The forgotten history of Jerusalem's Palace Hotel

Last month, US President Joe Biden met Israeli Prime Minister Yair Lapid at the Waldorf Astoria luxury hotel outside the Old City of Jerusalem. In preparation for Biden’s arrival, the building and the streets leading to it were crowded with Israeli and American flags.

When asked what was discussed in their meeting, Biden frivolously remarked: “American baseball". The remark was not entirely misplaced: the two states have treated the Middle East as their playing field for decades.

Despite its deliberate obliteration, the Palace Hotel's architecture continues to bear witness to its obscured past

I visited the building a few days after Biden’s visit, and the flags were still up. But it was clear that I was not merely looking at a luxury hotel. Years of exposure to archival documents and historical photographs of the site flashed through my mind. I was looking not only at the present but also at a forgotten - or more accurately, erased - period of history.

The story of the building goes back to the 1920s, when Hajj Amin al-Husseini, a leading Palestinian figure and head of the Supreme Muslim Council, decided to undertake major architectural projects in Jerusalem.

The council’s main focus was the renovation of Al-Aqsa Mosque complex. But it also undertook another major project in Jerusalem: the construction of the Palace Hotel outside the Old City.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The Palace Hotel was not a mere architectural undertaking. British colonial rule in Palestine was still in its early stages, and Husseini understood that his authority and credibility as the main Palestinian leader necessitated tangible steps towards the enhancement of the Palestinian presence in the city - especially given the growing Zionist and British colonial investments in Jerusalem and its vicinity.

The hotel project would also have offered the council a source of income outside the restrictions of British colonial authorities.

Competing with colonialism

Upon its completion in 1929, the Palace was one of the most luxurious hotels in Jerusalem, with a stately entrance hall, marble accents, modern guest rooms, and private telephones. The project was a testament to the Supreme Muslim Council’s desire to showcase that Palestinians could compete with their colonial counterparts, a stance that was accentuated with the construction of the rival King David Hotel in its vicinity in 1931.

guidebook, 1934 (Designed by Jamal Badran)

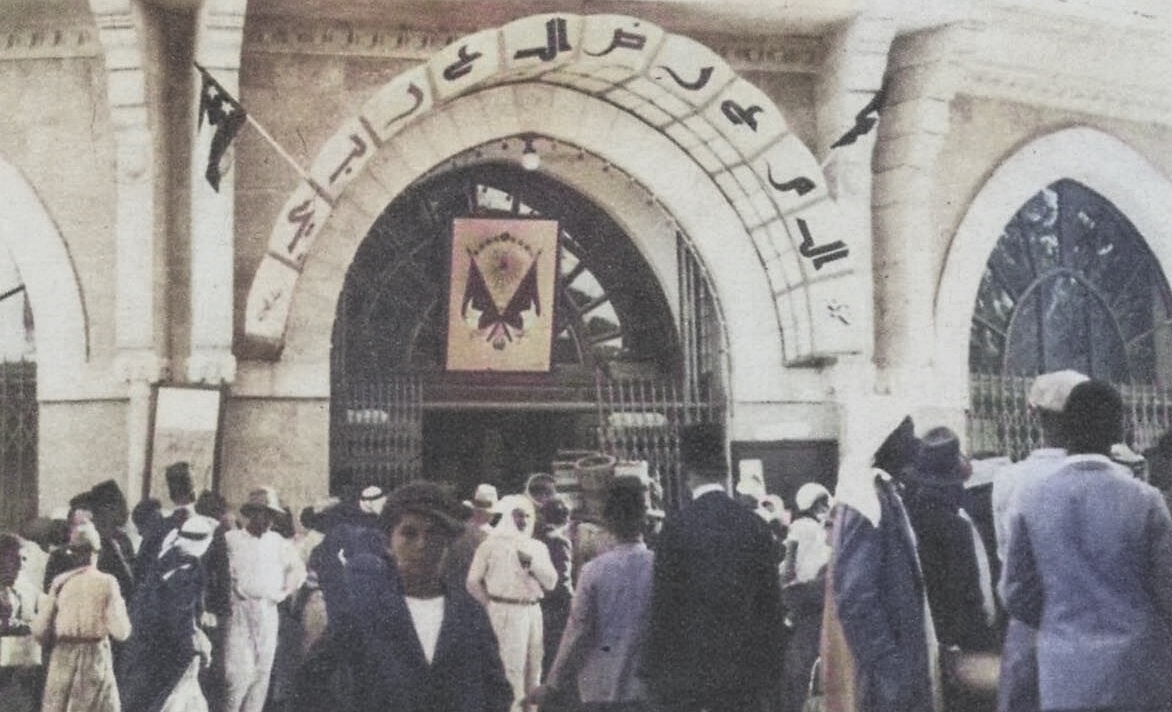

Two events comprised the most meaningful expressions of the Palace Hotel’s role in asserting Arab Palestinian identity during the British Mandate years: the 1933 and 1934 Arab Exhibitions in Jerusalem. The exhibitions, hosted at the hotel, were profoundly significant to the histories of modern Palestine and the broader Arab world, reinstating their historical bond after the region’s geopolitical division following World War One.

The exhibitions showcased the industries, crafts, and artworks of participants from across the Arab world. Visitors could stumble upon Nabulsi soap next to Damascene textiles, or perfumes from Tripoli. The Palace Hotel’s halls and corridors were adorned with textures, smells, and objects that knotted the region’s diverse creations into a single continuous thread.

The exhibitions offered a new space of endless possibilities. They showed that Arab progress was possible despite, and not because of, European colonialism.

Materials from the two exhibitions - including stamps, postcards, medals, and participation certificates - are living testaments to the spirit of Arab unity that underpinned them. They were designed by Jamal Badran, a renowned Palestinian artist who drew borderless maps of the Arab region, with lines radiating from Jerusalem to the Hijaz and the Maghreb. His drawings revealed geography not as it was, but as it ought to be.

Arab renaissance

The two exhibitions were public events in every sense of the word. They received extensive coverage in local and regional Arabic media, which both echoed and helped to articulate their ethos. The events were seen as evidence of an Arab cultural and economic renaissance.

But the Palace Hotel’s fate did not mirror the enthusiasm that the two exhibitions cultivated. In 1935, just a year after the second one was held, the hotel had to cease operations for financial reasons. Competition with the King David Hotel had grown increasingly fierce, and the turbulent political climate did not help.

The Supreme Muslim Council subsequently leased the Palace Hotel to the British administration, ushering in a new era of colonial takeover. After the Nakba of 1948, the building was confiscated by the Israeli state, which used it to house the trade ministry. In 2008, it was announced that the site would reopen as a hotel - this time, the Waldorf Astoria.

After a massive renovation project, the Waldorf Astoria opened its doors to visitors in 2014. But this was a “renovation” in name only. The Palace Hotel was entirely hollowed out, with the exception of its original internal staircase and exterior facade, while its pillars, tiles, lamps, glasses, plates, and artworks were looted, with some eventually making their way into Israeli auction markets.

Despite its deliberate obliteration, the Palace Hotel’s architecture continues to bear witness to its obscured past. As I approached the building, I looked at its original facade, where a stone plaque remains in place.

On it, words are inscribed in Arabic: “just as our forefathers built and did, we build, and we do. This lodge was built by the Supreme Muslim Council in 1929.”

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.