Where the abused are abused: Welcome to Saudi Arabia's shelters for women and girls

First, there is darkness and only the sound of traffic. Then a fluorescent light flickers to reveal the inside of an abandoned security guard’s hut down the street from a luxury mall, Aisha Alnijbany’s home for the past four days.

“I want to ask followers a question,” she says, peering at the screen. "A girl's family abandons her at an orphanage, a women's shelter, wherever. When you leave, is it right for them to expect you to go back to your family? Or does the full responsibility still remain with this government facility?"

Since the start of the year, Aisha, 22, has vlogged from the streets of Riyadh, telling her story and documenting her homelessness over more than 13 hours of footage on Instagram.

At age three, she says, her father left her at a state-run shelter where she spent the next 17 years. When she spoke out about conditions at the shelter, posting photos of locks and chains, using hashtags to draw attention to her case and saying she was imprisoned, she was sent to prison for a year and a half. And then, she was slapped with a 10-year travel ban and released onto the street.

“Are you doing this to me because I demanded my freedom and my rights?” she says.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Her videos have stirred discussion and support among Saudi female activists and observers who say they’ve never seen anything like this - a homeless Saudi woman publicising her own case. She is also perhaps the ultimate example of how the shelters, which are meant to protect the kingdom’s most vulnerable women and girls, are failing.

“These are prisons,” said Saudi activist and journalist Khulud al-Harithi in a Twitter space organised by London-based advocacy group ALQST in April, in which Aisha’s case and others were raised. “It’s as if they punish you because you’ve been abused and you don’t have a family. They don’t deserve to be called shelters.”

'A climate of fear and repression'

There are a variety of reasons a woman or a girl might end up in a state-run shelter in Saudi Arabia. They could be fleeing domestic violence. They may be suspected of committing a crime and be awaiting charges.

But they might also have "disobeyed" their male guardians or tried to run away from home or, like Aisha, be abandoned, said Rothna Begum, women’s rights researcher for the Middle East and North Africa for Human Rights Watch.

“It could be that they protested or they defied the driving ban so they can end up spending some time there,” she said. “It could be that the families have dumped them at a police station and don't want anything to do with them and the police will take them there.”

Once inside, they are locked up until a male guardian, often the same person abusing them, agrees that they can leave; or until a woman agrees to marry and has a new guardian.

Alongside the headline-grabbing reforms for women in Saudi Arabia in the past few years, the shelters where girls and women have committed suicide, rioted for better conditions, attempted escape and been killed by relatives soon after their release, continue to operate without any reforms, say Saudi activists, human rights researchers and women who have stayed in the shelters.

Not only are these state-run shelters still operating, without change, as Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman’s modernising project unfolds, but the situation for the kingdom’s most vulnerable women, they say, is significantly worse in the wake of the high-profile arrest of women’s rights activists in 2018.

Several of the arrested activists were among those who raised a popular petition with King Abdullah in 2014, asking, among other requests, for women to access shelters whenever they needed without having to be investigated by the state and to be able to leave whenever they wanted as well, without having to be in the custody of a male relative.

Unsuccessful in that pursuit, they worked on setting up a nonprofit alternative to the state-run shelters that was to be called Aminah, “safe” in Arabic. They had secured land with the help of a philanthropist, and officials with the Ministry of Social Affairs told organisers they were about to approve their application. Two months later, the activists were arrested.

One of the charges filed against the activists was that they tried to establish an association - which is unnamed - against Saudi regulations. Waleed al-Hathloul, the brother of Loujain al-Hathloul, who was among those picked up, wrote that he believed his sister’s work on Aminah “was one of the main reasons” she was arrested.

For Saudi girls and women trying to flee abuse, the impact of the arrests wasn’t just that Aminah was shelved, activists told MEE. A network of powerful Saudi women who used their positions and wealth to quietly support girls and women stuck between abusers and abusive shelters abruptly stopped offering help as well. And officials in state agencies who had once helped women off the books were summoned for questioning.

“This climate of fear and repression, it killed the urgency of seeking help for those survivors of violence or women being treated unfairly by the legal system,” said Hala Dosari, a prominent Saudi activist and scholar, and one of Aminah’s organisers.

“You can't imagine how disheartened I am when I receive those emails that I used to receive before. I used to refer them to good sources for support. Now there is none, but I get all those emails the same.”

