Andrew Tate is no role model for young Muslims - he's a vulgar misogynist

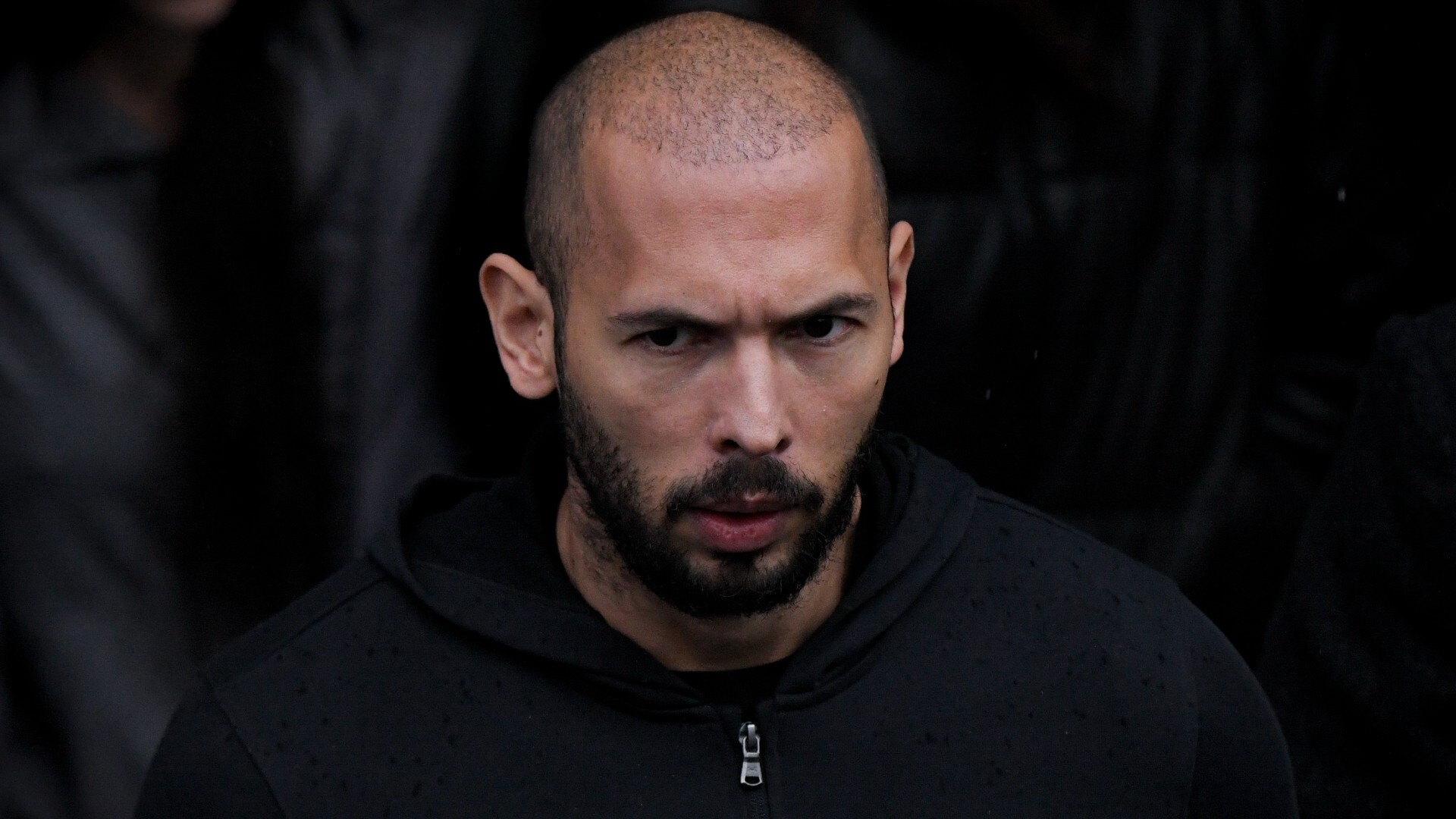

Andrew Tate, once a professional kickboxer, is now a social media influencer in the most extreme sense of the term. Midway through 2022, the British-American celebrity became the world’s most Googled man. In October, he converted to Islam, triggering an online frenzy.

On the social media platform TikTok, the hashtag Andrew Tate has more than 10 billion views. He has 4.5 million followers on Twitter and a subscription-based website, Hustler’s University, which claims to teach more than 100,000 students.

The 'Andrew Tate' model of masculinity is wildly different from the traditional masculine ideals promoted in religions such as Islam

In England, schoolteachers are raising the alarm over Tate’s influence on schoolboys. The teenage fans they worry about call him a “legend” and “Top G”. Faced with criticism of Tate, they merely ask “what colour is your Bugatti?” - quoting the man himself boasting about one of his sports cars.

Tate, a self-proclaimed misogynist, is hailed by his followers as a hugely successful businessman who promotes masculinity, hard work and self-reliance. He urges them to escape the “matrix” and take control of their lives. They see him as a role model. As Tate himself has said: “I got a big mansion, I got super cars, I can live anywhere I want, I got unlimited women … I’m an amazing role model.” He’s also very humble.

