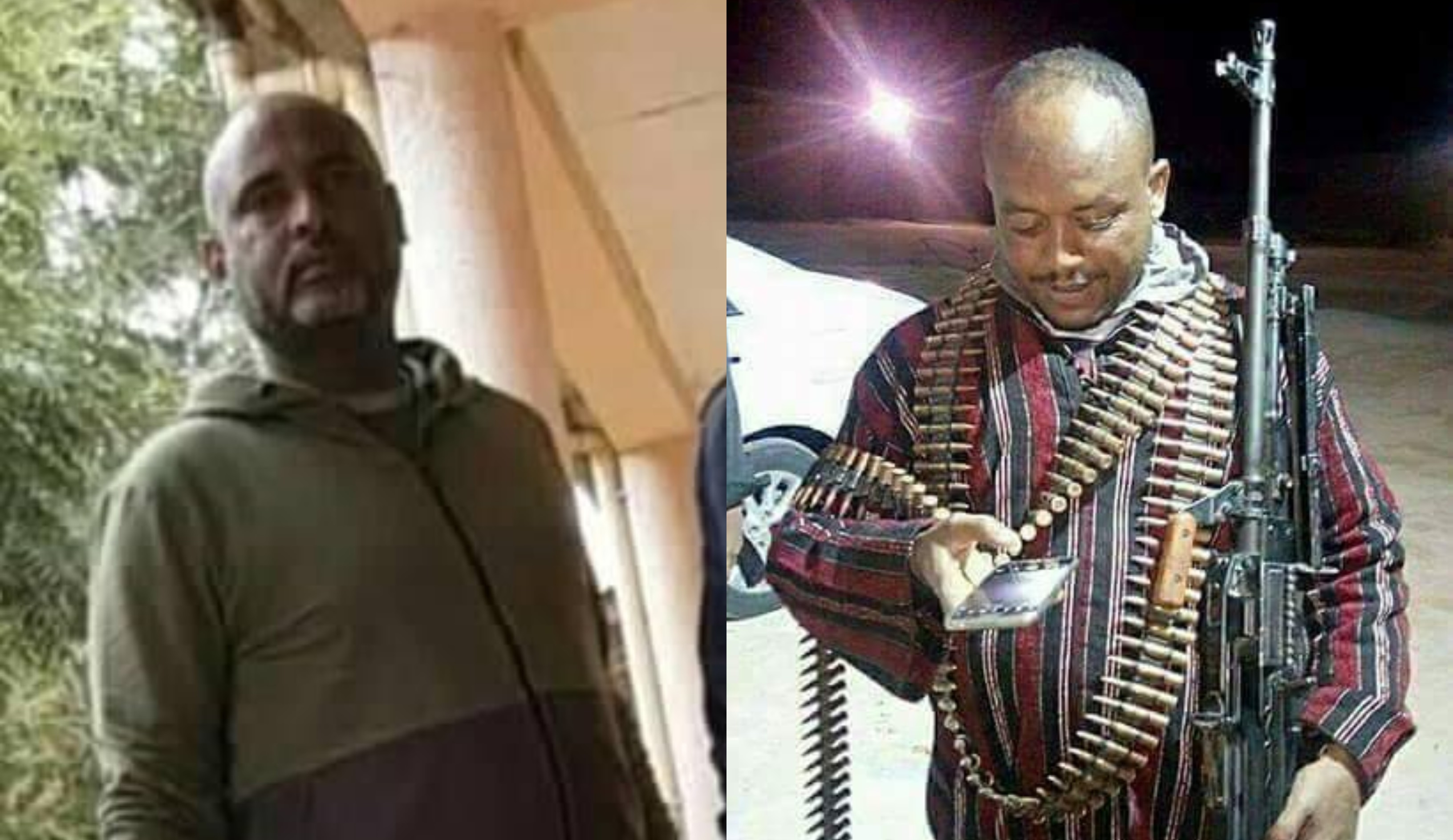

A middle-aged Eritrean national, Kidane is among the most wanted human traffickers in the world by law enforcement agencies on either side of the Mediterranean Sea.

