How Yemen’s Marib became the frontier for Roman expansionism

When Wendell Phillips encountered the tribes of Marib in Yemen, it didn’t turn out so well for the acclaimed American archaeologist turned oil magnate, then aged 30.

“The one big problem that confronted me was to get everyone connected with the expedition out of Yemen alive and safe,” he later recounted in his memoir, Qataban and Sheba: Exploring the Ancient Kingdoms on the Biblical Spice Routes of Arabia (1955).

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

In this book, Phillips retraced his misadventures, which included his kidnapping and fortuitous release during the Imamate period. Though not explicitly conceding wrongdoings in his memoir, it’s quite likely that his self-assured bravado had ruffled a few feathers locally, considering the long-established customs in use to seek passage for goods and people, permissions and protection.

Once King Ahmad bin Yahya, the penultimate ruler of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen, cut off his supplies and mistrust grew between the American and local people, he had to leave.

The kingdom was the successor state of the Zaidi imamate, which broke off from the Ottoman Empire in the late 16th century, and subsequently became the main power in northern Yemen.

Phillips had mounted an ambitious scientific expedition to survey Yemen’s ancient sites, following in the footsteps of the Egyptian archaeologist Ahmed Fakhry before him. Their research led them to Marib in pursuit of the legendary Queen of Sheba (Bilqis in Arabic), a ruler referenced in biblical and Islamic traditions.

A number of scholars had come to believe that the ancient land of Sheba, mentioned in the Bible and the Quran, was to be found in Marib.

The American and his team excavated around the temple known as “the sanctuary of Bilqis” (Mahram Bilqis or Awam Temple), on the outskirts of Marib city, an area not far from the frontline of Yemen’s latest war of attrition, which pits Houthis against pro-government forces.

The Phillips episode is one of many reinforcing the stereotypical view of Yemen as an unruly place. Scholar Nadwa al-Dawsari, non-resident fellow at the Middle East Institute, says that the honour-based codes of tribes in Yemen are largely misunderstood by external observers and analysts. “Tribes are eager to see the war end and to restore peace and stability to their areas,” she writes.

Rich history

Rich in oil and gas, Marib is a cherished, lucrative prize. It hosts oil fields, a refinery, gas reserves and a pipeline that supplies the entire country. It is also a government stronghold and has a responsive local administration.

Until the recent Houthi offensive, Marib had often been seen as a rare island of peace and relative prosperity in the midst of a country that has for six years been torn apart by war.

As archaeologists and Yemenis know, the name of Marib echoes further across the chambers of history. In ancient, pre-Islamic times, Marib had already developed a rich culture and attracted the attention of other empires as the former capital of the Sabaeans.

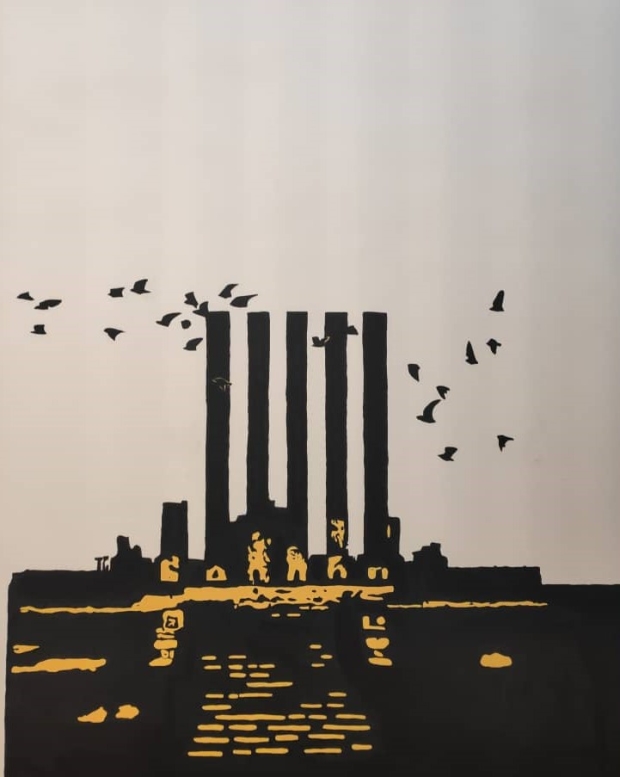

The Sabaeans were a distinct Semitic people who predated Arabs in the region. Their kingdom flourished for over a thousand years from around 800 BCE. A number of extant sites attest to this, such as the nearby Awam temple and the iconic six remaining pillars from the Barran temple enclosure, which have withstood over 2,700 years of glorious and at times turbulent history.

Together, the two temples were dedicated to the pre-Islamic moon divinity, Almaqah. Almaqah was the male moon god who also borrowed attributes from the traditional sun goddess, a primordial mother figure. Worshippers prayed for rain and looked for answers in oracles. Marib has fascinated trespassers ever since, most notably the Romans.

‘Happy Arabia’

When Aelius Gallus, Roman prefect of Egypt, set his eyes on the land we now identify as Yemen, he imagined glory, triumph and significant career advancement.

For the Romans, Yemen was at the southern and most unexplored tip of ancient Arabia, which comprised three geographical areas: Arabia Deserta (roughly corresponding to the north-northeastern part of Saudi Arabia), the Roman province of Arabia Petraea (with Petra as the capital city of the Nabateans), and Arabia Felix - “Happy Arabia”, the latter encompassing today’s Yemen.