Tate was recently arrested in Romania, where prosecutors allege that he and his associates recruited young women to their webcam porn business by “misrepresenting their intention to enter into a marriage/cohabitation relationship”. Victims were subjected to “physical violence and mental coercion through intimidation, constant surveillance, control and invoking alleged debts,” prosecutors say. Tate denies the accusations.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Viral videos

What does it mean that a man who has made millions of dollars from pornography is not only extremely popular among young men in the West (especially in the country where Tate grew up, Britain), but also particularly influential among young Muslims?

Before becoming a Muslim, despite his friendship with the English anti-Islam activist Tommy Robinson, Tate had a record of praising Islam. He called it the “last religion” and argued that “no other religion has boundaries which they enforce”, noting that people “won’t disrespect Islam. Nobody will disrespect it because they’re scared.”

Viral videos of Tate speaking positively about Islam raised his profile and popularity among Muslims worldwide. One well-known American Islamic scholar even appeared on a podcast with him.

Hello @GretaThunberg

— Andrew Tate (@Cobratate) December 27, 2022

I have 33 cars.

My Bugatti has a w16 8.0L quad turbo.

My TWO Ferrari 812 competizione have 6.5L v12s.

This is just the start.

Please provide your email address so I can send a complete list of my car collection and their respective enormous emissions. pic.twitter.com/ehhOBDQyYU

Now that he has become Muslim, some of Tate’s British Muslim fans say they hope his rhetoric will change accordingly. “After accepting Islam, Tate will slowly change his ways,” one anonymous Tate supporter told Middle East Eye.

“He just converted, so he’s trying to do better, in my opinion,” said another.

So far, however, Tate’s public rhetoric has gone largely unchanged. Far from condemning his past statements and work in pornography, before his arrest Tate continued to make sexual comments about women on Twitter and to boast about his wealth and prestige.

But Tate also talks about the value of independence, resourcefulness and hard work. This resonates with people. One 20-year-old Muslim woman who is critical of Tate but likes elements of his message joined Hustler’s University to see what it was about. “A lot of his fan base benefit from his content and tangibly improve their lives,” she told MEE. “Even though his message isn’t necessarily revolutionary or groundbreaking, it’s connecting with people who have benefited from it.”

Personal charisma

Tate’s popularity is partially due to his personal charisma, and the sense that he’s authentic and practices what he preaches. “Everything he says, he does. He’s got the life - he worked hard for it,” a 19-year-old Muslim fan told MEE. “He says everything in the simplest way possible, something that not everyone can do.”

And Tate fills a vacuum: many young men, and not just Muslims, feel that there are few compelling figures online who promote masculine virtues and encourage material success. They see Tate as standing up to the left-wing, progressive discourse common on apps such as TikTok. He’s anti-establishment, they feel - schoolteachers hate him, giant social media companies ban him from their platforms, and he’s viewed as a rare voice offering young men solutions to modern woes.

But Tate made millions from pornography, and many of his popular videos feature explicitly misogynistic language. The fundamental contradiction in his brand is that the “Andrew Tate” model of masculinity is wildly different from the traditional masculine ideals promoted in religions such as Islam, to which Tate converted.

This was pointed out recently by prominent writer Nassim Nicholas Taleb, himself a Christian: “Traditionally men expressed their ‘strength’ by being gentle, gracious & protective … The Andrew Tate problem is that both young men and ultra-feminists will now associate the expression of ‘masculinity’ with his style and psychopathy in general, not with the traditional forms,” he tweeted.

Writer Louise Perry similarly argues that the “masculine role [Tate] craves is a strangely modern one, since it cuts away so much of what constitutes historic manhood … Tate’s pick ’n’ mix gender narcissism is all about rights - to dominance, strength, and ‘bitches’ - without any of the duties to family and community.”

Shallow discourse

Many Muslims criticise his rhetoric, too. Speaking in relation to Tate’s conversion to Islam, prominent American Islamic scholar Yasir Qadhi said last November: “As for macho-speech, putting women down, mocking them, making them feel bad - where did you learn this masculinity from? Where in the Quran and sunnah [prophetic tradition]? Where in the sirah [biography] of the Prophet, peace be upon him, did you learn this to be masculinity?”

He went on: “So, if any convert embraces Islam, we welcome them … but if we want to put them on a pedestal or platform, they had better get their act together. They had better learn to speak properly about the din [religion] if we want to promote them.”

Tate's rhetoric … drowns out any serious discussion about problems with the prevailing political and economic order

More than anything, Tate’s high profile demonstrates the shallowness of public discourse, especially on social media. Tate’s followers say he teaches the truth about the world. But his emphasis on wealth, glamour and luxury cars means that his rhetoric is materialistic, individualistic and extraordinarily superficial.

For example, it’s unclear what the “matrix” that Tate speaks about, which supposedly suppresses us and keeps us trapped, actually is - besides a vague but dramatic-sounding conspiracy theory. Tate’s rhetoric might sound radical and profound, but it drowns out any serious discussion about problems with the prevailing political and economic order and how to fix them.

Many young Muslims (and young people more generally) are deeply discontented with the modern world. They need ethical guidance, strong role models and a sense of meaning. Instead, from Tate they get Hustler’s University, “Top G merch” and a heavy dose of vulgar misogyny. This is unlikely to do the trick.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.