The implicit message to girls and women trying to escape abuse in their homes was to stay quiet. “They are not able to speak up. If you speak up, it’s not about your case any more. It’s about the image of a country. They might treat you exactly like an activist.”

Shelter life

There are several types of state-run shelters in Saudi Arabia, including Dar al-Reaya (The House of Care), a collection of facilities across the kingdom which holds girls and women between the ages of 7 and 30 - and where Aisha was for 17 years.

According to the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development, which runs Dar al-Reaya, there are only two types of girls and women who turn up at the shelter. There are Saudi girls “who have suffered from bad social and psychological circumstances that force them to stumble and deviate from the straight path” who require “good care, social correction and strengthening of religious faith”. And then there are delinquents.

Both types are to be set back on “the right path”, says the ministry. “If the girl becomes good, the family will be good, and accordingly the society.”

But activists and researchers who have spoken for years to former detainees say the facilities are not the safe havens or places of rehabilitation that the state paints them to be, but instead are lock-ups rife with abuse.

When you arrive, your phone is removed and there are instances of women and girls being strip-searched and even put into solitary confinement before entering the main ward.

According to an ALQST report released last year, women reported that they had been deprived of recreational activities and were unable to continue their studies inside Dar al-Reaya. They also described harsh punishments, including being made to stand for six hours at a time.

The situation is particularly grim for victims of domestic violence. Rather than provide protection, activists and researchers say girls and women trying to escape abuse at home are encouraged to reconcile with their guardians or families and can have their detentions prolonged if they resist.

One woman held inside Dar al-Reaya told Begum that in the facility where she was held, girls and women detained for longer than a month who were resisting reconciliation could be given punishments, including regular floggings and solitary confinement, until they agreed to concede.

Similar punishments, the woman told Begum, were also meted out to detainees deemed to have committed a violation within the shelter, including failing to read the Koran daily or engaging in a sexual relationship with a fellow detainee.

A former inmate who was in Dar al-Reaya after her family filed a case against her for being absent when, in fact, she says she was reporting abuse, told Raseef22 that solitary confinement in the facility where she stayed was “a mattress in the middle of a bathroom” and that cameras were installed everywhere, even in the toilets.

If a male relative isn’t available or doesn’t agree to sign off on a woman or girl’s release within a couple of months or after a woman turns 30, they are transferred to a Dar al-Theyafa, another type of state-run shelter where they can end up for much longer periods - and may never leave.

“One woman described it as being worse than Dar al-Reaya - which is quite hard to imagine, because when you are hearing about floggings and solitary confinement, how could it be worse?” Begum said. “But what I had heard was that Dar al-Theyafa was more depressing, and that was because it was women there for months and years, really long periods of time.”

As at Dar al-Reaya, the women - who may also have children with them - are restricted from leaving the facility and can only leave if their guardian agrees, or if they marry, which shelter workers frequently coerce the women to do, said Dosari.

“The officials and the social services think of this as making sure that the women are in a safe environment rather than being on her own,” she said.

The men who typically come forward seeking to marry women in the shelter find it challenging to marry in more straightforward circumstances, Begum said. They may be convicted criminals who have been in prison. Or they might be in search of a second or third wife.

Given the precarious situation of the women, said Begum, the men see them as an easier catch: “‘Well, I'm saving her from a life of being imprisoned. So she would be more willing to marry me’,” she said.

It is not surprising that some women choose to return to their homes and or the abusers who sent them fleeing in the first place, said Dosari. “It’s a very weak system. That’s why most of the women are in a loop, basically. They cannot really get out of it,” she said.

Deterrent force

Looking at the numbers alone, the percentage of Saudi girls and women held in state-run care facilities is very small. In 2016, the last time publicly available figures were released, 233 girls and women - out of a population of then over 13 million female Saudis - were held in seven facilities across the kingdom.

Two years later, a Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development official told Saudi news site Al Madina that another five would be rented, in part to provide space to detain women, now driving legally, when they broke traffic laws.

It is unclear whether the kingdom followed through on this plan, how many facilities are operating now and how many girls and women are currently detained in them. Data has not been released since 2016 and Saudi Arabia did not respond to MEE’s request for comment for this story.

