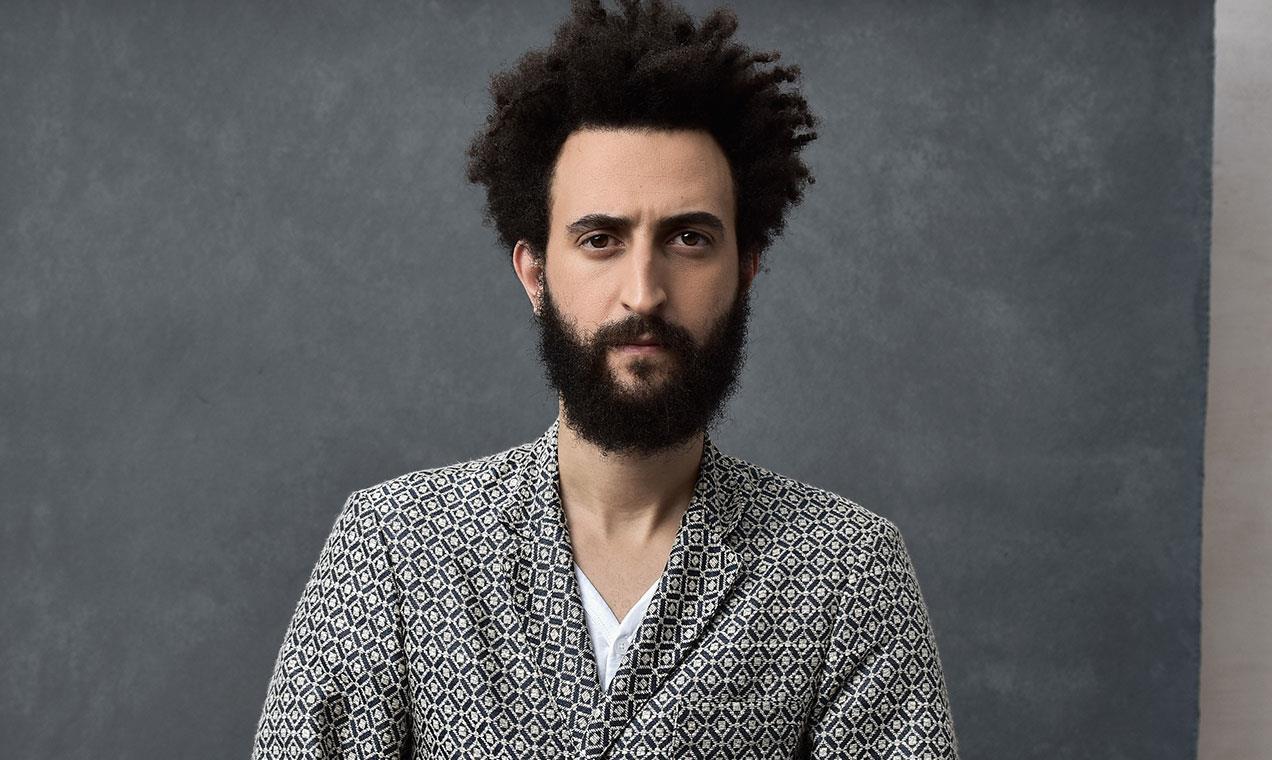

The Unknown Saint: Robbers, riches and religion make for fresh film debut

Alaa Eddine Aljem’s debut feature The Unknown Saint has come out out of nowhere to inject Arab cinema with a breath of fresh air.

It’s that rarest of beasts: a smart, side-splitting Arab comedy tackling collective faith, the presiding craving for a saviour and the primal necessity of finding meaning, or rather conjuring up one.

The underlying sentiment is simple, as Aljem explains: “We, as a nation, need something to believe in. We cannot be just individuals. We need something to unite us; something to push us collectively to go forward…even if it’s fake.”