Described by his victims as murderous and bloodthirsty, he is among several human traffickers to have capitalised on the lawlessness in post-Gaddafi Libya, and is believed to have preyed on thousands of would-be migrants who, like him, hail from the Horn of Africa.

Brought to an Addis Ababa courthouse for a scheduled hearing on 18 February, Kidane is said to have changed into a set of clothes, stepped out into the streets of the bustling Lideta district, and vanished. Kidane is believed to have successfully bribed his way out of custody.

On Friday, an Ethiopian court found the absconded Kidane guilty of human trafficking charges. He is expected to be sentenced in absentia in coming weeks, a sentence that could very well never be served.

“This is the way things are in Ethiopia, unfortunately,” Tekle said. “Money buys you a way out.”

With Kidane on the run, and justice deferred for his associates, survivors told MEE of the horrors they endured, while economic strife and conflict continue to foster more desperation from would-be migrants, feeding human trafficking networks across the region.

‘Every kind of atrocity’

Ethiopia still holds in custody Tewolde Goitom, another Eritrean accused of being a smuggling gang kingpin.

Tewolde, better known as “Walid”, is an associate of Kidane who also stands accused of using extreme violence in Libya, demanding ransom money from families of migrants hailing from Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia - and killing those whose families were unable to wire over sums as large as $6,000.

More than a dozen survivors of human trafficking, family members and eyewitnesses have testified against the two men during their respective trials. The collective testimony has painted a picture of the complex network of operations run by the two human traffickers spanning across Ethiopia, Sudan and Libya, taking advantage of the desperation of would-be migrants.

Some 70 percent of Ethiopia’s 110 million inhabitants are under the age of 30. Rising living costs, poverty and unemployment have left growing numbers of Ethiopians contemplating leaving the country via dangerous migrant corridors across the Middle East and North Africa, including the extremely dangerous route across Libya and the Mediterranean Sea in search for better prospects in Europe.

Such conditions are ripe for human traffickers, who have turned Ethiopia into a migration hub in recent years due to the demand for their services.

Survivors say they were lured by Kidane and Tewolde’s associates based in Ethiopia, who promised to facilitate their migration to Europe for a fee.

From Ethiopia, they were sent to Sudan’s second largest city, Omdurman. Once there, unsuspecting victims were then driven across the Libyan desert and delivered straight to Kidane’s warehouse in the town of Bani Walid, some 180 km southeast of the Libyan capital Tripoli.

The warehouse, survivors said, was where kidnapped captives were kept in squalid conditions, mistreated, and threatened with death until their families either deposited ransom money or arranged in-person meetings to hand over bundles of cash to Ethiopian-based associates of the traffickers, who would show up to such meetings with their faces concealed.

Captives were often tortured to the point of death to induce payments from loved ones, who often resorted to selling possessions and any property they might own to come up with the ransom. Released migrants would then return home, often with assistance from their embassy or United Nations agencies.

Fuad Bedru, a 24-year-old Ethiopian national, was among those caught up in the traffickers’ net. He spent over six months at the Bani Walid compound, where he recounted being tortured by Kidane himself, before his family forked over astronomical sums of money to buy back his freedom.

“Kidane lives in a home adjacent to the camp. He’d come to see us and beat someone up when he felt like it,” Fuad told MEE. “The man is a savage, a monster.

“I’ve seen every kind of atrocity. Kidane and his gang are bathed in blood. Killing is nothing for them.”

Witnesses at the trial described being bound with rope, savagely whipped, and having melted plastic poured on their bodies. Left without medical care and exposed to the elements, many migrants contracted a variety of diseases and skin infections.