What the numbers fail to capture about the care homes, Saudi women told Middle East Eye, is the sheer power of their existence as a deterrent force in a kingdom that continues to be governed by discriminatory and repressive guardianship rules.

'The girls going in there are the ones that are really beat up and abused. If they get out, they will have no means of talking to anyone'

- Thoraya, Saudi woman

To flee or to speak out about one’s abuse in the first place is very rare in Saudi society.

“People won’t be like, ‘Oh, she left her house because her dad is abusing her. Shame on him.’ It will be like, ‘Look at that girl. She went. She left the house because she wanted to live an open life. She will be blamed for stuff that she never thought of,” said Thoraya, a Saudi woman who spoke under a pseudonym because she feared repercussions from the government for speaking publicly.

“You are the disobedient child. You are the disobedient wife. You are the woman. You should compromise. You should listen. You should lower your standards. You should give in more. You should be more forgiving.”

Thoraya said her father, who was well-educated and had a professional career, once threatened to send her to Dar al-Reaya. “I remember he said, ‘You marry this guy or I’m going to send you to that place’,” she said.

So the homes serve as a looming threat that keeps girls and women from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds and geographic locations in check under their guardians. Those who end up in them are truly desperate.

“Usually, the girls that are in those positions will never, ever have a voice to speak out. The girls going in there are the ones that are really beat up and abused. If they get out, they will have no means of talking to anyone,” Thoraya said.

Fleeing for freedom

The shelters are just one piece of the kingdom’s guardianship system, a decades-old collection of laws, policies and practices which, like most Gulf countries, require women to get permission from a male guardian for a wide range of activities during their lifetime.

But they are a particularly important piece because they help maintain the system, enabling domestic abuse through their ineffective intervention, Begum said. “The authorities will enforce the male guardianship system by forcing women back into families or to new guardians, but always to keep them in that space,” she said.

The stark choice facing Saudi women and girls is reflected in a significant increase in those fleeing the kingdom in recent years, including in 2019, dubbed the year of the runaway, when several Saudi women broadcast their escapes publicly on social media in an effort to get to safety.

That January, Rahaf Mohammed barricaded herself in a Thai airport hotel room to avoid being taken back home before she was given refuge in Canada. Then in April, sisters Wafa and Maha al-Subaie pleaded for help from Georgia, where they had fled. In June, Dua and Dalal al-Showaiki asked followers to give them a hand after they escaped their family during a holiday in Turkey.

Of course, Saudis have always lived abroad, but what is different now is that so many that are leaving are seeking asylum. “To seek asylum, it means you’re desperate,” Dosari said. “This is something that never happened in Saudi.”