The resulting feature juggles remarkable skill, humour and pathos, big ideas and highly entertaining set-ups, marking this Moroccan feature, which had its world premiere at Critics’ Week in Cannes, as the most original Arab debut of the year.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Arab comedies do not have a strong - or any, for that matter - track record at Cannes, an event that has often fetishised the poverty, violence and oppression of a region that is not as homogenous or streamlined as its films sometimes make it out to be. The Unknown Saint is an anomaly in that too-predictable Arab narrative.

Robber, money, problem

It all begins with a car chase. Amine (Younes Bouab, the eternally frowning scruffy-haired anti-hero of Zero and Razia) is being chased by the police moments after stealing a stash of money. Unable to flee from the looming entrapment, he hurriedly hides his bounty in a deserted village.

After he’s released from prison, the thief returns to the village, only to find that the shrine of an "Unknown Saint" has been erected over the spot where he hid his cash. Meanwhile the surrounding wasteland has blossomed into a sizeable community built around the mausoleum of this mysterious holy man.

To retrieve the loot, Amine enlists the help of his former partner, The Brain, a dim-witted conman whose ill-fated antics constantly derail the pair’s venture. Amine’s fate is also entangled with two different men: Kamal (Anas El Baz), a young doctor arriving in town to take charge of a dispensary that doesn’t need him; and Hassan (Bouchaib Semmak), a resident of the nearby dying village which is deserted after its people left and regrouped themselves around the new shrine.

All three characters are waiting for things that never happen: the doctor for real patients instead of the elderly women who use the dispensary as a place to hang out; Hassan and his father, for the rain which would save their dying land; and Amine for the increasingly elusive opportunity to get back his money.

Delusion is the de facto mode of life in this village, from the shrine of an imaginary saint without miracles, to the standard tablets that the doctors robotically hands out to every patients for every sickness. It is also a vision of a stagnant Morocco stuck in a standstill, a theme echoed in nearly every frame of the film.

Inspiration? Keaton, Tati, Ozu

Born in Rabat in 1988, Aljem earned his BA in film directing from the School of Visual Arts in Marrakech and later an MFA from the INSAS school in Brussels. His first four short films nearly all contained a comedic element, something that find its full expression in his full-length feature.

He garnered attention with his fifth short, The Desert Fish, a family drama about a grave-digger father who is reluctant to allow his son to peruse his dream of becoming a fisherman and leaving the land.

Largely different in tone and style from The Unknown Saint, The Desert Fish still displayed Aljem’s talent in evoking sparse landscape with meticulous exactness and generous emotionality. Echoes of the father-son relationship can also be traced in Hassan’s sympathetic connection to his father.

The genesis of Saint originated in the extensive trips Aljem used to embark on with his mother when he was a kid. “I used to notice these white shrines stranded in the vast desert, in the middle of nowhere,” he recalls. “I always found something cinematic in that.

“Many years later, while scouting for The Desert Fish, I stumbled upon one of them again. The shrine was solely surprised by an elderly guardian. I asked him which saint does this mausoleum belongs to, but he didn’t know. He was dead serious, which I found absurd. This is how it all started.”

The absurdity of the world stemming from the shrine is perfectly captured in Aljem restrained, deadpan comedic style. Inspired by Buster Keaton (in the forlorn stone faces of the characters), Jacques Tati, and by extension, Elia Suleiman, the pared-down visual structure is augmented by still tableaux where action is always contained (note: all 820 shots of the film have been storyboarded in pictures in pre-production, a testament to Aljem’s fastidiousness).

Unlike Suleiman, movement in Saint often occurs vertically rather than horizontally, allowing for more comedic possibilities and lending the film more dynamism.

This lack of camera movement is an aesthetic which Aljem developed throughout his shorts for two reasons: to sustain continuity inside the frame; and to arrive at a basic visual language.

Mostly he prefers wide-angled frames, with medium shots only intermittent and close-ups completely absent. Like the works of Tati and Suleiman, this gives the eyes of the audience the freedom to roam in any direction; unlike the other two, Aljem’s compositions are far less cluttered.