In 31 BCE, Julius Caesar's great-nephew Octavian defeated Marc Antony and Queen Cleopatra’s fleet at the Battle of Actium.

With these last rivals out of the way, the victory strengthened Octavian’s claims to his great uncle's mantle and the Roman republic approached its final days. A few years later, in 25 BCE, a confident and expansionist Octavian, who became Emperor Augustus in 27 BCE, ordered his prefect of Egypt, Aelius Gallus, to gather troops and plan for a military excursion into southern Arabia.

The Romans had wanted to control the spice routes since southern Arabia was known for its frankincense, myrrh, cinnamon and other precious commodities, essential for myriad pagan ceremonies and sacrifices. The expedition may also have been to advantageously position Rome in an early competition over territory and resources with the Parthians in southern Arabia.

According to the Greek historian and geographer Strabo, Augustus “conceived the purpose of winning the Arabians over to himself or of subjugating them”. If persuasion of Roman greatness wouldn’t work, then force surely would, Strabo, a friend of Aelius Gallus, tells us. Rome was, by then, an empire in all but name.

Under the command of Gallus, Roman and Egyptian troops cemented alliances with the Nabateans and Judeans. Together, they set off for the desert lands of Arabia with a 10,000-strong army.

It took them six months to reach the area of Al Jawf, in modern-day Yemen.

The British explorer Wilfred Thesiger, who spent five years in the Empty Quarter (Rub' al Khali) with local Bedouins between 1945 and 1950, described the barren, seldom-changed landscapes the Romans would have come close to.

“Passing generations have left fire-blackened stones at camping sites, a few faint tracks polished on the gravel plains. Elsewhere the winds wipe out their footprints,” he writes in his 1959 book Arabian Sands.

The Roman and auxiliary army proceeded from Al Jawf to al-Bayda (formerly “Asca”). They took control of the city, advanced to Baraqish (formerly “Athrula” or “Yathill”) and secured the area, leaving a garrison and provisions there for their rear. Next, they marched on to the large, populous oasis of Marib and besieged the city in the hope of breaking its defences. Marib must have felt like the final prize in a relatively easy campaign.

However, Strabo says that the Romans allegedly ran out of water before they could even enter the city and take a glance at the well-irrigated gardens of the Sabaeans. They had used up most of their supplies and energy. Though close to the high city walls of Marib, Aelius Gallus realised he could go no further. To avoid a worse predicament, he turned his army back to Alexandria. It is said that he lost more of his men to exhaustion, hunger, sunstroke and disease than direct combat.

Roman literary sources tried to assign blame for the debacle on “treacherous” Nabatean allies who misled them in their advance. In hindsight, it’s easy to see why the expedition was ill-fated and ill-conceived from the start: the Romans didn’t know much about the people they wanted to conquer. Roman geography and exploration, beyond the Mediterranean world, coastal lands and main trade routes, was still in its relative infancy.

The expedition to Marib is a story passed down to us from Roman sources, save for a fragmentary, recently analysed Sabaean inscription found at the Awam temple, which may shed light on the political landscape in the ancient kingdoms of Yemen more than they do on the interaction with Aelius Gallus’s army, as noted (in French) by Arbach and Schiettecatte in their 2017 paper retracing the expedition. We regrettably lack more.

Experts disagree on the consequences of the Roman expedition to Marib. Some say it was insignificant, some that it precipitated the fall of several city-states in Al Jawf.

For Rome, the expedition enabled a more accurate mapping of the region. Maritime traffic increased between Roman Egypt, East Africa and India as seafarers working the spice route acquainted themselves with the monsoon winds and increasingly bypassed southern Arabia, which they no longer needed and which was perhaps precisely motivated to mitigate in part the impact of their crushing defeat.

While the Romans tightened their grip on other parts of Arabia (Syria had already been annexed as a Roman province and the Nabatean Kingdom would follow suit at the turn of 2nd century CE), they never set foot in its southern part again, except for occasional trade or the exchange of envoys.

The great dams of Marib

What would the Romans have seen? Despite ancient Marib’s prime days waning by 500 BCE, “Marib continued to be an important centre and was located in the middle of the largest oasis in the region, which could be irrigated with the help of the famous dams,” says Holger Hitgen from the German Archaeological Institute, who left Yemen in 2013 after two decades.

The Great Marib Dam was an engineering marvel and already constructed 700 years before the Roman arrival. Sophisticated and imposing, it collected rainwater to irrigate a large agricultural area supplementing the monsoon rains. The dam lasted well into the Christian era before it collapsed in the 7th century CE. The neighboring kingdom of Himyar expanded and ultimately overtook Marib and the Sabaean state.

The six pillars of the Barran temple featured on national post stamps and were to be the flag emblem of the new Saba region, under the federal plan discussed at the National Dialogue Conference following the 2011 revolution.

It’s tempting to establish filiation between ancient and modern times, yet displacement and amalgamation have often blurred narratives. Recently, the Hollywood-production-worthy Egyptian Golden Pharaoh Parade held in Cairo underlined the risk of ancient history being a vector of nationalism to distract from contemporary socioeconomic woes.

Nonetheless, the Sabaeans and the Roman defeat recall the possibility of prosperous times for Yemenis facing a multitude of hardships and for Maribis concerned for their immediate safety. “This is a society that takes pride in that it was once a civilisation,” says Nadwa al-Dawsari.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.