“Imagine being starved, going as much as three days without eating, in addition to the suffering brought on by their brutal treatment and then being left in extreme temperatures,” Fuad said. “Only those who experienced it know what it’s really like.”

'I’ve seen every kind of atrocity. Kidane and his gang are bathed in blood'

- Fuad Bedru, human trafficking survivor

“The beatings were merciless, many people died from them,” another survivor, Etsube Mesele, 26, told MEE. “The only time you’ll go outside and get sunlight and air is when Kidane summons you for a beating."

Both Kidane and Tewolde have been accused of raping hundreds of women, Etsube confirmed.

“Walid did whatever he wanted to women. He even awarded them to other (enforcers),” he said.

Enforcers - many of them fellow Ethiopian and Eritrean nationals - assisted in meting out the brutal treatment, witnesses said.

Meanwhile, armed Libyan guards protected Kidane’s warehouses and prevented captives from escaping, meaning two of North Africa’s most notorious human smugglers could count on a makeshift militia to protect their Libyan operations bases.

Fear of reprisal

Fuad is more than just a survivor. He is also the man who spotted Kidane on the streets of Addis Ababa last year and immediately recognised his torturer.

He notified a nearby police officer, who detained Kidane and hauled him to the nearest police station.

With the human trafficker now at large, Fuad now fears for his life.

“I don’t trust anyone now. How can such a high-level criminal simply walk out of custody?” he said. “The threat to my safety is real. We [witnesses] are all at risk.”

On Friday, a court in Addis Ababa postponed the sentencing date of Tewolde’s trial, citing “procedural technicalities”.

Ethiopia’s Deputy Attorney General Fekadu Tsega stated that delays in the trial were beyond the control of the judicial system.

“Police began an investigation as soon as we detained the men,” he told MEE. “But nobody foresaw the pandemic. Covid-19 delayed the investigation and the trials, although Tewolde’s trial should conclude soon.”

But the delay in Tewolde’s case, combined with the shockingly easy escape of his dangerous colleague, have left some survivors of the human trafficking network feeling despondent.

“I have no confidence in the officials of the Ethiopian judicial system. They betrayed their own countrymen,” Etsube told MEE. “If he [Kidane] returns to Libya, you can imagine how aggressive he will be towards Ethiopians.”

A further source of frustration for victims has been the release on bail in late 2020 of Ethiopian singer-songwriter Tarekegn Mulu, an alleged associate of Kidane.

Tarekegn, once a rising star of the Ethiopian music scene, is accused of attempting to bribe the prosecution’s witnesses into recanting their testimony against the human trafficker.

The singer was first arrested in August and is accused by Ethiopian police of assisting the human trafficking kingpin with money laundering operations and receiving a wire transfer of 1 million Ethiopian birr ($24,000) slated to be used to coerce trial witnesses.

Tarekegn’s rise in the music industry was allegedly partially funded by money from Kidane’s human trafficking network, according to human rights activist Meron Estifanos, who has tracked human trafficking rings in the region for years.

“Tarekegn and Kidane have been friends for years, as Kidane loves artists and celebrities in general,” Meron told MEE.

“Kidane covered the expenses of a number of Tarekegn’s concerts in Dubai. Kidane would be sitting in the front row during performances and they’d be seen drinking and enjoying themselves together afterwards.”

For survivors of the trafficking ring, Tarekegn should be held accountable for his alleged role propping up the deadly operation.

“The singer shouldn’t be out of prison,” Tekle said. “He built his career using the blood money of innocent migrants. He knew very well what sort of activities his friend Kidane was into.”

It’s unclear what impact Kidane and Tewolde’s year-long detention has had on human trafficking networks in Ethiopia. But Meron says that the conflict in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region and general instability elsewhere in the country mean that Ethiopians will continue to be the targets of some of the most dangerous criminals in Africa.

“The war means more Ethiopians are desperate to leave,” she explained. “Traffickers are already taking advantage of the situation.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.