Aljem also cities the great Japanese master of family dramas, Yasujiro Ozu, as a major influence on his visual identity.

“I love how everything is so precise in Ozu’s tableaux, how actors have the freedom to move from side of the frame to the opposite one. I love how everything is so frontal in there,” Aljem says.

“As time went by, I found a harmony between my writing, that mixes comedy and drama, and this type of aesthetic. It also helped me to recognize the importance of the mise-en-scene in the narrative, the staging. The positions of the camera, the homogeneity of the staging, also reveals a lot within the narrative, as well immersing the viewer within the general atmosphere of the film.”

That pared-down visual style also extends to the characters, who defy commonplace characterisation. No one here has a backstory. No one is psychologically rounded. Rather there’s something elementary about Aljem’s characters – almost intentionally archetypal - which helps quicken the pace of the story.

The comedy is thus driven not from how the characters are, but rather from the deliciously incongruous situations they are thrust into, contrasting the realistic backdrop and the ridiculousness of the narrative.

Conjuring politics and religion

Aljem insists that the film is not anti-faith, that he wanted to be as respectful and not offensive as possible.

“We’re laughing with the characters, at the situations they’re in, and not their faith, and surely not at them. We’re not making fun of anyone,” he says.

And yet, the overriding sentiment of Saint is clearly anti-organised religion – and convincingly so. The Marxist maxim of religion as the opium of the masses is literally manifested in various strands of the story: from the village’s blind belief in the anonymous saint and the idle wait for the rain miracle, to the commodification of faith into an exotic touristic hotspot and the senseless rituals performed without a persuasive rationale.

At the same time, Aljem doesn’t entirely dismiss the possibility of high powers, permitting different interpretations for happenings that could be perceived as divine intervention, or simple coincidences.

There’s also the political dimension of religion: a tool passed on by the powers that be not always to distract from the real problems at hand, but to forge a collective goal for the masses to get behind.

Aljem explains how Moroccan society sometimes uses popular beliefs to bind it together – and how some of these are more absurd than those in the film, including the belief that Mohammed V had walked on the Moon.

The arrival of the then young monarch Mohammed VI in 1999, he says, brought new energy and hope, moving Morocco to modernity and constructing a new nation from the ashes from Hassan II’s oppressive reign; but it ultimately proved to be impermeant. “Now I think, we’re reaching the end of this hope. We now need a new energy; a new objective. Many of my friends were hoping that Morocco would win the World Cup bid, not because they care about football, but because they see the need for a new national project,” he adds.

“We needed the hope associated with the World Cup lie; we needed to hear on TV that the government will build new roads and hospitals. Same goes with the film’s saint. We know it’s fake, and yet perhaps it’s instrumental to give people something to collectively get behind, even for a short period.”

Poverty of imagination

Despite being tipped as one of the hottest tickets at Cannes this year, the funding of Saint was not something Aljem takes for granted: the success of The Desert Fish was irrelevent to the producers who initially deemed his follow-up project as too crazy.

“Producers told me that being an Arab film-maker, I should not start my feature filmmaking career with a comedy. Since it’s my first film, they asked me to stick to a ‘well-identified’ theme so that could travel internationally. They wanted it to be about terrorism, women’s conditions, poverty or immigration.

'Being Arab doesn’t make me no less human than you are'

- Alaa Eddine Aljem

“Being Arab doesn’t make me no less human than you are. We have as diverse subjects and interests and concerns as the rest of the world. If someone wants to tackle poverty because they have an urge to say something about it, they can certainly. But I’m not going to do it for the sheer sake of going internationally.”

Eventually, Aljem managed to attract major French distributor, Condor and German sales company, The Match Factory, who both signed up the film on the basis of the script - the same script that was deemed unsellable by previous producers and agents.

“It was the sweetest revenge,” Aljem says. “What attracted Condor and The Match Factory is exactly what deterred the others: the fact that it’s different from the things you usually see from the Arab world.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.