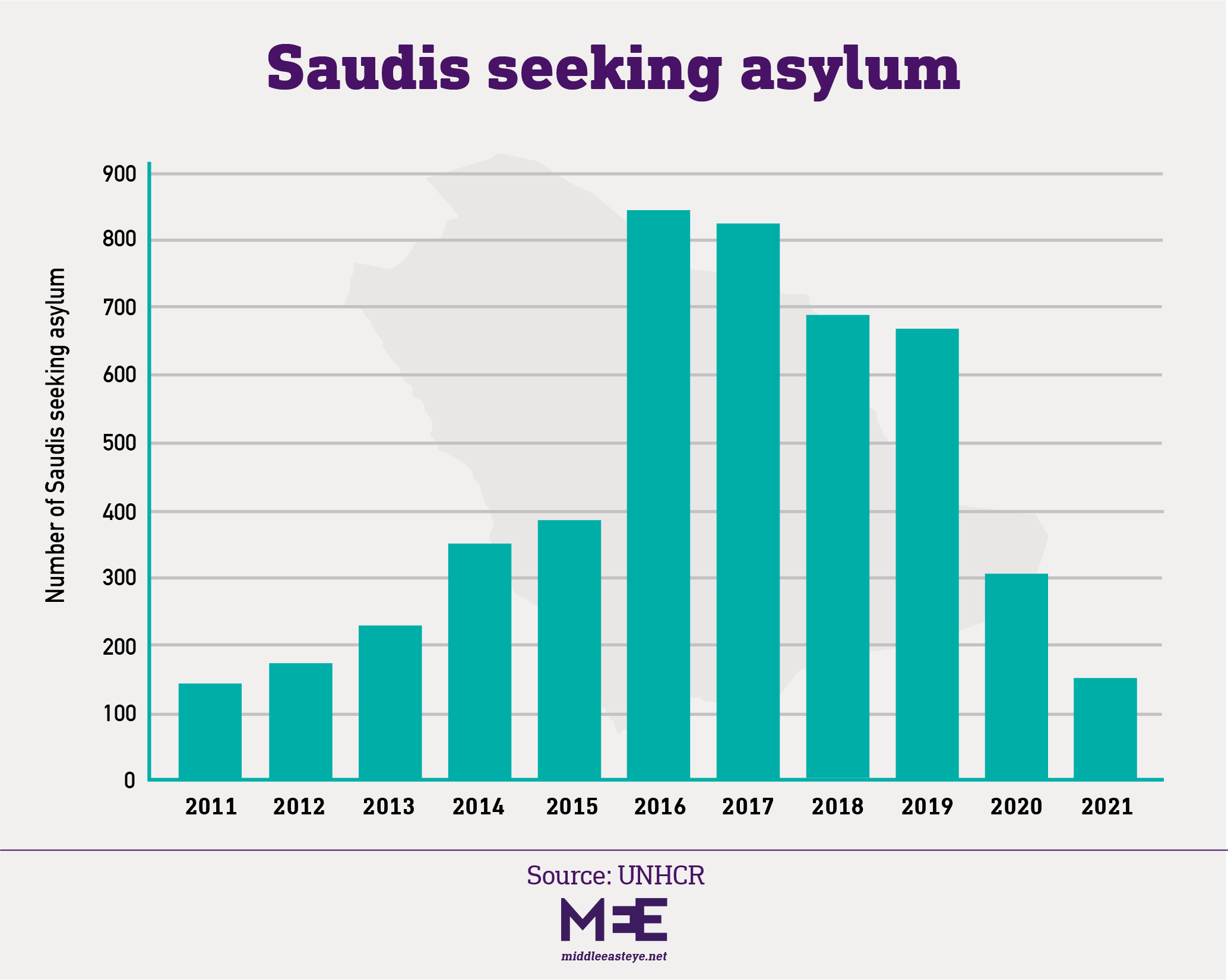

According to UN figures, the number of Saudis seeking asylum rose significantly in 2015, the year King Salman came to power. That year, 395 Saudis fled the country, but every year since - with the exception of 2020 and 2021 during the Covid pandemic - that figure has stayed consistently high.

“It’s a sad thing that we, as Saudi women, the first step we take to protect ourselves is to run away from our country and lose our citizenship,” said Saudi activist and journalist Khulud al-Harithi. “We are from a country where there are no wars or crises that could force a woman to seek asylum. So why do we have to lose our citizenship? What does the government stand by one citizen to the detriment of another just because she’s a woman?”

Dosari is often asked to write expert letters for asylum seekers, requests which have also jumped significantly. “I’m getting more and more of that,” she said. And asylum for Saudi women and girls, despite the clear continued impact of guardianship rules, is not guaranteed.

Bethany al-Hadairi, Saudi case manager at The Freedom Initiative and senior fellow on human trafficking at Human Rights Foundation, which are both in the US, said she knows of several recent Saudi asylum cases in which those applying have struggled to convince judges that returning to the kingdom would be dangerous.

The US, she said, already has one of the worst approval rates for Saudi asylum cases, but it has become even harder, particularly for women.

“I know of a couple of cases - people on their maybe second or third appeal at this point - who are just terrified to return but almost giving up,” said Hadairi. “It’s difficult to explain to a judge in the United States who expects a legal system to be straightforward and as it seems and as it is written. It’s just not the case on the ground [in Saudi].”

It’s been a struggle for Saudis to protect themselves from being returned to dangerous situations as a result of the Saudi public relations drive put in place following the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, campaigns that "have real damages on the ground in Saudi as well as here for families that are trying to get protection in the US for asylum".

And this, said Dosari, is the power and the impact of silencing the most vulnerable women and girls in the kingdom, who are locked in care homes, while the government is promoting the stories of women who attend concerts, drive cars and hold down jobs.

“There is no counternarrative that really tells you the truth. People aren’t willing to take the risk,” she said. “And it is a risk.”

Perhaps no one knows this better than Aisha Alnijbany who, even now, roams the streets of Riyadh, still speaking out and looking for refuge.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.