British empire: The forgotten Victorian crusade to colonise Palestine

I was deeply dismayed, yet not surprised, to learn that British Prime Minister Liz Truss was considering following Donald Trump’s lead and moving Britain’s embassy in Israel from its current location in Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

Dismayed, because the move would signify to Palestinians that the British government cares nothing for their rights to freedom, self-determination and equality.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

On the day the US embassy opened in Jerusalem in May 2018, 59 Palestinians were killed by the Israeli military along the fence of the world’s largest open-air prison, the Gaza Strip, in what Amnesty International called “a horrifying example of use of excessive force and live ammunition against protesters who did not pose an imminent threat to life”.

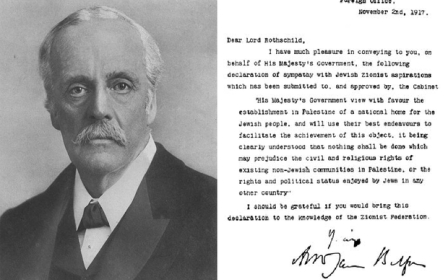

What responsible government would risk reopening these wounds? Yet I am not surprised, for such behaviour, unfortunately, has a long chain of precedents. In the Balfour Declaration of 1917, Britain promised Palestine, with an almost 90 percent Arab Muslim and Christian population, as a Jewish homeland.

Over 30 years, Britain enforced the Balfour Declaration’s implications, its heavy-handed repression of the Arab Revolt of 1936–39 leaving Palestinian society broken and demoralised.

After the November 1947 UN vote to partition Palestine, British soldiers did nothing as residents of Haifa and Jaffa were forced from their homes by the Haganah, the forerunner of the Israeli army.

Over 700,000 refugees were driven into exile where their seven million descendants remain, an injustice which remains at the heart of the conflict. The tragedy of Palestine thus deserves to be viewed among the malign legacies of British colonialism.

Holy real estate

Britain’s disastrous dalliance in Palestine in fact stretches back much further, into the 19th century. In researching my new book, Palestine in the Victorian Age, I uncovered some of this largely forgotten history, the backdrop not only to the brutality and blundering of the Mandate period, but also to Britain’s contemporary complicity in Palestinian suffering.

The Bible made the Victorians view Palestine somewhat differently from other parts of the globe they eyed for colonisation. Palestine - part of the ailing Ottoman Empire, the “sick man of Europe” - was not only considered real estate, but holy real estate.

In the early 19th century, Britain was in the grip of the Evangelical Revival, a fundamentalist brand of Protestantism which emphasised the “Restoration” of the world’s Jewish population to Palestine, a notion today closely associated with pro-Israel American Evangelicals.

The Bible made the Victorians view Palestine somewhat differently from other parts of the globe they eyed for colonisation

With the British imperial hegemony of the Victorian period, many in Britain came to believe it was their country’s destiny to achieve this goal, regardless of Palestine’s indigenous Arab population.

It was an American, Connecticut-born Edward Robinson (his Puritan forefathers had departed England in the 17th century), who initiated the Victorians’ craze for Palestine.

Where previous European travellers and pilgrims had paid reverent visits to ancient Christian sites such as Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Robinson scorned them, and even denied that the paramount Christian site in Jerusalem marked the real spot of Christ’s crucifixion.

Yet Robinson’s 1841 Biblical Researches in Palestine, a bestseller in Europe and America, would set tens of thousands of western travellers following in his footsteps.

This phenomenon, which became known as the “Peaceful Crusade”, included missionaries, archaeologists and artists, but also upper-class tourists, especially after the Leicester-based Baptist preacher Thomas Cook began offering tours to Palestine and Egypt in the 1860s.

'Brute beasts'

While Robinson had expressed some sympathy with Palestinians, dutifully recording the hospitality they offered him, others would not be so appreciative of Palestine’s indigenous society.

In starkly racist language, Claude Reignier Conder - a British officer who conducted an archaeological survey of Palestine in the 1870s - described the people he encountered as “very little better than brute beasts”.

Conder later became a patron of Zionist groups in London, noting that if Palestine was colonised and farmed according to European methods, it “may become a very important source of corn supply for England”.

Such colonial attitudes would prefigure practical plans for settler colonisation in Palestine. Such schemes, which predated the emergence of Jewish groups advocating emigration to Palestine in the 1880s, had little to do with genuine solidarity with the oppression Jews were suffering in the murderous pogroms then taking place in the Russian empire.

'Overcrowded London'

In 1882, Elizabeth Anne Finn, the widow of Britain’s former consul in Jerusalem, founded the Syrian Colonisation Fund, which sent Jews to work in often inhospitable conditions in Cyprus, Syria and Palestine.

“This society helps refugees to leave England in search of new homes,” Finn wrote in a newspaper, beseeching funds to help relieve what she called “the congestion and anxiety here in overcrowded London” by ensuring refugees ended up in Palestine rather than Britain.

The British name which became most closely associated with settler colonialism in Palestine, decades before Theodor Herzl authored his treatise The Jewish State, was that of Laurence Oliphant.

An aristocrat who was a personal friend of Queen Victoria, Oliphant achieved fame as a traveller, novelist and parliamentarian before he took an interest in Palestine in the late 1870s.

Oliphant visited Palestine in 1879, looking for an area to establish a large Jewish colony. Forced to admit that the fertile land in Palestine west of the River Jordan was “already under cultivation by the resident [Arab] population”, he instead looked east to present-day Jordan, where he identified an area of land of 1.5m acres.

Yet this area, too, was populated, especially by Bedouin tribes. Oliphant recommended their ethnic cleansing from the area, believing that “there would be no difficulty in clearing them out”.

When his plan failed, he settled near Haifa, devoting the rest of his life to aiding the early Zionist settlers.

The crimes of British rule in Palestine from 1917 to 1948 were built on these colonial foundations, and subsequent British policies have merely engrained the injustice.

Today’s politicians have the choice to begin to atone for almost two centuries of Britain’s meddling in the region, by adopting a policy that prioritises human rights, dignity and freedom. It is a stain on our country’s conscience that its politicians continue to move in the wrong direction.

Palestine in the Victorian Age: Colonial Encounters in the Holy Land, by Gabriel Polley, is published by Bloomsbury.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.